| Cardiology Research, ISSN 1923-2829 print, 1923-2837 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cardiol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 16, Number 6, December 2025, pages 507-517

De Novo Acute Heart Failure Versus Acute Decompensated Chronic Heart Failure: Are There Differences in In-Hospital Outcomes and Mortality?

Juan David Pelaez-Martineza , Daniel Castilloa

, Jackelin Maingueza

, Sebastian Seni-Molinab

, Yorlany Rodasb

, Hoover O. Leon-Giraldoa, b

, Diana Cristina Carrilloa, b, c

, Juan David Lopez-Ponce de Leona, b, c

, Noel Alberto Floreza, c

, Pastor Olayaa, c

, Edilma Lucy Riverac

, Nancy Olayac

, Juan Esteban Gomez-Mesaa, b, c, d

aFacultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Icesi, Cali 760008, Colombia

bCentro de Investigaciones Clinicas (CIC), Fundacion Valle del Lili, Cali 760031, Colombia

cServicio de Cardiologia, Fundacion Valle del Lili, Cali 760031, Colombia

dCorresponding Author: Juan Esteban Gomez-Mesa, Servicio de Cardiologia, Fundacion Valle del Lili, Cali 760031, Colombia

Manuscript submitted August 19, 2025, accepted October 25, 2025, published online December 20, 2025

Short title: De Novo vs. Chronic Decompensated HF Outcomes

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cr2135

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Heart failure (HF) is a major cause of global morbidity and mortality. Patients with acute decompensated chronic HF (ad-CHF) usually have more comorbidities, whereas those with de novo acute HF (dn-AHF) may have a more severe clinical presentation. Despite extensive research on HF, comparative data on in-hospital outcomes and mortality between these groups are scarce in Latin American countries. The aim of this study was to evaluate differences in in-hospital complications and mortality among patients hospitalized with either dn-AHF or ad-CHF.

Methods: An ambispective study was conducted at a tertiary hospital in Colombia, including 780 patients hospitalized for acute HF. Patients were classified as dn-AHF or ad-CHF, and sociodemographic, clinical, and in-hospital outcomes were compared using bivariate analysis. A Firth penalized logistic regression model was used to assess the association between dn-AHF and in-hospital mortality.

Results: Of these patients, 39.2% had dn-AHF, and 60.8% had ad-CHF. Median ages were 67 (interquartile range (IQR): 56 - 76) and 66 (IQR: 55 - 79) years, respectively. Both groups had a predominance of reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, with median values of 30% in ad-CHF and 34% in dn-AHF. Ad-CHF patients had more comorbidities, whereas dn-AHF patients showed higher rates of cardiac and non-cardiac complications. Intensive care unit (ICU) admission rates were similar, the need for invasive mechanical ventilation (P < 0.001) and the occurrence of infections (P = 0.049) were significantly more frequent in patients with dn-AHF. In-hospital mortality was higher in dn-AHF than ad-CHF (9.8% vs. 5.5%, P = 0.023). After adjustment, dn-AHF remained independently associated with greater in-hospital mortality (odds ratio (OR): 1.87; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.07 - 3.31; P = 0.029).

Conclusions: Patients with dn-AHF experienced more in-hospital complications and higher mortality than those with ad-CHF, despite similar ICU admission rates and fewer comorbidities. These results highlight the prognostic importance of dn-AHF and underscore the need for early identification, vigilant monitoring, and phenotype-specific management from admission to improve outcomes, particularly among patients with reduced ejection fraction.

Keywords: Acute decompensated chronic heart failure; De novo acute heart failure; In-hospital mortality; Complications

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Heart failure (HF) is a significant global health problem, affecting more than 64 million individuals worldwide [1]. Despite advancements in pharmacotherapy, its mortality rate remains high, reaching 6.7-17.9% at discharge and 10.9% at 30 days in the Latin American context [2-4]. Data from the Rochester Epidemiology Project, a population-based registry in Minnesota, USA, revealed that patients with a history of HF are rehospitalized an average of 0.87 times per year, making HF one of the most frequent causes of hospitalization [5, 6].

Clinical manifestation of acute HF (AHF) can occur either as acute decompensated chronic HF (ad-CHF) or as a de novo AHF (dn-AHF) [7, 8]. Approximately one-third of AHF cases correspond to the latter modality [9]. It is notable that 3-month post-discharge mortality is significantly higher in patients with ad-CHF compared to dn-AHF [9, 10], although this trend does not seem to hold for in-hospital mortality [10, 11].

Differentiation of in-hospital mortality between dn-AHF and ad-CHF events is imperative. Decompensatory episodes often affect older patients with significant comorbidities, including a history of previous HF hospitalizations. Scientific evidence on this matter remains inconclusive. While some studies report higher in-hospital mortality in dn-AHF episodes [10-12], others show the opposite or find no statistically significant differences [11].

Despite recent improvements in the epidemiological and clinical characterization of HF in Latin America, the comparison of in-hospital mortality between patients with dn-AHF and ad-CHF has not been widely reported, resulting in a significant knowledge gap in our continent [13, 14]. Consequently, our study aims to evaluate in-hospital outcomes and mortality in patients with a dn-AHF event versus those with an ad-CHF event in a high-complexity hospital in Colombia, South America.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This study was conducted with data from the Registro Institucional de Falla Cardiaca Aguda (RIFACA) of Fundacion Valle del Lili (FVL) in Cali, Colombia. This is an ongoing ambispective observational registry, which combines retrospective and prospective data collection, of patients diagnosed with AHF, who are managed by the Heart Failure Unit of the Cardiology Service at FVL in Cali, Colombia.

Data collection

The recruitment period started on January 1, 2011, and is ongoing to the current date. The study population comprised 780 patients over 18 years old who were diagnosed with AHF at admission or during hospitalization, with data available on the chronicity of their diagnosis as of December 2021. All data were collected from medical records, including sociodemographic variables, medical history (cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular conditions), pharmacological therapy before and during hospitalization, clinical manifestations at admission and discharge, HF classification, laboratory and imaging results, cardiovascular interventions, complications (both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular), functional status at discharge, prescribed medication at discharge, and discharge condition (alive or deceased).

Statistical analysis

A bivariate analysis was conducted to characterize the study population and to assess differences in hospital outcomes and mortality between dn-AHF and ad-CHF patients. The normality of quantitative variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For variables meeting the normality assumption, the mean was used as the measure of central tendency and the standard deviation (SD) as the measure of dispersion; otherwise, the median and interquartile range (IQR) were reported. Categorical variables were summarized as absolute frequencies and percentages.

Comparisons between groups based on the study population were conducted according to the type of variable. Quantitative variables were analyzed using the Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney test, depending on whether the normality assumption was met. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Additionally, we used Firth penalized logistic regression to model the association between dn-AHF and in-hospital mortality, accounting for potential small-sample bias. We initially specified a fully adjusted model including baseline covariates selected based on clinical relevance: age, sex, coronary artery disease (CAD), diabetes mellitus (DM), thyroid disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and valvular heart disease. A backward elimination approach was then applied, sequentially removing variables that were not statistically significant, did not act as confounders, and did not improve model fit according to the likelihood ratio test. Model 4, which included sex, CAD, and COPD as covariates, was retained as the final model for its balance between clinical interpretability and parsimony.

All analyses were conducted using available data for each variable. Proportions and summary statistics were calculated based solely on patients with available data for the specific variable, without applying any imputation methods. Missing data were < 5% for most variables; those exceeding this threshold, or when relevant, were explicitly reported to ensure transparency.

Ethical considerations

This registry adheres to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki [15]. The study protocol was approved by the Comite de Etica en Investigacion Biomedica (CEIB) of FVL (approval No. 869). In accordance with Resolution 8430 of 1993 issued by the Colombian Ministry of Health, the protocol is classified as minimal risk, as it does not involve additional interventions exceeding standard clinical practice. Accordingly, the CEIB waived the requirement to obtain informed consent from participating patients. Participant identities were protected through record coding and restricted access.

| Results | ▴Top |

General characteristics

The study included 780 patients with AHF, classified into two groups based on the chronicity of their HF diagnosis: 306 (39.2%) patients with dn-AHF and 474 (60.8%) patients with ad-CHF. The age distribution showed a median age of 66 years (IQR: 56.0 - 76.0) in the ad-CHF group and 67 years (IQR: 55.0 - 79.0) in the dn-AHF group. The proportion of male patients was similar in both groups, with 58.8% in the ad-CHF group and 53.7% in the dn-AHF group. The median left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was significantly lower in the ad-CHF group (30.0%, IQR: 20.0 - 45.0) compared to the dn-AHF group (34.0%, IQR: 25.0 - 45.0; P = 0.001) (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population |

The most frequent etiology of HF in both groups was ischemic; however, it was significantly higher in the dn-AHF group (30.0% in ad-CHF vs. 37.6% in dn-AHF; P = 0.002). In the dn-AHF group, idiopathic etiology was the second most common (15.7% vs. 10.5%), whereas in the ad-CHF group, dilated cardiomyopathy was the second most common (21.7% vs. 10.1%) (Table 1).

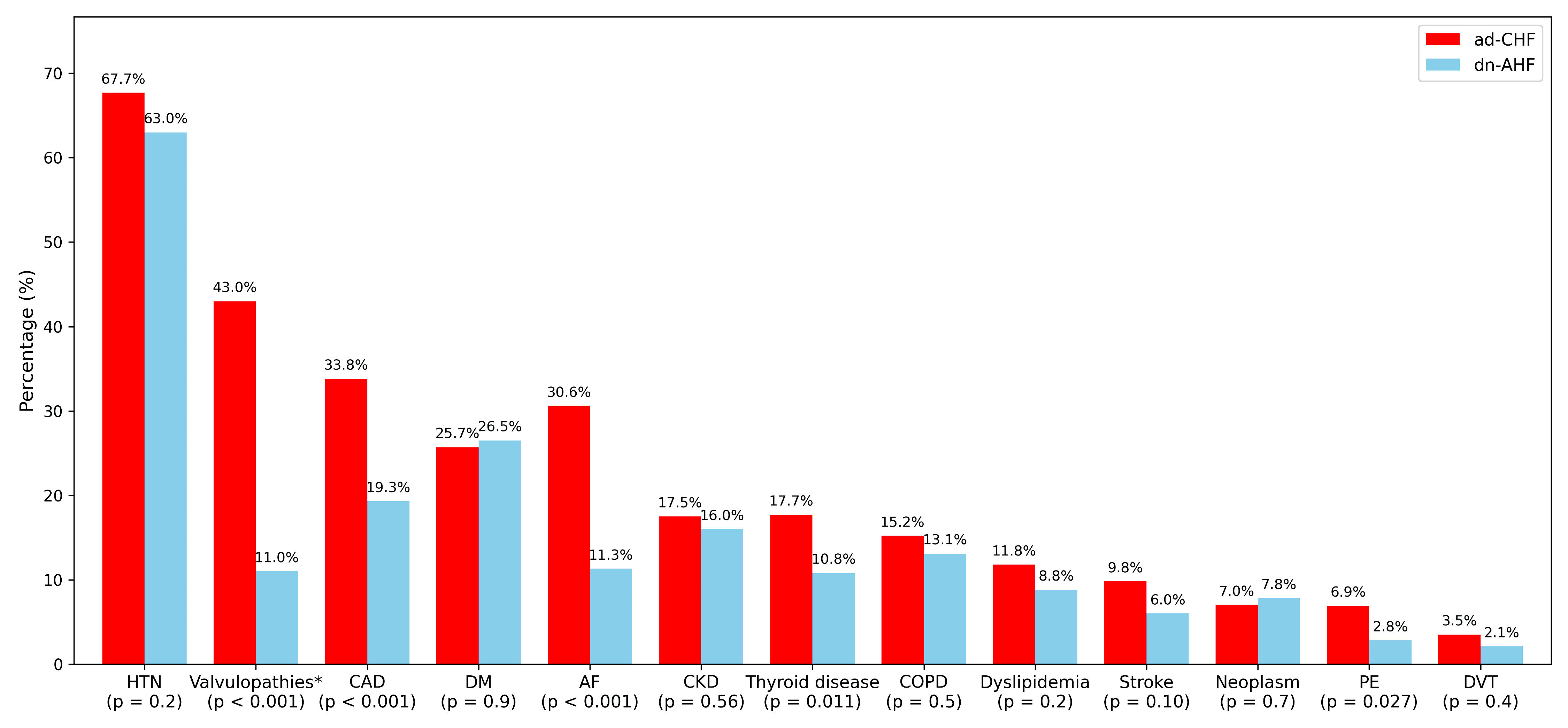

Regarding comorbidities, a higher prevalence of both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular conditions was observed in the ad-CHF group. Hypertension (HTN) remained the most common comorbidity in both groups, with no significant difference between them (67.7% in ad-CHF vs. 63.0% in dn-AHF; P = 0.2). Other comorbidities with significantly higher prevalence in the ad-CHF group included CAD (33.8% vs. 19.3%; P < 0.001), atrial fibrillation (AF) (30.6% vs. 11.3%; P < 0.001), valvulopathies (43.0% vs. 11.0%; P < 0.001), pulmonary embolism (6.9% vs. 2.8%; P = 0.027), and thyroid disease (17.7% vs. 10.8%; P = 0.011) (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Comparison of comorbidities in patients with ad-CHF and dn-AHF. *Valvulopathies were analyzed as a composite variable including aortic (15.0% in ad-CHF vs. 4.6% in dn-AHF; P < 0.001), mitral (30.6% vs. 7.2%; P < 0.001), and tricuspid (15.2% vs. 3.3%; P < 0.001) disease. Missing data for CKD were present in 49 patients (10.3%) in the ad-CHF group and 32 patients (10.5%) in the dn-AHF group, accounting for 10.4% of the overall population. AF: atrial fibrillation; ad-CHF: acute decompensated chronic heart failure; dn-AHF: de novo acute heart failure; CAD: coronary artery disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; DM: diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension; PE: pulmonary embolism. |

Deep vein thrombosis (3.5% vs. 2.1%; P = 0.4), stroke (9.8% vs. 6.0%; P = 0.10), CKD (17.5% vs. 16.0%; P = 0.56), COPD (15.2% vs. 13.1%; P = 0.5), dyslipidemia (11.8% vs. 8.8%; P = 0.2), DM (25.7% vs. 26.5%; P = 0.9), and neoplasm (7.0% vs. 7.8%; P = 0.7) did not show statistically significant differences between groups. Notably, DM and neoplasm were the only comorbidities with a slightly higher numerical prevalence in the dn-AHF group.

Clinical presentation at admission

Clinical profiles at admission also differed significantly between groups (P < 0.001). Acute decompensation of chronic HF predominated in ad-CHF (75.7%), whereas acute coronary syndrome (ACS) with HF (23.2% vs. 9.1%), pulmonary edema (16.0% vs. 5.1%), and hypertensive AHF (6.9% vs. 2.3%) were more frequent in dn-AHF. Cardiogenic shock occurred in both groups, slightly more often in dn-AHF (7.2% vs. 5.1%).

Chest pain was the predominant symptom among patients with dn-AHF (40.2% vs. 25.7%, P < 0.001), whereas orthopnea was more frequently reported in the ad-CHF group (41.4% vs. 30.7%, P = 0.003). Other symptoms, such as paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea and jugular venous distention, were also more prevalent in the ad-CHF group. Vital signs on admission showed that patients with dn-AHF had a higher median heart rate, higher median blood pressure, and a lower proportion of oxygen saturation above 92% compared to the ad-CHF group (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 2. Clinical, Hemodynamic and Biomarker Profile at Admission |

Patients with ad-CHF exhibited a higher prevalence of more advanced New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classes (III and IV), while patients with dn-AHF were more frequently classified in lower NYHA classes (I and II) (P < 0.001). The distribution of Stevenson hemodynamic profiles also differed significantly between the groups (P < 0.001). Profiles A and B were more prevalent among dn-AHF patients, whereas profiles C and L were more frequent in the ad-CHF group. Stevenson profile B was the most prevalent in both groups (Table 2).

Regarding laboratory parameters, patients with ad-CHF exhibited slightly lower hemoglobin concentrations and higher N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and creatinine levels. In contrast, patients with dn-AHF exhibited significantly higher leukocyte counts and troponin I levels, both reaching statistical significance (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

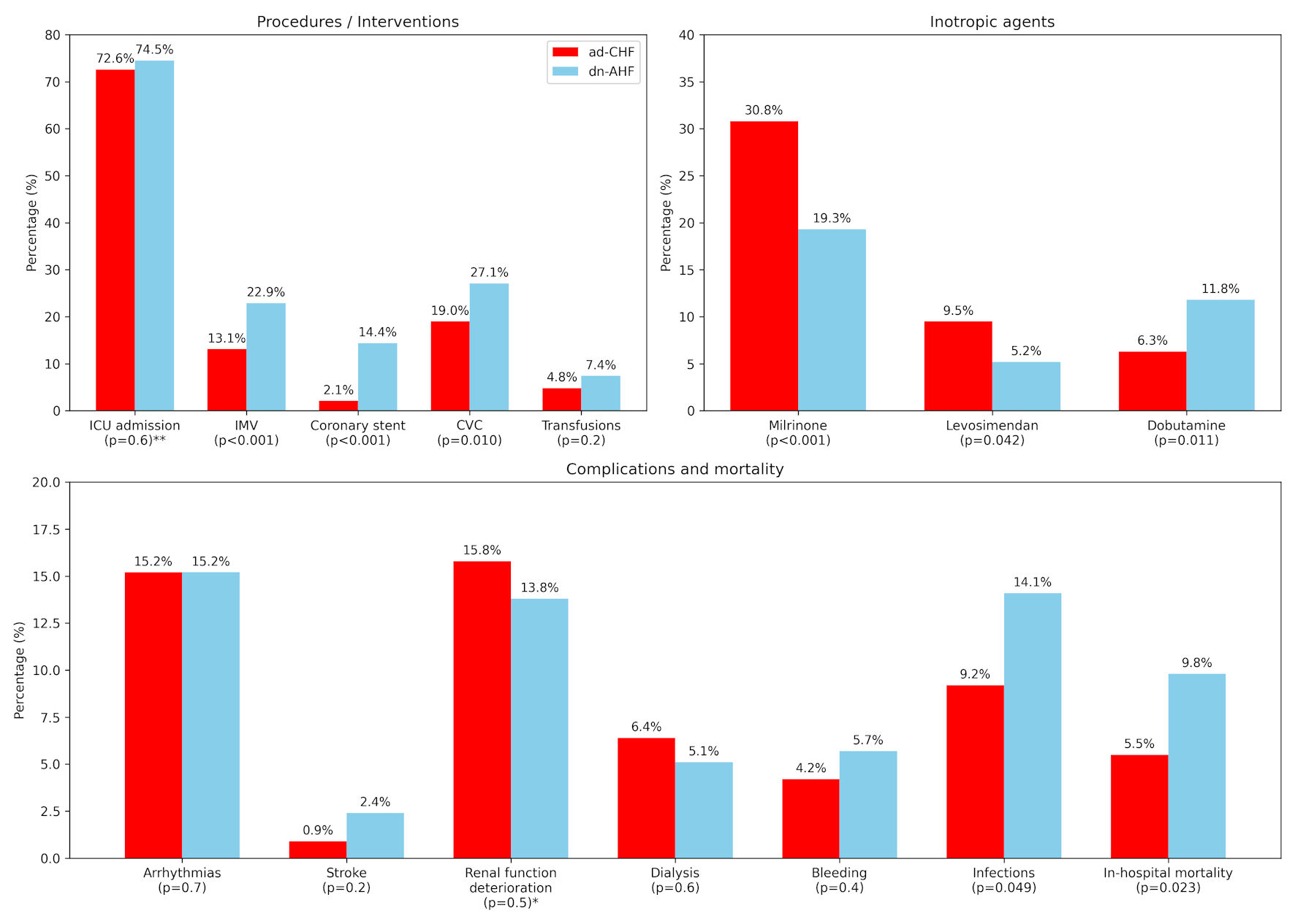

During hospitalization, a higher requirement for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) was observed in the dn-AHF group (22.9%) compared to the ad-CHF group (13.1%) (P < 0.001). Additionally, the dn-AHF group had a significantly higher requirement for coronary stenting (14.4% vs. 2.1%, P < 0.001) and central venous catheter placement (27.1% vs. 19.0%, P = 0.010). In contrast, intensive care unit (ICU) admission rates (P = 0.6), median ICU stay (P = 0.7) and transfusion requirements (P = 0.2) did not differ significantly between groups. Regarding intravenous inotropic agents, the ad-CHF group had a greater requirement for milrinone (30.8% vs. 19.3%, P < 0.001) and levosimendan (9.5% vs. 5.2%, P = 0.042), while the dn-AHF group showed a higher use of dobutamine (11.8% vs. 6.3%, P = 0.011) (Fig. 2).

Click for large image | Figure 2. In-hospital interventions, inotropic agents, and clinical outcomes in patients with ad-CHF and dn-AHF. *Renal function deterioration: increase of more than 0.5 mg/dL in baseline or reported creatinine at admission. **Among those admitted to the ICU, median stay was 5.0 days (IQR 3.0 - 9.0) in the ad-CHF group and 5.0 days (IQR 3.0 - 10.0) in the dn-AHF group; ICU-stay data were missing for 203 (42.9%) ad-CHF and 119 (38.9%) dn-AHF patients. CVC: central venous catheter; ad-CHF: acute decompensated chronic heart failure; dn-AHF: de novo acute heart failure; HF: heart failure; ICU: intensive care unit; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; IQR: interquartile range. |

Arrhythmias were the most frequent cardiovascular complication in both groups (15.2% vs. 15.2%; P = 0.7). Among non-cardiovascular complications, infections were significantly more prevalent in the dn-AHF group (14.1% vs. 9.2%, P = 0.049) (Table 3). A significant difference was observed in in-hospital mortality; patients with dn-AHF had a mortality rate of 9.8%, compared to 5.5% in the ad-CHF group (P = 0.023) (Fig. 2).

Click to view | Table 3. In-Hospital Mortality Causes in Ad-CHF and Dn-AHF Groups |

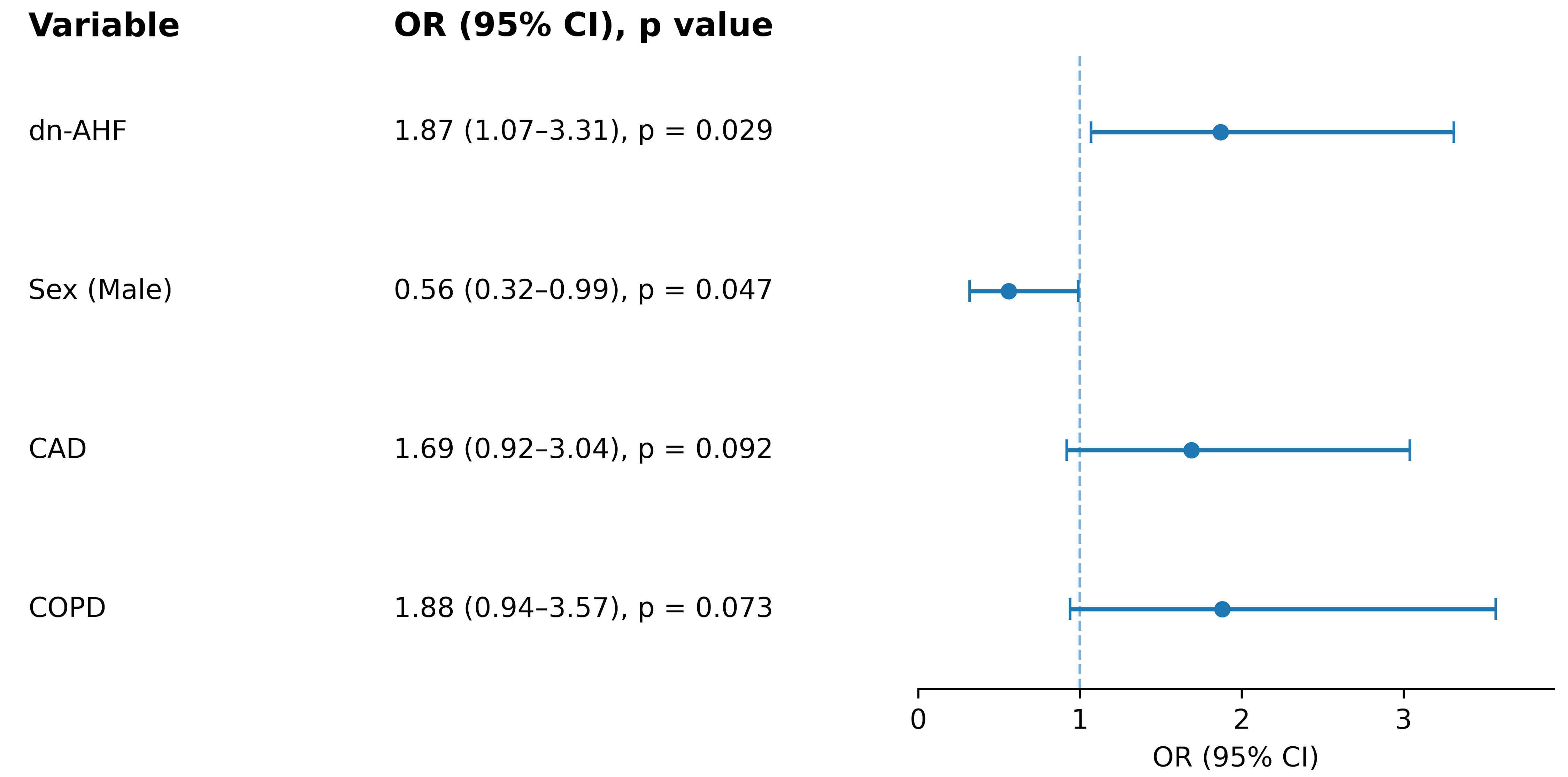

In the multivariable model, dn-AHF was independently associated with in-hospital mortality (odds ratio (OR): 1.87; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.07 - 3.31; P = 0.029). In contrast, male sex was associated with a lower risk of in-hospital death (OR: 0.56; 95% CI: 0.32 - 0.99; P = 0.047). Although both CAD and COPD showed positive trends toward increased mortality risk (CAD (OR: 1.69; 95% CI: 0.92 - 3.04; P = 0.092); COPD (OR: 1.88; 95% CI: 0.94 - 3.57; P = 0.073)); these associations did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Forest plot of Firth penalized multivariable logistic regression for in-hospital mortality. CAD: coronary artery disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; dn-AHF: de novo acute heart failure; OR: odds ratio. |

HF was the leading cause of death in both groups. Non-cardiovascular causes were more frequent in the dn-AHF group, with infections accounting for a notable proportion (16.0% in dn-AHF vs. 4.0% in ad-CHF) (Table 3).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Our study provides a clear perspective on the differences in complications and mortality between patients with dn-AHF and ad-CHF. Significant disparities were observed, as individuals with dn-AHF experienced nearly twice the in-hospital mortality of their ad-CHF counterparts. This excess mortality persisted despite similar ICU admission rates between the groups and a greater comorbidity burden in patients with ad-CHF. These findings are particularly relevant in Colombia and Latin America, where healthcare settings and patient profiles may differ from those reported in international studies, and where region-specific evidence on acute HF remains scarce.

Demographics and clinical characteristics

Our distribution between ad-CHF and dn-AHF presentations is similar to that reported by Younis et al, who described a comparable proportion of dn-AHF among patients hospitalized with AHF [16]. Regarding demographics, the male predominance observed in our cohort has also been reported in previous studies, including that of Mulla et al [17]. The observed median age in both groups likely reflects the epidemiological profile of HF in the Americas, where patients tend to develop HF at earlier ages [18]. This trend may be further influenced by the male predominance in our cohort, as men are more likely to develop ACS leading to HF before the age of 70, whereas HF becomes more prevalent among women after the age of 70 - 80 [19, 20].

Similarly, the clinical characteristics observed in our study align with previous reports, as the ad-CHF group exhibited a higher prevalence of congestive symptoms, including orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and jugular venous distension [21]. Additionally, the combined prevalence of Stevenson profiles B+C, indicative of congestive or combined hypoperfusive-congestive states, was higher in the ad-CHF group (83.4% vs. 79.1%). Consistently, patients with ad-CHF in our cohort also exhibited a greater burden of comorbidities compared with those presenting with dn-AHF. These observations are well supported by the literature, as a meta-analysis of 38,320 patients from 15 studies demonstrated that comorbidities such as HTN, ischemic heart disease, AF, and stroke were more prevalent in ad-CHF compared to dn-AHF patients [10].

The NYHA functional class profile at admission in ad-CHF patients predominantly presented with worse classes, aligned with data from a prospective study in Israel [16]. Although expected, this observation reinforces the link between chronic disease burden and worse functional status in ad-CHF and underscores the need for tailored management strategies informed by patients’ clinical history and comorbidity profile.

On the other hand, and in contrast to that study, our population showed statistically significant but clinically modest differences in hemoglobin and creatinine levels, which could be attributed to a lower prevalence of comorbidities compared to the Israeli population [16]. This may reflect broader epidemiological patterns, as HF in Latin America tends to present at younger ages and with distinct etiological profiles, including region-specific causes such as Chagas disease and hypertensive heart disease, which contribute to a lower overall burden of multimorbidity, known to increase with age in HF patients [22-24].

The elevated troponin I levels observed in our cohort, particularly among dn-AHF patients, are consistent with previous findings that associate this biomarker with adverse outcomes in AHF [25]. Similar to our findings, where a lower LVEF was observed in the ad-CHF group, the Spanish Acute Heart Failure Registry also reported a higher prevalence of patients with ad-CHF having an LVEF < 40%. A similar pattern was noted for patients with an LVEF between 40% and 49% [9]. These findings could be explained by the chronic progression and ventricular remodeling associated with the more heterogeneous etiological profile observed in ad-CHF. Likewise, in relation to the LVEF, the ad-CHF group exhibited a higher prevalence of cold profiles (C and L), which is consistent with existing literature linking these hypoperfusive profiles to more advanced left ventricular dysfunction [26].

Etiology and triggering factors for decompensation

Ischemic heart disease emerged as the most frequent etiology of HF in both groups, aligning with literature that identifies ischemic heart disease as the main cause of AHF [27]. According to a 2021 review, ACS was the most common triggering factor of both ad-CHF and dn-AHF events [10]. However, its greater prevalence among dn-AHF patients observed in our study provides important insights into its role within this specific HF subgroup. For instance, it has been shown in a meta-analysis that ACS is more commonly associated with dn-AHF presentations [10].

Interestingly, despite a higher prevalence of ischemia-related features, patients with dn-AHF had a lower documented history of CAD compared with those with ad-CHF. This finding aligns with previous studies showing that de novo episodes often develop in individuals without a prior diagnosis of ischemic heart disease, where an acute ischemic event acts as the initial trigger for HF onset [28]. While this pattern may reflect the natural course of first-time ischemic injury, it may also indicate underrecognition of subclinical CAD, potentially related to gaps in primary prevention, limited cardiovascular screening, poor adherence to medical follow-up and socioeconomic barriers to timely care. Addressing these systemic shortcomings is essential to prevent the progression from unrecognized ischemia to overt HF and to promote more equitable access to cardiovascular prevention and management in Colombia.

Additionally, it is well established that infections are a key trigger of acute HF events [7]. These observations closely relate to our findings, in which more than 10% of patients in both groups presented with infections as triggers, particularly in the dn-AHF group, where both a higher percentage and a higher median leukocyte count were observed.

Differences in in-hospital complications and mortality

Consistent with the similar rates of in-hospital renal function deterioration observed between groups, no significant difference was found in the need for dialysis. This is an interesting finding, as ad-CHF patients typically require more renal replacement therapy, a pattern often attributed to their greater comorbidity burden [29]. Likewise, neither the proportion of patients requiring ICU admission nor the length of stay in the ICU differed significantly between the ad-CHF and dn-AHF groups. Despite this, patients with ad-CHF less frequently required IMV in comparison with patients with dn-AHF (13.1% vs. 22.9%, P < 0.001), in line with recent studies [29], but in contrast to earlier investigations, such as the NOVICA study, which reported a higher use of IMV in patients with ad-CHF [11]. Similarly, the use of inotropic agents varied between the groups, with milrinone and levosimendan being more used in ad-CHF and dobutamine in dn-AHF, possibly reflecting a preference for sustained vasodilatory inotropic support in chronic decompensation versus rapid β1-mediated augmentation of cardiac output in acute settings [30]. Importantly, our findings regarding ICU length of stay should be interpreted with caution, given the considerable amount of missing data and the resulting potential for undetected differences between the groups.

The observation of a high frequency of both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular complications during hospitalization in dn-AHF patients and the greater need for IMV, further reinforce the notion of a more severe clinical course in this patient group. This could, in fact, relate to recent studies where de novo HF presentations, particularly in the setting of HF-related cardiogenic shock, have been associated with greater illness severity, higher rates of organ failure, and higher in-hospital mortality [31]. We speculate that, in our cohort, this pattern may be partly driven by a greater ischemic burden in dn-AHF. In fact, several findings from our study support this interpretation, including the higher prevalence of ischemic heart disease in dn-AHF, the significantly greater need for coronary stenting, elevated troponin I levels, more frequent chest pain on admission, and more frequent presentations of ACS complicated by HF. Alternatively, the absence of prior adaptation to chronic HF or optimized medical therapy in dn-AHF patients may increase their vulnerability to multiorgan dysfunction and poor outcomes.

Despite a similar ICU requirement, dn-AHF patients in our study exhibited a higher rate of in-hospital mortality compared to those with ad-CHF. This difference remained statistically significant after adjustment for covariates. This finding aligns with reports from various regions of the world that have described slightly higher in-hospital mortality among dn-AHF patients, although other studies have found the opposite or no significant difference between the two groups [10]. In contrast, a study conducted in the UK reported a higher in-hospital mortality rate among ad-CHF patients, although this difference did not reach statistical significance [32]. Overall, these findings highlight the variability in the association between the chronicity of HF and in-hospital mortality, likely reflecting differences in patient profiles, healthcare systems, and study definitions. Our study adds to this ongoing discussion and underscores the need for further research exploring potential regional or geographic factors influencing early outcomes in acute HF.

As noted previously, the higher in-hospital mortality among dn-AHF patients likely reflects a more abrupt and severe presentation, frequently precipitated by acute ischemic events, which have been consistently associated with worse short-term outcomes in this population [7]. In contrast, patients with ad-CHF typically presented with predominantly congestive symptoms, consistent with a volume-overload phenotype that is generally more responsive to decongestive therapies such as diuretics [31, 33].

Interestingly, ad-CHF patients more frequently exhibited high-risk Stevenson profiles C and L, which are traditionally associated with worse outcomes in AHF; however, the dn-AHF group still demonstrated higher in-hospital mortality [26]. This apparent contradiction suggests that the prognostic utility of these hemodynamic profiles may be limited when distinguishing outcomes between dn-AHF and ad-CHF, highlighting that hemodynamic classification alone may not adequately capture short-term risk in this population.

Finally, male sex was associated with a lower risk of in-hospital mortality. Although this was not a primary focus of our analysis, the greater proportion of men in the ad-CHF group may have additionally contributed to its lower in-hospital mortality. The literature presents mixed evidence regarding sex-related prognostic differences in AHF: while several studies report better overall survival among women, often attributed to biological and hormonal cardioprotective mechanisms, others have described higher mortality among female patients, particularly in acute settings [19, 34]. Further investigations are warranted to determine whether the apparent protective effect of male sex in our study reflects a true biological difference or is instead driven by clinical and demographic heterogeneity within our population.

Social and clinical implications

Our findings have important clinical and social implications. The higher in-hospital mortality and complication rates observed in dn-AHF highlight the need for a more individualized approach from the moment of hospital admission. Early risk stratification could help mitigate adverse outcomes in this high-risk population. Moreover, identifying patients at greatest risk upon admission may optimize resource allocation and facilitate multidisciplinary interventions, ultimately reducing hospital complications and mortality. This underscores the importance of implementing early, phenotype-specific management protocols to improve outcomes, particularly in Latin American countries such as Colombia, where fragmented healthcare systems often hinder continuity of care and timely interventions, potentially exacerbating adverse outcomes in patients with AHF [35]. However, these findings should be interpreted in the context of certain methodological limitations, including the single-center design, the limited number of in-hospital events which restricted the complexity of the multivariable model, and the predominance of reduced LVEF in both groups, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Given this, and considering the distinctive disease profile in our region, future research should aim to validate these findings on a larger scale and to support the development of tailored management strategies for AHF patients in Latin America.

Strengths and limitations

This study provides valuable insights into the differences in in-hospital outcomes between dn-AHF and ad-CHF in a cohort from a Latin American country, a region where data on HF phenotypes remain relatively scarce. The use of real-world data from a high-complexity center strengthens the external validity of the findings, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of these patient populations. Additionally, the study includes a well-characterized cohort with a substantial sample size, enhancing the reliability of the results. The detailed assessment of in-hospital complications and mortality offers clinically relevant information to guide early risk stratification and management strategies. By highlighting differences in in-hospital outcomes between these two HF phenotypes, our findings contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting the need for tailored therapeutic approaches from the time of hospital admission.

Despite its strengths, this study has certain limitations. First, its observational design limits the ability to establish causal relationships. Additionally, although a multivariable model was constructed to adjust for potential confounders, the limited number of in-hospital deaths constrained the number of covariates that could be reliably included, increasing the risk of overfitting and reducing the statistical power to detect independent associations. Therefore, the results of the adjusted analysis should be interpreted with caution, as residual confounding cannot be ruled out. Data were collected from a single high-complexity institution in Colombia, which may affect the generalizability of the findings to other healthcare settings, particularly lower complexity centers, as well as other countries. Moreover, some characteristics of our population, particularly the predominance of reduced LVEF in both groups, limit the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, the reliance on electronic medical records may introduce information bias due to missing or incomplete documentation. Although missing data were generally limited, findings involving variables with incomplete information should be interpreted with caution. Certain variables that depend on patient recall may have further contributed to this limitation. Some variables such as valvular etiology were not specified by type or severity (e.g., rheumatic, degenerative), which limits the ability to assess their specific prognostic implications. Lastly, although the study spanned a 10-year period, we did not perform a time-stratified analysis, which may overlook clinically relevant differences in patient profiles, treatment practices, or outcomes that could have varied across different stages of the study period.

Conclusions

We observed that patients with dn-AHF had significantly higher in-hospital mortality and complication rates compared to those with ad-CHF, despite a lower comorbidity burden and no significant differences in ICU admission. This likely reflects a more abrupt, ischemia-driven presentation and the absence of prior hemodynamic adaptation or optimized therapy, leading to greater systemic compromise. In contrast, the congestive, volume-overload phenotype and higher male predominance in ad-CHF may partially explain its lower mortality. Early identification and proactive management of dn-AHF at hospital admission are crucial to improving outcomes in this high-risk population, particularly among patients with reduced ejection fraction. Further studies are warranted to validate these findings and guide phenotype-specific therapeutic strategies in AHF.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This study was conducted without financial support from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicting interests.

Informed Consent

The CEIB of FVL waived patient consent, as no interventions were intended for the participants, and all information was recorded from medical records. Additionally, the anonymity of all personal information was ensured.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: JEGM; data curation: YR, HOLG, ELR, and NO; Data analysis and interpretation: JDPM, DC, JM, SSM, YR, and HOLG; investigation: JDPM, DC, JM, SSM, DCC, JDLPDL, NAF, PO, and JEGM; methodology: JDPM, DC, JM, SSM, YR, HOLG, and JEGM; project administration: JEGM; supervision: JEGM; validation: JEGM; visualization: SSM; writing - original draft: JDPM, DC, JM, SSM, and JEGM; writing - review and editing: JDPM, DC, JM, SSM, YR, HOLG, DCC, JDLPDL, NAF, PO, ELR, NO and JEGM.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, Seferovic P, Rosano GMC, Coats AJS. Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2023;118(17):3272-3287.

doi pubmed - Fortich F, Ochoa Moron A, Balmaceda de La Cruz B, Renteria Roa J, Herrera Orego D, Gandara J, et al. Factores de riesgo para mortalidad en falla cardiaca aguda. Analisis de arbol de regresion y clasificacion. Rev Colomb Cardiol. 2020;27(1):20-28.

- Gonzalez-Pacheco H, Alvarez-Sangabriel A, Martinez-Sanchez C, Briseno-Cruz JL, Altamirano-Castillo A, Mendoza-Garcia S, Manzur-Sandoval D, et al. Clinical phenotypes, aetiologies, management, and mortality in acute heart failure: a single-institution study in Latin-America. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8(1):423-437.

doi pubmed - Gomez-Mesa JE, Saldarriaga C, Echeverria LE, Rivera-Toquica A, Luna P, Campbell S, Morales LN, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of heart failure patients from a middle-income country: the RECOLFACA registry. Glob Heart. 2022;17(1):57.

doi pubmed - Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, Deswal A, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(18):e895-e1032.

doi pubmed - Dunlay SM, Redfield MM, Weston SA, Therneau TM, Hall Long K, Shah ND, Roger VL. Hospitalizations after heart failure diagnosis a community perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(18):1695-1702.

doi pubmed - Raffaello WM, Henrina J, Huang I, Lim MA, Suciadi LP, Siswanto BB, Pranata R. Clinical characteristics of de novo heart failure and acute decompensated chronic heart failure: Are they distinctive phenotypes that contribute to different outcomes? Card Fail Rev. 2020;7:e02.

doi pubmed - Xanthopoulos A, Butler J, Parissis J, Polyzogopoulou E, Skoularigis J, Triposkiadis F. Acutely decompensated versus acute heart failure: two different entities. Heart Fail Rev. 2020;25(6):907-916.

doi pubmed - Franco J, Formiga F, Corbella X, Conde-Martel A, Llacer P, Alvarez Rocha P, Ormaechea Gorricho G, et al. De novo acute heart failure: Clinical features and one-year mortality in the Spanish nationwide Registry of Acute Heart Failure. Med Clin (Barc). 2019;152(4):127-134.

doi pubmed - Pranata R, Tondas AE, Yonas E, Vania R, Yamin M, Chandra A, Siswanto BB. Differences in clinical characteristics and outcome of de novo heart failure compared to acutely decompensated chronic heart failure - systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Cardiol. 2021;76(4):410-420.

doi pubmed - Garcia Sarasola A, Alquezar Arbe A, Gil V, Martin-Sanchez FJ, Jacob J, Llorens P, Rizzi M, et al. NOVICA: Characteristics and outcomes of patients who have a first episode of heart failure (de novo). Rev Clin Esp (Barc). 2019;219(9):469-476.

doi pubmed - Lassus JP, Siirila-Waris K, Nieminen MS, Tolonen J, Tarvasmaki T, Peuhkurinen K, Melin J, et al. Long-term survival after hospitalization for acute heart failure—differences in prognosis of acutely decompensated chronic and new-onset acute heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(1):458-462.

doi pubmed - Carlos Andres Castaneda, Pablo Enrique Chapaarro, Karol Patricia Cotes, Diana Patricia Diaz, Sandra Patricia Salas. Mortalidad 1998-2011 y situacion de salud en los municipios de frontera terrestre en Colombia [Internet]. Instituto Nacional de Salud. 2013. (Observatorio Nacional de Salud). Report No.: Segundo Informe ONS: Available from: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/IA/INS/Segundo%20informe%20ONS.pdf.

- Gomez-Mesa JE, Saldarriaga CI, Echeverria LE, Luna P. Registro colombiano de falla cardiaca (RECOLFACA): metodologia y datos preliminares. Rev Colomb Cardiol. 2021 Jun;28(3):217-230.

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194.

doi pubmed - Younis A, Mulla W, Goldkorn R, Klempfner R, Peled Y, Arad M, Freimark D, et al. Differences in Mortality of New-Onset (De-Novo) acute heart failure versus acute decompensated chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124(4):554-559.

doi pubmed - Mulla W, Klempfner R, Natanzon S, Mazin I, Maizels L, Abu-Much A, Younis A. Female gender is associated with a worse prognosis amongst patients hospitalised for de-novo acute heart failure. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(4):e13902.

doi pubmed - Investigators GC, Joseph P, Roy A, Lonn E, Stork S, Floras J, Mielniczuk L, et al. Global variations in heart failure etiology, management, and outcomes. JAMA. 2023;329(19):1650-1661.

doi pubmed - Regitz-Zagrosek V. Sex and gender differences in heart failure. Int J Heart Fail. 2020;2(3):157-181.

doi pubmed - Wei S, Miranda JJ, Mamas MA, Zuhlke LJ, Kontopantelis E, Thabane L, Van Spall HGC. Sex differences in the etiology and burden of heart failure across country income level: analysis of 204 countries and territories 1990-2019. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2023;9(7):662-672.

doi pubmed - Teerlink JR, Alburikan K, Metra M, Rodgers JE. Acute decompensated heart failure update. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2015;11(1):53-62.

doi pubmed - Tromp J, Teng TK. Regional differences in the epidemiology of heart failure. Korean Circ J. 2024;54(10):591-602.

doi pubmed - Gerhardt T, Gerhardt LMS, Ouwerkerk W, Roth GA, Dickstein K, Collins SP, Cleland JGF, et al. Multimorbidity in patients with acute heart failure across world regions and country income levels (REPORT-HF): a prospective, multicentre, global cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(12):e1874-e1884.

doi pubmed - Gomez KA, Tromp J, Figarska SM, Beldhuis IE, Cotter G, Davison BA, Felker GM, et al. Distinct comorbidity clusters in patients with acute heart failure: data from RELAX-AHF-2. JACC Heart Fail. 2024;12(10):1762-1774.

doi pubmed - Naffaa ME, Nasser R, Manassa E, Younis M, Azzam ZS, Aronson D. Cardiac troponin-I as a predictor of mortality in patients with first episode acute atrial fibrillation. QJM. 2017;110(8):507-511.

doi pubmed - Palazzuoli A, Ruocco G, Valente S, Stefanini A, Carluccio E, Ambrosio G. Non-invasive assessment of acute heart failure by Stevenson classification: Does echocardiographic examination recognize different phenotypes? Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:911578.

doi pubmed - Lippi G, Sanchis-Gomar F. Global epidemiology and future trends of heart failure. AME Med J [Internet]. 2020;5(0). [cited Aug 10, 2024] Available from: https://amj.amegroups.org/article/view/5475.

- Alberto C, Moises RM, Vicente BG, Jose M. GA, Aurora B, Rosa AB. Insuficiencia cardiaca de novo tras un sindrome coronario agudo en pacientes sin insuficiencia cardiaca ni disfuncion ventricular izquierda. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2021;74(6):494-501.

- Quien M, Bae JY, Jang SJ, Davila C. Short term outcomes and resource utilization in de-novo versus acute on chronic heart failure related cardiogenic shock: a nationwide analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1454884.

doi pubmed - Guarracino F, Zima E, Pollesello P, Masip J. Short-term treatments for acute cardiac care: inotropes and inodilators. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2020;22(Suppl D):D3-D11.

doi pubmed - Bhatt AS, Berg DD, Bohula EA, Alviar CL, Baird-Zars VM, Barnett CF, Burke JA, et al. De novo vs acute-on-chronic presentations of heart failure-related cardiogenic shock: insights from the critical care cardiology trials network registry. J Card Fail. 2021;27(10):1073-1081.

doi pubmed - Badawy L, Ta Anyu A, Sadler M, Shamsi A, Simmons H, Albarjas M, Piper S, et al. Long-term outcomes of hospitalised patients with de novo and acute decompensated heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2025;425:133061.

doi pubmed - Faselis C, Arundel C, Patel S, Lam PH, Gottlieb SS, Zile MR, Deedwania P, et al. Loop diuretic prescription and 30-day outcomes in older patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(6):669-679.

doi pubmed - Nozaki A, Shirakabe A, Hata N, Kobayashi N, Okazaki H, Matsushita M, Shibata Y, et al. The prognostic impact of gender in patients with acute heart failure - An evaluation of the age of female patients with severely decompensated acute heart failure. J Cardiol. 2017;70(3):255-262.

doi pubmed - Ruano AL, Rodriguez D, Rossi PG, Maceira D. Understanding inequities in health and health systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: a thematic series. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):94.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cardiology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.