| Cardiology Research, ISSN 1923-2829 print, 1923-2837 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cardiol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 16, Number 6, December 2025, pages 533-540

Analysis of Acute Myocardial Infarction Mortality Trends in the African American Population in the United States (1999 - 2020)

Muhammad Umer Riaz Gondala, f , Luke Rovenstineb, Fawwad Alamc, Mohammad Baiga, Nana Kwasi Appiaha, Ayushma Acharyaa, Fatima Khalida, Haider Khana, Pallab Sarkera, Zainab Kiyanid, Toqeer Khane, Syed Jaleela

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Tower Health, Reading Hospital, West Reading, PA, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, Drexel University, West Reading, PA, USA

cDepartment of Internal Medicine, Piedmont Athens Regional, Athens, GA, USA

dDepartment of Internal Medicine, Islamabad Medical and Dental Center, Islamabad, Pakistan

eDepartment of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA

fCorresponding Author: Muhammad Umer Riaz Gondal, Department of Internal Medicine, Tower Health, Reading Hospital, West Reading, PA, USA

Manuscript submitted April 29, 2025, accepted September 22, 2025, published online December 20, 2025

Short title: Analysis of AMI Mortality Trends

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cr2082

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) remains a leading cause of mortality in the African American population, warranting an examination of regional and demographic trends to inform health policies.

Methods: Utilizing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s WONDER death certificate database, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of AMI mortality from 1999 to 2020 in African Americans and overall adults aged 25 and older. Age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) per 100,000 persons were calculated and stratified by year, sex, race, and geographic region. Joinpoint regression facilitated the assessment of mortality trends, revealing average annual percentage changes (AAPCs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results: Over the study period (1999 - 2020), there were 3,015,339 total deaths due to AMI in adults aged 25 and older. African Americans had the highest AAMR, at 71.5, followed by Whites, at 63.5, and the lowest among Asians, at 32.6. Overall, AAMR decreased in the African American population from 128.5 in 1999 to 48.5 in 2020, with an AAPC of -5.29 (95% CI: -5.69 to -4.9). AAMR decreased from 109 in 1999 to 37.6 in 2020 in African American females. African American males experienced a decline from 157.8 to 63.4 in AAMR. African American males had a higher overall AAMR (88.6) than females (59.3). Regionally, AAMR was highest in the South (77.6) and lowest in the Northeast (57.6) among African Americans.

Conclusions: While AMI mortality has declined, persistent differences persist in the African American community. African American males experience a higher mortality rate as compared to females. Regional variations, notably the higher AAMR in the Southern region, emphasize the need for targeted health policies to mitigate disparities and enhance healthcare access. These measures may include expanding insurance coverage and improving access to healthcare, education, food, and employment for African Americans.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction; African Americans; Mortality trends

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States [1], affecting men, women, and people of most ethnic and racial backgrounds. In 2021, heart disease contributed to 695,000 deaths in the United States, accounting for one in every five deaths [2]. Among African Americans, heart disease remains the leading cause of death, contributing to 22.6% of all deaths - a higher proportion than all other ethnicities [1]. As the prevalence of risk factors for heart disease, including hypertension, diabetes, and obesity, continues to increase, heart disease will likely continue to remain a significant burden for morbidity and mortality, especially in African Americans. With recent advancements in management and prevention, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) mortality continues to decrease. However, persistent socioeconomic and chronic health disparities continue to exist within the African American population, such as limited access to health insurance, both private and Medicaid, and higher rates of heart disease and stroke (20% and 40% higher, respectively) [3].

In this study, we add to what is known about how African Americans are disproportionately affected by chronic health problems. However, this study uniquely evaluates AMI-related mortality amongst African American subgroups and the social determinants of health that contribute to their disposition, so that future policy measures may be enacted for health equality to be achieved in the United States.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC WONDER) was used to identify AMI-related deaths occurring in the United States. Data from the Underlying Cause of Death Public Use Record and CDC WONDER death certificates were analyzed to determine AMI as the underlying cause of death among African Americans. International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification codes for AMI were utilized: I21.0, I21.1, I21.2, I21.3, I21.4, and I21.9.

Adults aged 25 and older were included in the analysis at the time of death. AMI-related deaths were extracted from January 1999 to December 2020. Race and ethnicity groups were defined as African American, White, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, or Pacific Islander. These are self-identified. Regions were classified into Northeast, West, Midwest, and South according to the Census Bureau definition. Location of death included medical facilities (outpatient, inpatient, emergency department, dead on arrival or status unknown), decedent’s home, hospice facility, and nursing or long-care homes.

The CDC WONDER database classifies “African Americans” under the broader category of “Black or African American” and adheres to federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) standards, typically based on self-identification and a bridged-race methodology that standardizes different reporting categories for statistical purposes. Within the database, data can be filtered by single or multiple race categories, including “Black or African American only.”

The 2013 National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme was utilized to divide the population into metropolitan and non-metropolitan for urban-rural classifications. Metropolitan included large central metro (counties with a population of > 1 million), large fringe metro (counties with > 1 million population not qualifying as large central metro counties), medium metro (250,000 to 999,999), and small metro (< 250,000). Non-metropolitan included micropolitan (10,000 to 49,999) and noncore (< 10,000).

AMI-related crude and age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) per 100,000 were determined. Crude mortality rates were determined by dividing the number of AMI-related deaths by the corresponding US population of that year. AAMRs were calculated by standardizing the AMI-related deaths to the 2000 US population.

The Joinpoint Regression Program version 5.0.2 was used to determine trends in AAMR using annual percentage change (APC). This method identifies significant changes in AAMR over time by fitting log-linear regression models where temporal variation occurred. The Monte Carlo permutation test calculated APCs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the AAMR at the identified line segments linking join points. The weighted average of the APCs was calculated and reported as AAPCs, and the corresponding 95% CIs were reported as a summary of the reported mortality trend for the entire study period. APCs and AAPCs were considered to increase or decrease if the slope describing the change in mortality significantly differed from 0 using two-tailed t-tests. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

Ethical compliance and institutional review board (IRB) approval were not applicable to this study.

| Results | ▴Top |

Over the study period (1999 - 2020), there were 3,015,339 total deaths due to AMI in adults aged 25 and older, with 317,504 occurring among African Americans, accounting for 10.5% of total deaths. Total deaths over the study period from 1999 to 2020 were highest among Whites (2,625,748, 87% of total deaths).

Among African Americans, 36% of deaths occurred in the inpatient setting, 23.9% in outpatient/emergency room (ER), 22.5% in the decedent’s home, 11.3% in a nursing home, and 2.2% were declared dead on arrival at a hospital.

African Americans had the highest overall AAMR at 71.5 deaths per 100,000 (95% CI: 71.2 to 71.7), followed by Whites at 63.5 deaths per 100,000 (95% CI: 63.5 to 63.6) and American Indian or Alaskan Native at 42.2 deaths per 100,000 (95% CI: 41.5 to 43.0). The lowest rates were observed in Asian or Pacific Islanders, at 32.6 (95% CI: 32.3 to 32.9), as shown in Figure 1.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) in the overall population and amongst races. |

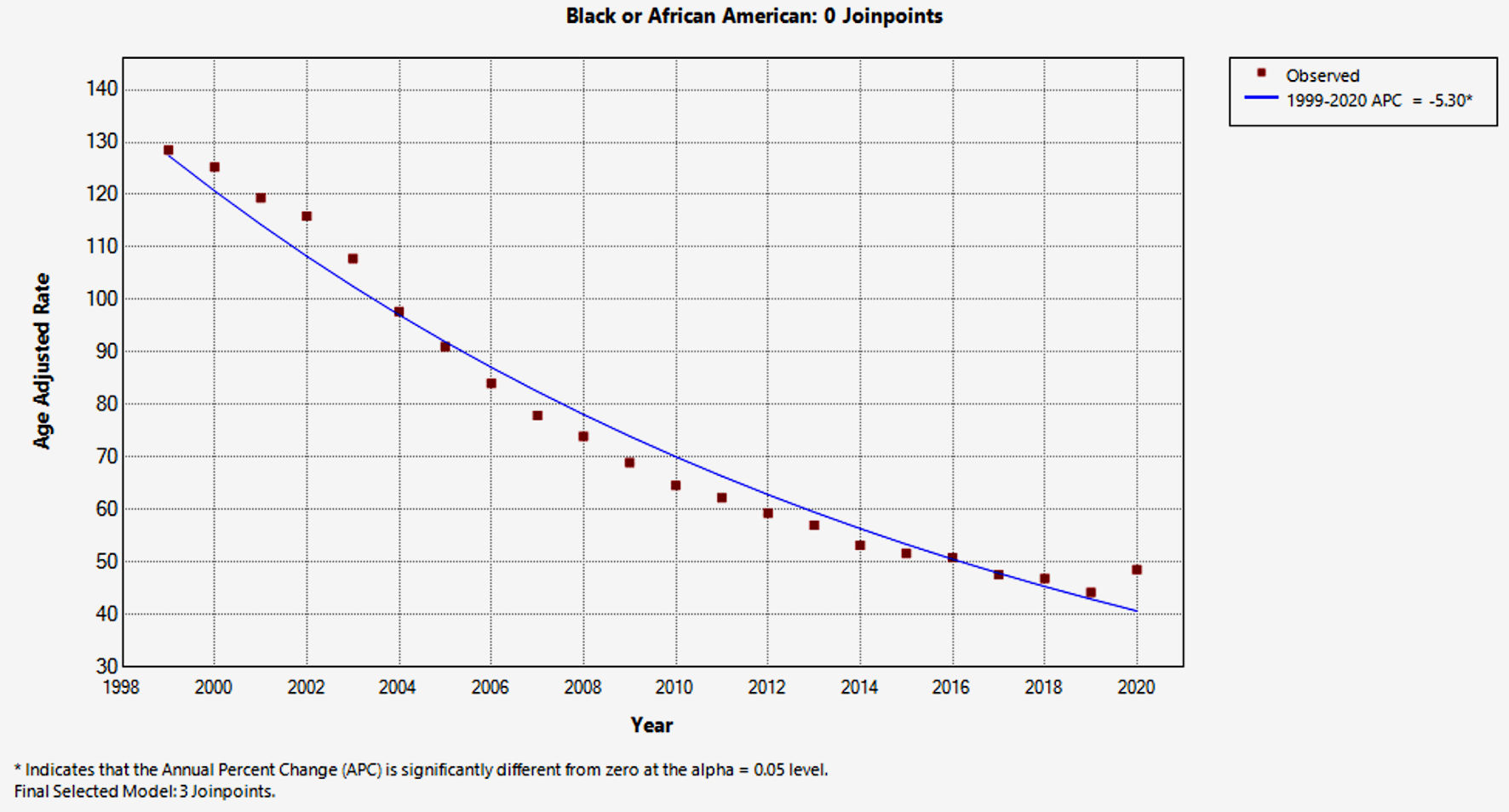

Overall, AAMR decreased in the African American population from 128.5 deaths/100,000 in 1999 to 48.5 deaths/100,000 in 2020, with an average annual percent change (AAPC) of -5.29 (95 % CI: -5.69 to -4.9), as seen in Figure 2.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Age-adjusted mortality rates with annual percentage change in African Americans. |

In Whites, the AAMR decreased from 113 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 112.4 to 113.5) in 1999 to 40.7 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 40.4 to 40.9) in 2020. American Indians had an AAMR of 85.6 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 78.7 to 92.5) in 1999, which decreased to 29.0 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 26.8 to 31.2). In Asians, the AAMR decreased from 63.2 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 60.6 to 65.9) in 1999 to 24.7 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 23.9 to 25.5).

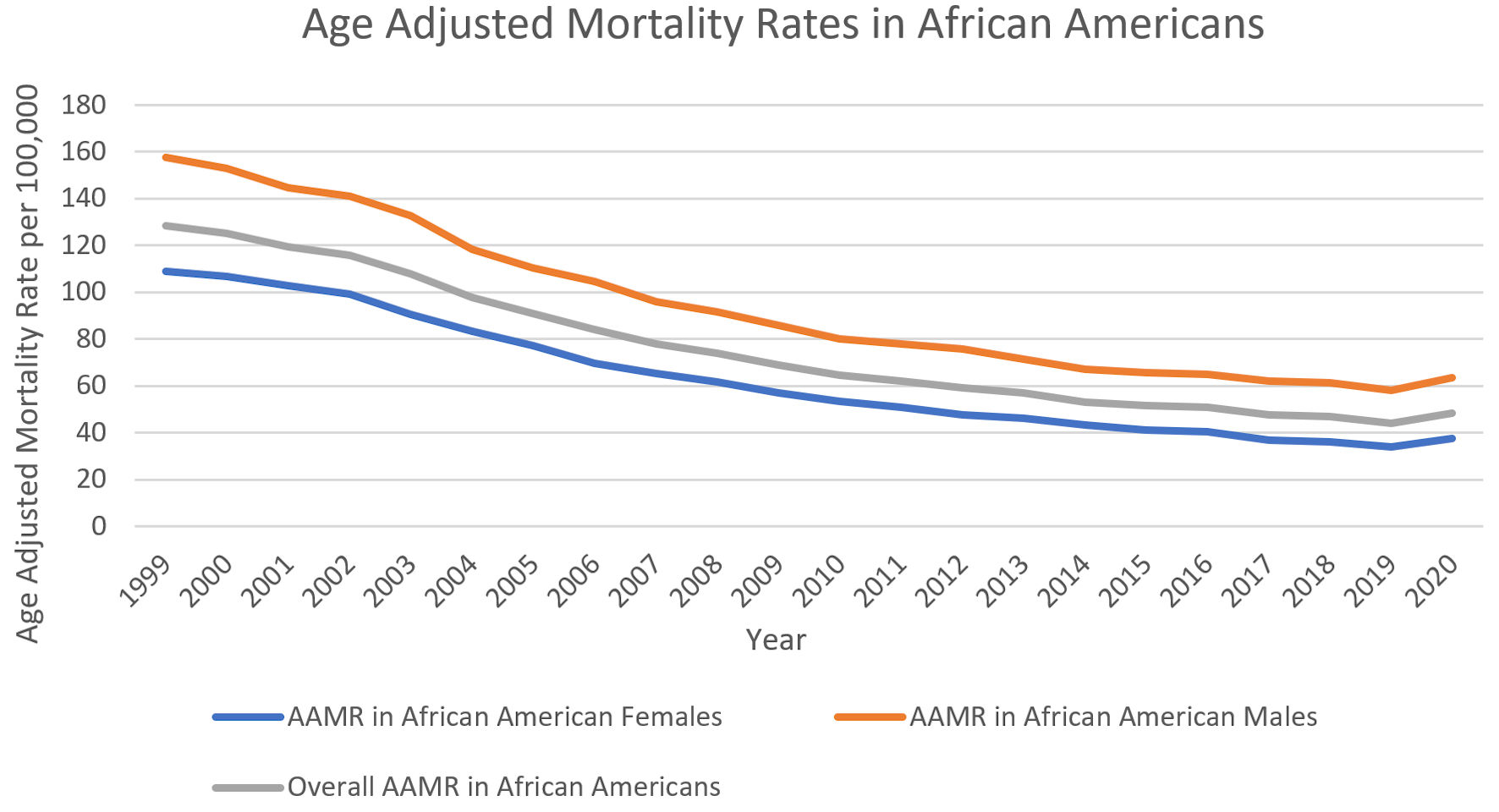

African American males had a higher overall AAMR of 88.6 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 88.1 to 89.0), a rate that was almost 1.5 times higher than that of females, who had an AAMR or 59.3 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 59.0 to 59.6).

In African American females, AAMR decreased from 109 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 106.8 to 111.1) in 1999 to 37.6 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 36.6 to 38.5) in 2020, with an AAPC of -5.85% (95% CI: 6.23 to -5.83), as seen in Figure 3. The AAPC was -3.45 (95% CI: -4.97 to -1.06) from 1999 to 2020, which then increased to -7.97 (95% CI: -9.74 to -7.3), decreased to -5.17 (95% CI: -5.78 to -4.60 ), and finally further reduced to 2.01 (95% CI: -2.02 to 4.21).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) in African Americans. |

African American males experienced a decline from 157.8 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 154.4 to 161.2) to 63.4 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 61.9 to 64.9) in AAMR, with an AAPC of -4.95 (95% CI: -5.37 to -4.51) as seen in Figure 3. The AAPC was -3.96 (95% CI: -5.64 to -1.12), which increased to -7.06 (95% CI: -9.13 to -6.44), subsequently decreased to -3.74 (95% CI: -4.97 to -3.08), and then further reduced to 2.24 (95% CI: -1.90 to 4.48).

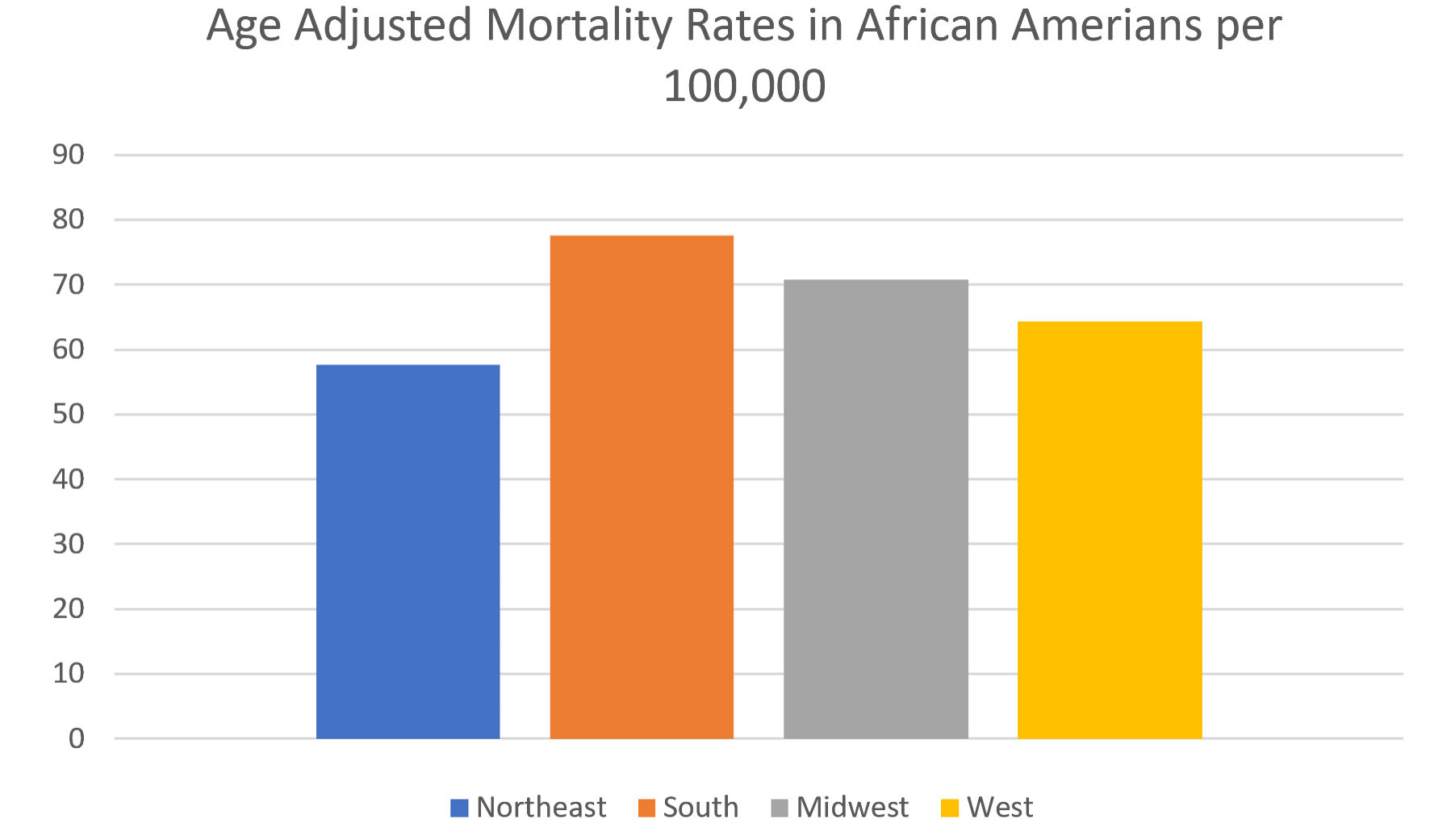

Among African Americans, AAMR was highest in the Southern United States at 77.6 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 77.3 to 78.0), then Midwest 70.8 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 70.2 to 71.4), West 64.3 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 63.5 to 65.1), and lowest in the Northeast 57.6 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 57.1 to 58.1), as seen in Figure 4. The top five states with the highest AAMR among its African Americans were Arkansas at 178.7 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 174.9 to 182.4), followed by Mississippi with 122.9 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 120.9 to 124.9), Kentucky with 104.3 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 100.9 to 107.6), Tennessee 102.2 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 100.3 to 104.2), and Missouri 100.2 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 98.0 to 102.5). The lowest AAMR was in Minnesota at 20.9 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 18.5 to 23.3); Alaska, 21.6 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 14.9 to 30.3); and Hawaii at 21.8 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 15.3 to 30.2). There were a few states with meager crude rates where AAMR was unreliable.

Click for large image | Figure 4. Age-adjusted mortality rates among African Americans in different regions in the United States. |

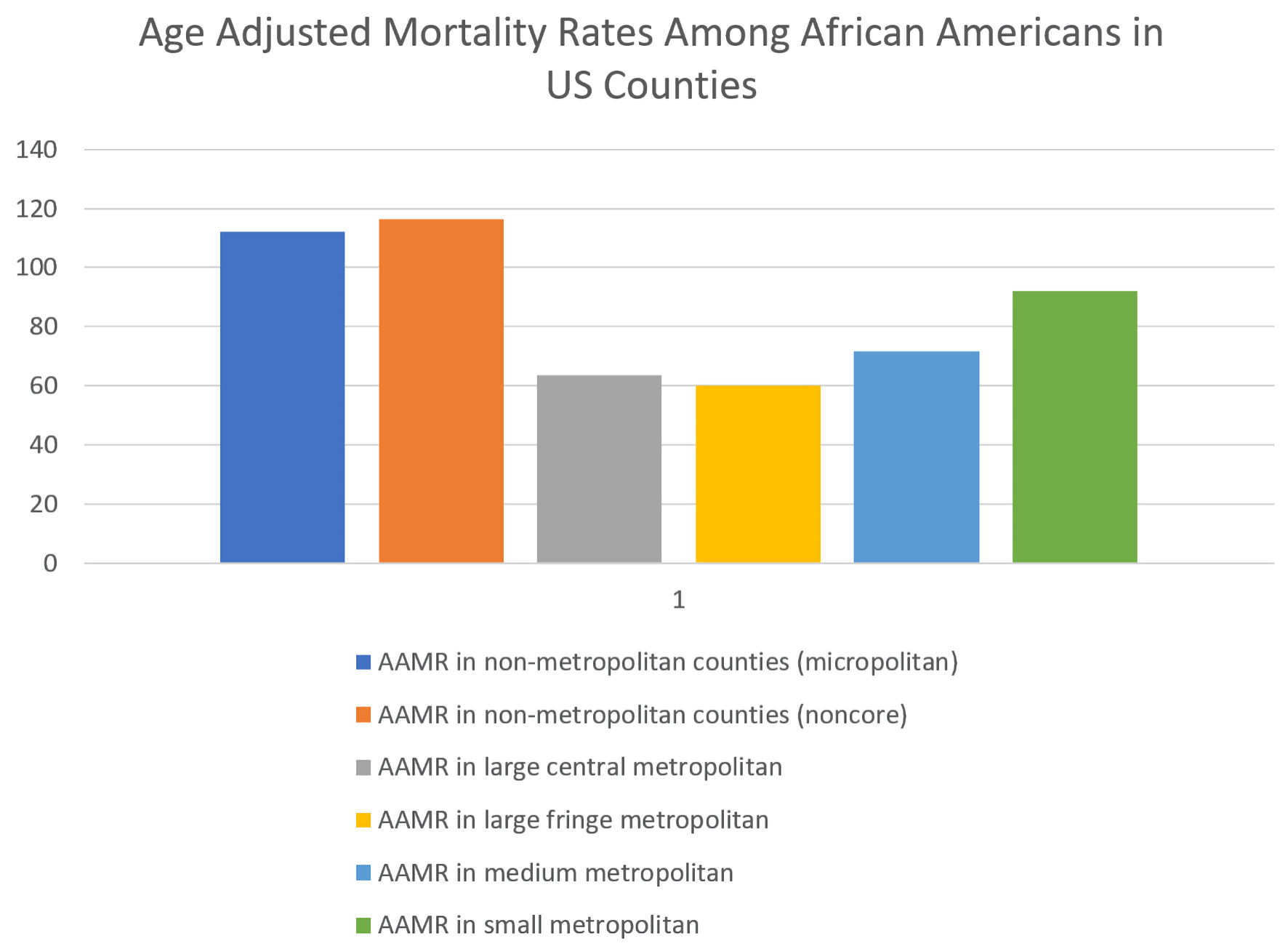

In African Americans, AAMR was higher in non-metropolitan counties, with 112.1 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 110.8 to 113.4) in micropolitan and 116.4 in non-core (95% CI: 115.1 to 117.8). Among metropolitan populations, small metropolitan communities had death rates among their African American communities of 92.0 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 90.8 to 93.1), compared to medium metropolitan communities of 71.7 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 71.1 to 72.3), with large central metropolitan communities of 63.6 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 63.2 to 64.0). Rates were lowest in large fringe metropolitan areas at 60.0 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 59.5 to 60.5), as seen in Figure 5. AAMR was almost twice as high in non-core counties as in large fringe metropolitan areas.

Click for large image | Figure 5. Age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) among African Americans in US counties. |

Crude rates of death for each age group declined over the two decades of the study for all groups. African Americans older than 85 had the highest crude mortality rate, which declined markedly from 1318.8 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 1278.6 to 1358.9) to 424.5 deaths/100,000 (95% CI: 407.3 to 441.7), at an AAPC of -6.14 (95 % CI: - 6.51 to - 5.81). All other age groups experienced decreases in mortality. However, those aged 25-34 had the most minor reduction in mortality with an AAPC of -1.34 (95 % CI: -2.06 to -0.47), followed by those aged 35-44 with an AAPC of -2.29 (95 % -2.97 to -1.65).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Over the past two decades, the mortality rate of AMIs has significantly decreased across all epidemiological categories. Essentially, this is attributable to an advancement in managing and preventing ischemic heart disease, reduced time-to-intervention, and the sophistication of how percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is balanced with medical therapy. Using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, Ahuja et al demonstrated that from 2002 to 2016, PCI utilization increased while ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) admissions decreased, resulting reduced mortality [4]. In the past two decades, goal-directed medical therapy (GDMT) has evolved to include more medications, such as cardioselective beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, and gastrin-like protein-1 (GLP-1) agonists, preventing detrimental patient outcomes in those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction [5].

Our study reveals significant findings regarding AMI-related mortality among African Americans between the years 1999 and 2020. Consistent with national trends, AMI mortality rates in the African American population declined. However, despite the downward trend, African Americans had the highest AAMR, followed by Whites (71.5% to 63.5%) and then American Indian or Alaskan Native, 42.2 (95% CI: 41.5 to 43.0). This may be caused by limited access to medical care, which impacts this population. In healthcare settings, African Americans are more likely to be treated at smaller, underfunded hospitals compared to their White counterparts [6]. They are more likely to be uninsured and have little money to afford ongoing treatment or expensive interventions, such as GDMT or outpatient PCI [7]. Limited access to transportation restricts access to doctor appointments, and the quality of care is often compromised. A high incarceration rate in African American males (five to six times higher than Whites) also contributes to less income within a household, an interruption in standard medical care, and exacerbation of cardiovascular risk factors leading to future detriment [8].

Our observations also revealed that African Americans older than 85 showed the most substantial decrease in AAPC in mortality; however, those aged 25 - 34 showed the least reduction (-6.14 vs. -1.34). Elderly patients are more likely to experience several comorbidities that complicate disease presentation and management. Furthermore, these patients may present to the hospital after more extended periods, decreasing the likelihood of receiving interventional treatment and increasing mortality [9, 10]. Between African American males and females, the AAPC was lower in males at -4.95% compared to females at -5.85%. The AAMR of African American was nearly 1.5 times higher in men than in women, at 88.6 and 37.6, respectively. These findings may be plausible explanations for the social determinants of health and systemic differences within the African American population. It has been demonstrated that economic and social conditions account for 36% of the variation in cardiovascular disease (CVD) between population groups [11]. Several socioeconomic factors that may impact the African American population include a higher rate of poverty and food insecurity. African Americans are also disproportionately affected by hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity, all significant risk factors for CVD, and negatively influenced by food insecurity [12-14]. Further, African Americans are more likely to live with chronic stress due to social and environmental stressors such as pollution and gentrification [6, 15].

The results of this study indicate that geographical differences persisted for the entire population. African American AAMR was higher in rural versus urban settings (112.1 vs. 63.6) and in the Southern United States (77.6 vs. 57.6 in the Northeast), with variation between states. It has been shown that income and cardiovascular mortality are inversely proportional, revealing the disadvantage that African Americans have even before CVD is present [16]. Mortality is higher in segregated communities, which exist in both urban and rural settings [17]. This finding is consistent with the study’s data, which show consistently higher AAMRs among African Americans across both rural and urban settings. Further, in both segregated rural and urban settings, African Americans will have less access to food, education, reliable housing, and employment. These factors promote poor health and predispose an individual to adverse outcomes and unhealthy lifestyles, which place them at risk for CVD. Chang et al identified a strong correlation between food insecurity and CVD, noting significantly higher prevalence rates among CVD patients. The authors attribute the disproportionate burden of CVD and its risk factors in racial and ethnic minority populations to structural determinants of health. These include socioeconomic and educational disparities, discrimination within healthcare systems, and historical racist policies like redlining, which entrenched housing segregation and systemic inequality for African American and other minority groups. Chang et al mentioned that food insecurity is considerably higher in African Americans [18].

Consistent with this is the fact that African Americans have higher rates of hypertension-related deaths than any other race. An underrepresentation in hypertensive medication trials may further explain this inequality [12].

Considering the implications of these issues for the data in this study, healthcare workers, administrators, and the general public should be encouraged to focus on policies that address these concerns. Implementing new national or statewide policies may help address these current issues. Racial disparity in medical providers is also a possible contributor to this problem. In US hospitals, 5.7% of physicians are Black or African American, while 63.9% are White. With the disproportionate number of Black or African American providers, the implicit bias of those who are in the majority may influence both acute and long-term treatment decisions for African American patients [19]. Although all physicians take a form of the Hippocratic Oath, which states that one must care for all individuals, implicit bias is possible. Cooper et al reported that providers who were pro-White on the Implicit Association Test (IAT) were positively correlated with Black patients, stating they felt as if communication and quality of care were poor [20]. Similarly, Green et al found that providers who had strong implicit bias were less likely to provide treatment for acute coronary syndrome [21]. Other studies have found that Black individuals are less likely to receive appropriate interventions compared to other races [22]. Training providers and healthcare workers on implicit bias may alleviate errors in how African Americans are treated within the hospital. In the same light, increasing African Americans’ access to healthcare, education, and employment may alleviate various social determinants of health that contribute to CVD and AMI mortality. Prospective studies are needed to evaluate whether measures such as the Affordable Care Act - which aims to increase access to affordable health insurance, improving the quality of care, and lowering overall healthcare costs in the United States - have actually decreased mortality. States should aim to increase funding to enhance healthcare access to marginalized communities and offer incentives to increase the number of primary care physicians.

Limitations

This study is subject to several significant limitations inherent to its data source, the CDC WONDER database. First, the findings may be influenced by potential misclassification, as the database is derived from death certificates, which can contain inaccuracies. Second, the analysis is constrained by the limited data on social determinants of health, which are critical factors known to influence mortality rates across different demographic groups. The CDC database does not allow for stratification based on socioeconomic status. A further limitation is that the data depends upon self-identification of race, which may introduce variability. Finally, a limitation exists regarding geographic data, as the database records the state where a death occurred rather than the patient’s residence. Consequently, for individuals who migrated during the study period, their original place of residence is not captured, which could skew state-specific findings.

Learning points

From 1999 to 2020, AMI mortality decreased amongst all racial groups; however, African Americans continue to have higher mortality compared to other groups.

Among African Americans, AMI mortality is higher in males and in the Southern region of the United States.

AMI mortality is higher in African Americans in non-metropolitan counties compared with those in metropolitan areas.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Muhammad Umer Riaz Gondal: writing - original draft, writing - review and editing, conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, visualization. Luke Rovenstine: writing - original draft, writing - review and editing, conceptualization. Fawwad Alam: investigation, formal analysis, methodology. Mohammad Baig: investigation, formal analysis, methodology. Nana Kwasi Appiah: investigation, formal analysis, methodology. Ayushma Acharya: investigation, formal analysis, methodology. Fatima Khalid: resources, visualization. Haider Khan: resources, visualization. Pallab Sarker: resources, visualization. Zainab Kiyani: project administration, resources, visualization, validation. Toqeer Khan: resources, visualization. Syed Jaleel: supervision.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause of Death 2018-2021 on CDC WONDER Database [Internet]. [cited Feb 2, 2023].

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, Baker-Smith CM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;147(8):e93-e621.

doi pubmed - Health, United States, 2016: with chartbook on long-term trends in health. Hyattsville (MD). 2017.

pubmed - Ahuja KR, Saad AM, Nazir S, Ariss RW, Shekhar S, Isogai T, Kassis N, et al. Trends in clinical characteristics and outcomes in ST-elevation myocardial infarction hospitalizations in the United States, 2002-2016. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2022;47(12):101005.

doi pubmed - Sharma A, Verma S, Bhatt DL, Connelly KA, Swiggum E, Vaduganathan M, Zieroth S, et al. Optimizing foundational therapies in patients with HFrEF: How do we translate these findings into clinical care? JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2022;7(5):504-517.

doi pubmed - Brewer LC, Cooper LA. Race, discrimination, and cardiovascular disease. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(6):455-460.

pubmed - Jha AK, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Low-quality, high-cost hospitals, mainly in South, care for sharply higher shares of elderly black, Hispanic, and medicaid patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(10):1904-1911.

doi pubmed - Wang EA, Redmond N, Dennison Himmelfarb CR, Pettit B, Stern M, Chen J, Shero S, et al. Cardiovascular disease in incarcerated populations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(24):2967-2976.

doi pubmed - Forman DE, Chen AY, Wiviott SD, Wang TY, Magid DJ, Alexander KP. Comparison of outcomes in patients aged <75, 75 to 84, and >/= 85 years with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (from the ACTION Registry-GWTG). Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(10):1382-1388.

doi pubmed - Brieger D, Eagle KA, Goodman SG, Steg PG, Budaj A, White K, Montalescot G, et al. Acute coronary syndromes without chest pain, an underdiagnosed and undertreated high-risk group: insights from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Chest. 2004;126(2):461-469.

doi pubmed - Patel SA, Ali MK, Narayan KM, Mehta NK. County-level variation in cardiovascular disease mortality in the United States in 2009-2013: comparative assessment of contributing factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184(12):933-942.

doi pubmed - Gu A, Yue Y, Desai RP, Argulian E. Racial and ethnic differences in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among US adults with hypertension: the national health and nutrition examination survey, 2003 to 2012. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(1).

doi pubmed - Shai I, Jiang R, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Hu FB. Ethnicity, obesity, and risk of type 2 diabetes in women: a 20-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(7):1585-1590.

doi pubmed - Raisi-Estabragh Z, Kobo O, Mieres JH, Bullock-Palmer RP, Van Spall HGC, Breathett K, Mamas MA. Racial disparities in obesity-related cardiovascular mortality in the United States: temporal trends from 1999 to 2020. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(18):e028409.

doi pubmed - Brook RD, Franklin B, Cascio W, Hong Y, Howard G, Lipsett M, Luepker R, et al. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;109(21):2655-2671.

doi pubmed - Machado S, Sumarsono A, Vaduganathan M. Midlife wealth mobility and long-term cardiovascular health. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(10):1152-1160.

doi pubmed - Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404-416.

doi pubmed - Chang R, Javed Z, Taha M, Yahya T, Valero-Elizondo J, Brandt EJ, Cainzos-Achirica M, et al. Food insecurity and cardiovascular disease: current trends and future directions. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2022;9:100303.

doi pubmed - Patrick B. "What’s your specialty? New data show the choices of America’s doctors by gender, race, and age." Association of American Medical Colleges, Jan. 12, 2023. www.aamc.org/news/what-s-your-specialty-new-data-show-choices-america-s-doctors-gender-race-and-age.

- Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, Beach MC, Sabin JA, Greenwald AG, Inui TS. The associations of clinicians' implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):979-987.

doi pubmed - Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, Ngo LH, Raymond KL, Iezzoni LI, Banaji MR. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1231-1238.

doi pubmed - Taylor HA, Jr., Canto JG, Sanderson B, Rogers WJ, Hilbe J. Management and outcomes for black patients with acute myocardial infarction in the reperfusion era. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Investigators. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(9):1019-1023.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cardiology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.