| Cardiology Research, ISSN 1923-2829 print, 1923-2837 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cardiol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cr.elmerpub.com |

Review

Volume 16, Number 6, December 2025, pages 467-474

Stress and Acute Coronary Syndrome

Shereif H. Rezkallaa, d, Robert A. Klonerb, c

aMarshfield Clinic Research Institute, Marshfield, WI, USA

bCardiovascular Research Institute, Huntington Medical Research Institutes, Pasadena, CA, USA

cCardiovascular Division, Department of Medicine, Keck School of Medicine of University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

dCorresponding Author: Shereif H. Rezkalla, Marshfield Clinic Research Institute, Marshfield, WI, USA

Manuscript submitted July 24, 2025, accepted September 5, 2025, published online December 20, 2025

Short title: Stress and Acute Coronary Syndrome

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cr2123

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Mechanisms

- Stress in Laboratory Studies

- Stress in Humans

- Natural Disasters

- Hurricanes and Cardiac Events

- Emotional Stress of Sporting and Cardiovascular Events

- Anger and Emotional Impact

- Snow Shoveling

- Seasonal Variations and Cardiac Events

- Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy

- Conclusions

- References

| Abstract | ▴Top |

A plethora of risk factors, such as hypercholesterolemia, smoking, hypertension, and others lead to the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. Vulnerable plaques are formed, and rupture of such plaques results in the development of myocardial infarction. Great progress has been made in the medical community’s focus on management of risk factors, with clear improvement in the incidence and outcome of myocardial infarction. However, triggers of plaque rupture, which include significant physical and mental stress, need more attention. In this report, we focused on the effect of emotional stress in triggering various acute cardiac events. Natural disasters such as earthquakes result in significant emotional stress, and have been associated with substantial increases in cardiac death and acute myocardial infarction. This is more pronounced with severe events, particularly if they occur in the early morning hours. Anger and severe emotional stress from various life events, particularly from stressed marital relations or stressful working conditions, will result in markedly increased occurrence of myocardial infarction. This is more pronounced in patients with known coronary artery disease or significant risk factors. Providers need to focus on management of stress during hospitalization for myocardial infarction, as well as in the rehabilitation phase of such events.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome; Coronary atherosclerosis; Myocardial infarction; Risk factors; Stress

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Plaque rupture is the major cause of acute myocardial infarction and appears to be the dominant mechanism in at least three-quarters of acute events [1]. A vulnerable plaque is characterized by a large necrotic core, a thin fibrous cap, intra-plaque hemorrhage, and an infiltration of inflammatory cells [2]. A plethora of risk factors, such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking, diabetes, and a variety of genetic predispositions, lead to the development of vascular plaques. Stress, either physical or emotional, is a trigger for acute coronary events, including plaque rupture, with the final development of myocardial infarction and acute coronary syndromes [3]. The purpose of this paper is to describe the types of triggers that have been associated with acute coronary events, with emphasis on triggers that cause acute episodes of psychological and/or physical stress. The papers reviewed were chosen from a literature search performed on PubMed using key terms including “acute cardiac event,” “emotional stress,” “physical stress,” “natural disasters,” and “Takotsubo cardiomyopathy,” and included studies published in peer-reviewed journals. Because of the nature of the events reported, most of these studies do not have a typical control group and are descriptive in nature, and the authors recognize this as a potential limitation. This report will focus on various types of stress and awareness of these triggers, which may help avoid the development of these events, particularly in people who have known coronary artery disease or are vulnerable to the development of coronary atherosclerosis.

| Mechanisms | ▴Top |

How does acute psychologic or physical stress trigger an acute coronary event? When the brain perceives stress, there is a stimulation of the sympathomimetic pathway, leading to the firing of sympathetic nerves, as well as the release of adrenaline (epinephrine), a neurotransmitter and hormone involved in the “fight-or-flight” response. Adrenaline can increase oxygen demand of the heart by increasing heart rate, blood pressure, and contractility. Sympathetic nervous system activation and the release of adrenaline from the adrenal glands prepare the body to respond to stress; however, at the same time, these actions may have deleterious consequences, especially if there are limitations of oxygen delivery due to narrowed blood vessels caused by atherosclerosis. An increased need for oxygen in the setting of reduced supply can lead to myocardial ischemia, myocardial infarction, and ischemia-induced arrhythmias. In addition, sudden increases in blood pressure and cardiac contractility may lead to atherosclerotic plaque fracture. Moreover, overstimulation of the sympathetic nervous system can result in the release of norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter that can induce constriction of blood vessels, further limiting oxygen delivery to vital organs. Sympathetic stimulation can promote platelet production and activation, as well as increase clotting factors, which may further contribute to events such as acute myocardial infarction under stress [4].

It is now well recognized that acute mental stress, such as a standardized public speaking task, can induce a decrease in endothelial function, a decrease in arterial flow-mediated vasodilatation [5]. Those patients who show worsened flow-mediated vasodilatation during mental stress and a greater degree of peripheral vasoconstriction to mental stress are more prone to adverse cardiac events [6, 7]. Impaired microvascular function associated with stress is also prominent in women with no obstructive coronary artery disease [8].

Another reported mechanism for acute coronary syndrome that may involve acute stress is spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD). In a review conducted across 30 medical centers between 2011 and 2017, 83 documented cases of SCAD were reviewed. The SCAD was often associated with physical or emotional stress, particularly in women under 50 years of age. Clinical presentations were mainly myocardial infarction, ventricular arrythmias, and other cardiac events [9]. SCAD can occur spontaneously without obvious triggers or the usual risk factors such as underlying atherosclerosis, but it has been associated with fibromuscular dysplasia and pregnancy. In fact, it is one of the leading causes of myocardial infarction associated with pregnancy. Therapy is variable and may include medical therapy, allowing the dissection to heal, antihypertensive medicines, anti-clotting medicines, and in severe cases, stenting.

Finally, there is increasing evidence that stress (especially chronic stress) stimulates the amygdala of the brain as shown by 18F-fluorodesoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET) imaging. This increased brain activity promotes bone marrow activity leading to leukopoiesis or an increase in immune cells. This increase in immune cell activity then promotes inflammation of the blood vessel walls, contributing to atherosclerosis. Heightened stress-related neural activity was also shown to correlate with vulnerable plaque characteristics and an increase in major cardiovascular adverse events [10]. Higher amygdala activity was also associated with Takotsubo syndrome [11].

| Stress in Laboratory Studies | ▴Top |

A certain breed of apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE-/-) mice are known to have extensive arterial atherosclerosis with development of vulnerable plaques and elevated likelihood of plaque rupture. Roth et al [12] studied 56 mice and observed them for 15 weeks. Mice were divided into a control group or stress group. Stress was achieved with water deprivation, damp bedding, or physical restraints. Mice under stress had more atherosclerotic lesions and more histologic features of vulnerable plaques. This resulted in more cases of myocardial infarction and increased mortality in the stress group. We will review the effect of stress in humans.

| Stress in Humans | ▴Top |

Risk factors such as high cholesterol, hypertension, smoking, diabetes, family history, and others lead to the formation of atherosclerotic arterial plaques - characterized by a large necrotic core, thin capsule, calcification, and acute inflammation - forming vulnerable plaques that, when exposed to triggers, will lead to plaque rupture and the development of acute coronary syndromes [2]. Triggers may be acute, secondary to physical and/or emotional stress, or subacute related to immune or inflammatory response from infection, with the development of coronary events within hours to weeks of the stimulus [13]. This report discusses effects of emotional stress on the triggering of myocardial ischemia and infarction. Patients with known coronary artery disease underwent 48 h of ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring. Mental stress, such as tension, sadness, and frustration, doubled the incidence of coronary ischemia [14]. It also stimulates adrenaline release with increases in heart rate, blood pressure and cardiac contractility. The increase in heart rate and blood pressure increases the double product, and in the setting of reduced coronary flow, results in ischemia. Acute emotional or physical stress may also increase shear stress on the blood vessel wall, putting significant stress on vulnerable plaques, which leads to their rupture and development of acute coronary syndromes [15]. In addition, there is an increase in platelet aggregation and development of coronary spasm, which will potentiate ischemia [16]. Jiang et al [17] conducted a prospective study to investigate the effect of mental stress in patients with documented coronary artery disease. In the study, 125 patients with exercise-induced myocardial ischemia were followed for 5 years. Patients who had mental stress-induced ischemia had significantly higher rates of cardiac events, suggesting that emotional stress is particularly impactful in patients with known coronary artery disease, and this may be related to occurrence of ischemia. Some chest abnormalities such as concave chest may be associated with a lower risk of cardiac event [18], while patients with known significant risk factors are at a greater risk of developing myocardial ischemia. A timed administration of beta-blockers may reduce the effects of stress-induced acute coronary events [19]. We will discuss specific stressful situations and the relationship between these events and the development of acute myocardial infarctions and various acute coronary syndromes.

| Natural Disasters | ▴Top |

Natural disasters present a common situation where stress affects a large community with sudden emotional and physical stress. A common natural disaster that is well studied is a major earthquake resulting in increased cardiac events such as cardiac death and myocardial infarction [20]. A combination of significant physical exertion with intense mental stress, resulting in sudden catecholamine release and increased platelet aggregation will lead to plaque rupture with acute coronary syndromes, which may end with sudden death [19]. Other cardiac events that have been associated with earthquakes include cardiac arrhythmias, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, and pulmonary embolism.

In the summer of 1978, an earthquake measuring 6.4 magnitude on the Richter scale, affected the city of Thessaloniki, Greece. Following the event, there was a significant increase in cardiac death, particularly in patients with underlying atherosclerotic coronary disease [21]. Similar results were noted in the earthquake that hit Armenia in 1988 [22]. Of interest is the increase in the rate of cardiac death for several months following the event. In the great 2011 earthquake of Japan, which was associated with a tsunami and tremendous property damage [23], the increase in cardiac mortality continued for weeks after the event. One of the well-studied events was the Northridge earthquake in Los Angeles, California. In January 1994 at 4:30 am, an earthquake with a magnitude of 6.7 on the Richter scale occurred in Southern California. Being a busy urban area, significant damage occurred, waking people up in the very early morning hours. There was a statistically significant increased risk for cardiac death [24] and myocardial infarction [25]. Most of the cardiac events occurred in people with known coronary artery disease. While most, but not all, earthquakes are associated with increased cardiac events, it seems that the more severe the earthquake, the higher the number of cardiac events. The time of the events also plays a role. In general, the early morning hours represent the period of increased platelet activation and highest rate of myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death [26]. Thus, a strong earthquake that occurs in the early morning hours may be associated with the highest rate of cardiac events.

Other natural disasters such as intense heat waves [27] and blizzards [28], can also lead to intense catecholamine release and trigger acute myocardial infarction [29]. While it is not always possible to predict such disasters, future planning should include adequate cardiac resources to deal with these various cardiac events.

| Hurricanes and Cardiac Events | ▴Top |

Global warming has led to an increase in hurricanes and related events. In the last two decades, the incidence of hurricanes and severe storms has increased by 37% [30]. During such national disasters, there is an increase in the incidence of acute myocardial infarction, cardiac death, and stroke. A unique feature related to hurricanes is that the increase in cardiac events lasts for a prolonged amount of time. Hurricanes lead to significant changes in the community, affecting medical care, health insurance, medication availability, and compliance. During Hurricane Sandy, the increase in cardiac events lasted for 2 weeks [31]. Hurricane Katrina was associated with significant changes in the community, and the increase in cardiac events lasted for up to 6 years [32]. In planning for such disasters, it is essential to plan for appropriate medical resources, particularly for cardiovascular care.

| Emotional Stress of Sporting and Cardiovascular Events | ▴Top |

Major sporting events are usually associated with significant increases in emotional stress among sports fans. Wilbert-Lampen et al [33] examined cardiovascular events in the greater Munich, Germany area during the 2006 Soccer World Cup in June and July, when the German team was playing. There was a significant increase in the number of ST-elevation myocardial infarction, non-ST elevation infarction, and symptomatic arrhythmias during the days of the game compared to a control period. Similar results were reported during Super Bowl games, particularly when the losing team was playing in its hometown [34]. Intense emotional stress associated with an intense catecholamine surge will likely destabilize atherosclerotic plaques [35, 36]. While difficult to control, reasonable precautions may be considered in patients with established coronary artery disease. Patients should be advised to be current in their medications, particularly beta-blockers. They should be advised to avoid active and passive smoking, overeating, high-salt and fatty foods and overexcitement during intense sporting events.

| Anger and Emotional Impact | ▴Top |

In the 1980s, Tofler et al and the MILIS Study Group conducted a multi-center investigation of the limitation of myocardial infarction (MILIS study) [37]. They documented a circadian variation in the occurrence of myocardial infarction, which suggested that infarction is not a random event, but an event that is triggered by some other factors. In a careful history of 849 patients, 18.4% of them had an emotional stress that preceded the onset of the infarction. The emotional stress included emotional upset, lack of sleep, and major surgery, as well as other stressful categories. Years later, a review of 1,623 patients who presented with acute myocardial infarction were interviewed within 4 days of the onset of the event. Of these patients, 2% experienced anger within 2 h of the event, and a total of 8% experienced anger within 24 h of the infarction [38]. Regular use of aspirin and perhaps use of beta-blockers appeared to be protective for the development of myocardial infarction following outbursts of anger. Years later, the same group reported on a similar cohort of 3,886 patients [39]. The incidence of myocardial infarction was more than two-fold higher within 2 h of the onset of an outburst of anger, and the greater the intensity of anger, the higher the risk of developing the infarction. In this report, it was clear that beta-blocker use was associated with lower susceptibility to the development of heart attack. In a review of similar studies, outbursts of anger were associated with increased incidence of myocardial infarction in the 2 h following the onset of anger. The incidence was independent of the degree of risk factors, suggesting that anger was the independent trigger of the event [40].

Grief over the death of a close person was yet another trigger of myocardial infarction. The risk of acute cardiac events was elevated 21-fold in the first 24 h after the onset of grief [41]. The deleterious effect of grief was more pronounced in patients with high cardiovascular risk factors.

The exact mechanisms of anger, grief, and various events leading to severe emotional stress in causing acute myocardial infarction are not clear. It is likely related to intense sympathetic nerve stimulation with the increase in heart rate and elevated blood pressure, leading to elevated double product. Poor compliance with medication, such as missing beta-blocker medication doses, may contribute to the increased risk. One important study suggests that anger and severe emotional stress lead to coronary vasoconstriction. Boltwood et al [42] studied 12 patients during coronary angiography in a setting of myocardial ischemia. During the angiogram, and when the patients recalled an event that caused anger, there was a decrease in the diameter of the coronary artery at the diseased coronary segment. The vasoconstriction was more pronounced when the anger scale was elevated. That vasoconstriction was present in the coronary segments with underlying atherosclerosis may explain the deleterious effect of anger in patients with known coronary disease or with increased coronary risk factors.

An important trigger for increased cardiac events is marital stress. The reason for emphasizing this type of trigger is because it occurs in a well-defined group of patients. Contrary to increased stress from earthquakes and other natural disasters that are unpredictable, marital stress can be easily identified, and a management plan can be considered. Orth-Gomer et al [43] studied a group of 292 consecutive females with a mean age of 56 years, who were hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction. Patients were prospectively followed for about 5 years. The degree of marital stress was assessed by trained behavioral scientists using the Stockholm Marital Stress Scale. In women with a high marital stress score, there was a 2.9-fold increase in cardiac events, including cardiac death, recurrent myocardial infarction, and revascularization. It seems that two mechanisms were responsible for this finding. The first mechanism was poor adherence to a healthy lifestyle and poor compliance with medications. The second factor was the negative effect of stress in neuro-endocrine regulatory functions, with many side effects, such as increased blood pressure. Attempting to pay attention to these negative mechanisms may help diminish the increase in cardiac events.

| Snow Shoveling | ▴Top |

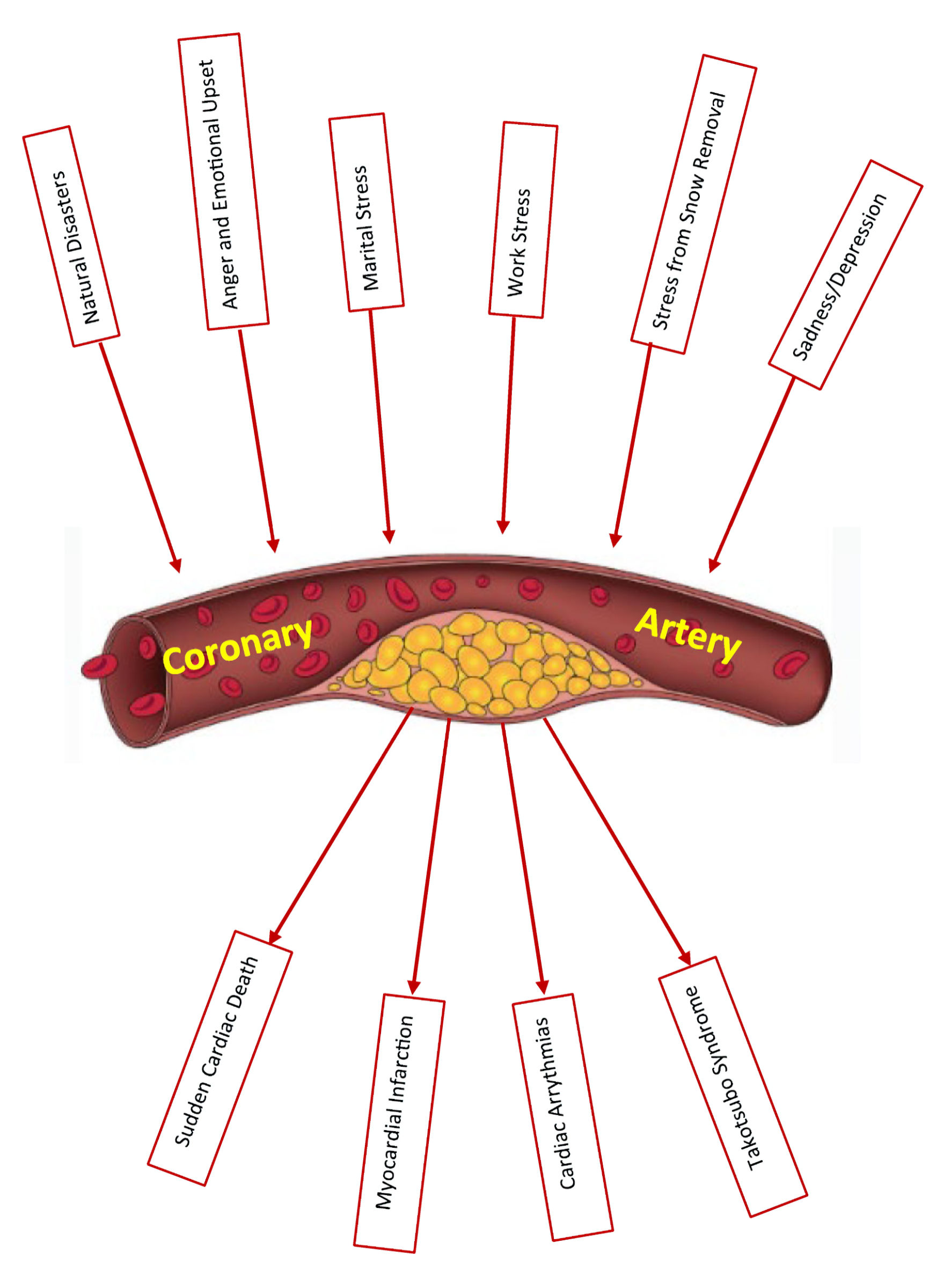

There is a clear increase in the incidence of acute myocardial infarction and cardiac death during severe snowstorms and blizzards. These events appear to be related to the physical activity of removing the snow but not necessarily related to the effect of decreased air temperature [28]. The majority of reports were from the Midwest, with an increase in cardiac events in the days following a storm [44-47]. The incidence is higher in men, and there is no clear difference in the clinical features or risk factors between myocardial infarctions during snowstorms and those occurring during control periods. The incidence appears to be related to the degree of physical activity rather than to the degree of cold weather. To investigate the effects of significant physical exertion during snow removal in healthy men, Franklin et al [48] measured heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen uptake in 10 healthy volunteers. Each individual subject cleared two 10-cm-high, 15-cm-long tracts of wet, heavy snow in cold weather. The effort of snow removal rivaled that of maximal treadmill testing. This may help explain why performing substantial amounts of snow removal during severe storms - particularly in people with known coronary disease - may increase the incidence of coronary events during blizzards. These events in published reports were more prevalent in men, particularly in those with known coronary artery disease. Snow shoveling is associated with increased oxygen demand and may also contribute to the rupture of coronary plaques. Hammoudeh et al [49] performed angiography in 15 patients who developed acute myocardial infarction during the blizzard and snowstorms in New Jersey in 1996. Nine patients had evidence of atherosclerotic plaque rupture, and six patients showed evidence of coronary thrombosis. This report was unique in describing the pathology of snow-induced coronary events in live patients. A summary of various triggers for acute coronary events is depicted in Figure 1.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Various triggers of acute coronary syndrome. |

| Seasonal Variations and Cardiac Events | ▴Top |

In most studies, acute myocardial infarction may increase during the winter months. Multiple factors may be responsible for this finding, including increased cardiac workload, higher blood pressure, and elevated fibrinogen during the winter season. Particularly alarming is the significant increase in mortality in patients who develop acute myocardial infarction during the winter months [50]. Kloner et al studied cardiac death between the years 1985 and 1996 in southern California, an area known for its mild winters. The highest cardiac mortality occurred during the months of December and January [51]. It is possible that in addition to the expected risk of winter temperatures, the increased mental stress during these months associated with the winter holiday season may play a role in the increased rate of coronary artery disease mortality.

| Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy | ▴Top |

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a syndrome described over three decades ago that may resemble acute coronary syndromes. This syndrome is triggered by severe physical or emotional stress that results in severe left ventricular dysfunction with characteristic apical ballooning. While the exact mechanism is still not clear, it seems that significant catecholamine surge leads to acute myocyte dysfunction, microvascular damage, and even transient coronary artery obstruction [52]. The syndrome is most common in women. Some of the emotional stressors that have been described to trigger Takotsubo cardiomyopathy include depression, fear of speech, robbery, fear of surgery, move to another city, change in job, debt, grief, arguments with family members, natural disasters, and car accidents [53]. Surprisingly, even certain positive events may trigger the syndrome, including winning a lottery jackpot, birthday party, wedding, birth of a grandchild and others. All of these emotional triggers are associated with an increase in sympathetic activity which may lead to a catecholamine surge. While most cases are reversible, during the acute phase, some cases may be fatal. Definitive diagnosis usually is achieved by two-dimensional echocardiography and coronary angiography.

| Conclusions | ▴Top |

Most primary care providers and many patients are well aware of coronary risk factors, and in general, they implement these preventative measures quite well [54]. This may explain the progress in cardiac care in developed countries. This report, however, focused on triggers of myocardial infarction and the entire scope of acute coronary syndrome. Natural disasters, such as earthquakes, are an important trigger of cardiac death and myocardial infarction. It is important that in planning for such disasters, adequate cardiac care should be arranged to manage the increased demand during these situations. There is evidence in the literature that stress reduction may have benefits in the cardiac patient. Blumenthal et al (1997) assessed the cumulative time to cardiovascular events in cardiac patients randomized to usual care, exercise, versus stress management [55]. Stress management was associated with significantly lower adverse cardiac event rates compared to usual care. Exercise was associated with a nonsignificant improvement over usual care. Yoga, meditation, and tai chi are beneficial in managing stress and anxiety; however, their role in decreasing cardiac events are not well studied [56, 57].

Little attention, however, has been given to several types of emotional stress in life, whether in marital relationships, in the work situation, or others [58]. By managing emotional stress or controlling anger, we can attempt to decrease the incidence of cardiac events. Stress reduction programs may include exercises, breathing exercises, meditation, massage, and other psychologic approaches. Avoiding certain forms of heavy exertion, such as snow shoveling, may be recommended. Enrolling in organized exercise programs to enhance preconditioning is beneficial. Some regular medication, such as aspirin and beta-blockers, may provide some protection against cardiac events. This is of paramount importance in patients with known coronary artery disease or significant risk factors for atherosclerosis. During specific natural disasters or at work or family stress, consider giving oral aspirin and a beta-blocker, which may mitigate acute cardiac events. An organized program for psychotherapy may be developed for cardiac patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation programs, particularly for those patients with severe stress or with uncontrollable bouts of anger.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Kloner’s work was supported in part by the Francis Bacon Foundation and the Pasadena Community Foundation-John and Lucille Crumb Medical Research Endowment to HMRI, and by the Marylou Ingram Endowment to HMRI. The authors acknowledge Marie Fleisner for editorial assistance with the paper and for creating the figure.

Financial Disclosure

None to report.

Conflict of Interest

None to report on the part of either author.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to the conception of the paper, literature search, and manuscript writing. In addition, Dr. Kloner provided critical revision and editing of the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Newby DE. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction: beyond the vulnerable plaque. Heart. 2010;96(15):1247-1251.

doi pubmed - Giannarelli C. Single-point vulnerabilities in atherosclerotic plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(23):2228-2230.

doi pubmed - Bentzon JF, Otsuka F, Virmani R, Falk E. Mechanisms of plaque formation and rupture. Circ Res. 2014;114(12):1852-1866.

doi pubmed - Johnstone MT, Mittleman M, Tofler G, Muller JE. The pathophysiology of the onset of morning cardiovascular events. Am J Hypertens. 1996;9(4 Pt 3):22S-28S.

doi pubmed - Hammadah M, Alkhoder A, Al Mheid I, Wilmot K, Isakadze N, Abdulhadi N, Chou D, et al. Hemodynamic, catecholamine, vasomotor and vascular responses: Determinants of myocardial ischemia during mental stress. Int J Cardiol. 2017;243:47-53.

doi pubmed - Lima BB, Hammadah M, Kim JH, Uphoff I, Shah A, Levantsevych O, Almuwaqqat Z, et al. Association of Transient Endothelial Dysfunction Induced by Mental Stress With Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Men and Women With Coronary Artery Disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(10):988-996.

doi pubmed - Moazzami K, Sullivan S, Wang M, Okoh AK, Almuwaqqat Z, Pearce B, Shah AJ, et al. Cardiovascular Reactivity to Mental Stress and Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2025;14(3):e034683.

doi pubmed - Yin H, Liu F, Bai B, Liu Q, Liu Y, Wang H, Wang Y, et al. Myocardial blood flow mechanism of mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia in women with ANOCA. iScience. 2024;27(12):111302.

doi pubmed - Daoulah A, Al-Faifi SM, Hersi AS, Dinas PC, Youssef AA, Alshehri M, Baslaib F, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in relation to physical and emotional stress: a retrospective study in 4 Arab Gulf countries. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2021;46(3):100484.

doi pubmed - Dai N, Tang X, Weng X, Cai H, Zhuang J, Yang G, Zhou F, et al. Stress-related neural activity associates with coronary plaque vulnerability and subsequent cardiovascular events. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023;16(11):1404-1415.

doi pubmed - Radfar A, Abohashem S, Osborne MT, Wang Y, Dar T, Hassan MZO, Ghoneem A, et al. Stress-associated neurobiological activity associates with the risk for and timing of subsequent Takotsubo syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(19):1898-1908.

doi pubmed - Roth L, Rombouts M, Schrijvers DM, Lemmens K, De Keulenaer GW, Martinet W, De Meyer GR. Chronic intermittent mental stress promotes atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability, myocardial infarction and sudden death in mice. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242(1):288-294.

doi pubmed - Schwartz BG, Kloner RA, Naghavi M. Acute and subacute triggers of cardiovascular events. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122(12):2157-2165.

doi pubmed - Gullette EC, Blumenthal JA, Babyak M, Jiang W, Waugh RA, Frid DJ, O'Connor CM, et al. Effects of mental stress on myocardial ischemia during daily life. JAMA. 1997;277(19):1521-1526.

pubmed - Strike PC, Magid K, Brydon L, Edwards S, McEwan JR, Steptoe A. Exaggerated platelet and hemodynamic reactivity to mental stress in men with coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(4):492-500.

doi pubmed - Yeung AC, Vekshtein VI, Krantz DS, Vita JA, Ryan TJ, Jr., Ganz P, Selwyn AP. The effect of atherosclerosis on the vasomotor response of coronary arteries to mental stress. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(22):1551-1556.

doi pubmed - Jiang W, Babyak M, Krantz DS, Waugh RA, Coleman RE, Hanson MM, Frid DJ, et al. Mental stress—induced myocardial ischemia and cardiac events. JAMA. 1996;275(21):1651-1656.

doi pubmed - Sonaglioni A, Rigamonti E, Nicolosi GL, Lombardo M. Prognostic value of modified haller index in patients with suspected coronary artery disease referred for exercise stress echocardiography. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2021;31(2):85-95.

doi pubmed - Schwartz BG, French WJ, Mayeda GS, Burstein S, Economides C, Bhandari AK, Cannom DS, et al. Emotional stressors trigger cardiovascular events. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(7):631-639.

doi pubmed - Kloner RA. Lessons learned about stress and the heart after major earthquakes. Am Heart J. 2019;215:20-26.

doi pubmed - Katsouyanni K, Kogevinas M, Trichopoulos D. Earthquake-related stress and cardiac mortality. Int J Epidemiol. 1986;15(3):326-330.

doi pubmed - Armenian HK, Melkonian AK, Hovanesian AP. Long term mortality and morbidity related to degree of damage following the 1998 earthquake in Armenia. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(11):1077-1084.

doi pubmed - Niiyama M, Tanaka F, Nakajima S, Itoh T, Matsumoto T, Kawakami M, Naganuma Y, et al. Population-based incidence of sudden cardiac and unexpected death before and after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Iwate, northeast Japan. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(3):e000798.

doi pubmed - Kloner RA, Leor J, Poole WK, Perritt R. Population-based analysis of the effect of the Northridge Earthquake on cardiac death in Los Angeles County, California. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30(5):1174-1180.

doi pubmed - Leor J, Kloner RA. The Northridge earthquake as a trigger for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(14):1230-1232.

doi pubmed - Muller JE, Abela GS, Nesto RW, Tofler GH. Triggers, acute risk factors and vulnerable plaques: the lexicon of a new frontier. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23(3):809-813.

doi pubmed - Semenza JC, Rubin CH, Falter KH, Selanikio JD, Flanders WD, Howe HL, Wilhelm JL. Heat-related deaths during the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(2):84-90.

doi pubmed - Glass RI, Zack MM, Jr. Increase in deaths from ischaemic heart-disease after blizzards. Lancet. 1979;1(8114):485-487.

doi pubmed - Kloner RA. Natural and unnatural triggers of myocardial infarction. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;48(4):285-300.

doi pubmed - Ghosh AK, Demetres MR, Geisler BP, Ssebyala SN, Yang T, Shapiro MF, Setoguchi S, et al. Impact of hurricanes and associated extreme weather events on cardiovascular health: a scoping review. Environ Health Perspect. 2022;130(11):116003.

doi pubmed - Swerdel JN, Janevic TM, Cosgrove NM, Kostis JB, Myocardial Infarction Data Acquisition System Study G. The effect of Hurricane Sandy on cardiovascular events in New Jersey. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(6):e001354.

doi pubmed - Peters MN, Moscona JC, Katz MJ, Deandrade KB, Quevedo HC, Tiwari S, Burchett AR, et al. Natural disasters and myocardial infarction: the six years after Hurricane Katrina. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(4):472-477.

doi pubmed - Wilbert-Lampen U, Leistner D, Greven S, Pohl T, Sper S, Volker C, Guthlin D, et al. Cardiovascular events during World Cup soccer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(5):475-483.

doi pubmed - Kloner RA, McDonald S, Leeka J, Poole WK. Comparison of total and cardiovascular death rates in the same city during a losing versus winning super bowl championship. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103(12):1647-1650.

doi pubmed - Schwartz BG, McDonald SA, Kloner RA. Super Bowl outcome's association with cardiovascular death. Clin Res Cardiol. 2013;102(11):807-811.

doi pubmed - Leeka J, Schwartz BG, Kloner RA. Sporting events affect spectators' cardiovascular mortality: it is not just a game. Am J Med. 2010;123(11):972-977.

doi pubmed - Tofler GH, Stone PH, Maclure M, Edelman E, Davis VG, Robertson T, Antman EM, et al. Analysis of possible triggers of acute myocardial infarction (the MILIS study). Am J Cardiol. 1990;66(1):22-27.

doi pubmed - Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Mulry RP, Tofler GH, Jacobs SC, Friedman R, et al. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction onset by episodes of anger. Determinants of Myocardial Infarction Onset Study Investigators. Circulation. 1995;92(7):1720-1725.

doi pubmed - Mostofsky E, Maclure M, Tofler GH, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. Relation of outbursts of anger and risk of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112(3):343-348.

doi pubmed - Mostofsky E, Penner EA, Mittleman MA. Outbursts of anger as a trigger of acute cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(21):1404-1410.

doi pubmed - Mostofsky E, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Tofler GH, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. Risk of acute myocardial infarction after the death of a significant person in one's life: the Determinants of Myocardial Infarction Onset Study. Circulation. 2012;125(3):491-496.

doi pubmed - Boltwood MD, Taylor CB, Burke MB, Grogin H, Giacomini J. Anger report predicts coronary artery vasomotor response to mental stress in atherosclerotic segments. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72(18):1361-1365.

doi pubmed - Orth-Gomer K, Wamala SP, Horsten M, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Schneiderman N, Mittleman MA. Marital stress worsens prognosis in women with coronary heart disease: The Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Study. JAMA. 2000;284(23):3008-3014.

doi pubmed - Glass RI, Wiesenthal AM, Zack MM, Preston M. Risk factors for myocardial infarction associated with the Chicago snowstorm of jan 13- 15, 1979. JAMA. 1981;245(2):164-165.

pubmed - Baker-Blocker A. Winter weather and cardiovascular mortality in Minneapolis-St. Paul. Am J Public Health. 1982;72(3):261-265.

doi pubmed - Franklin BA, Bonzheim K, Gordon S, Timmis GC. Snow shoveling: a trigger for acute myocardial infarction and sudden coronary death. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(10):855-858.

doi pubmed - Chowdhury PS, Franklin BA, Boura JA, Dragovic LJ, Kanluen S, Spitz W, Hodak J, et al. Sudden cardiac death after manual or automated snow removal. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92(7):833-835.

doi pubmed - Franklin BA, Hogan P, Bonzheim K, Bakalyar D, Terrien E, Gordon S, Timmis GC. Cardiac demands of heavy snow shoveling. JAMA. 1995;273(11):880-882.

pubmed - Hammoudeh AJ, Haft JI. Coronary-plaque rupture in acute coronary syndromes triggered by snow shoveling. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(26):2001.

doi pubmed - Miao H, Bao W, Lou P, Chen P, Zhang P, Chang G, Hu X, et al. Relationship between temperature and acute myocardial infarction: a time series study in Xuzhou, China, from 2018 to 2020. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2645.

doi pubmed - Kloner RA, Poole WK, Perritt RL. When throughout the year is coronary death most likely to occur? A 12-year population-based analysis of more than 220 000 cases. Circulation. 1999;100(15):1630-1634.

doi pubmed - Milinis K, Fisher M. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: pathophysiology and treatment. Postgrad Med J. 2012;88(1043):530-538.

doi pubmed - Ghadri JR, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, Sharkey S, Dote K, Akashi YJ, Cammann VL, et al. International expert consensus document on takotsubo syndrome (Part I): clinical characteristics, diagnostic criteria, and pathophysiology. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(22):2032-2046.

doi pubmed - Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937-952.

doi pubmed - Blumenthal JA, Jiang W, Babyak MA, Krantz DS, Frid DJ, Coleman RE, Waugh R, et al. Stress management and exercise training in cardiac patients with myocardial ischemia. Effects on prognosis and evaluation of mechanisms. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(19):2213-2223.

pubmed - Saeed SA, Cunningham K, Bloch RM. Depression and anxiety disorders: benefits of exercise, yoga, and meditation. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(10):620-627.

pubmed - Yang G, Li W, Klupp N, Cao H, Liu J, Bensoussan A, Kiat H, et al. Does tai chi improve psychological well-being and quality of life in patients with cardiovascular disease and/or cardiovascular risk factors? A systematic review. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022;22(1):3.

doi pubmed - Ferrie JE, Kivimaki M, Shipley MJ, Davey Smith G, Virtanen M. Job insecurity and incident coronary heart disease: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Atherosclerosis. 2013;227(1):178-181.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cardiology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.