| Cardiology Research, ISSN 1923-2829 print, 1923-2837 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cardiol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cr.elmerpub.com |

Short Communication

Volume 16, Number 5, October 2025, pages 453-456

Transfer and Survival of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Medicare Patients

Michelle Leeberga, Andrew Shermeyerb, Michael J. Wardc, d, e, Beth Virnigf, Julian Wolfsona, Caitlin Carrollb, Sayeh Nikpayb, g

aDivision of Biostatistics and Health Data Science, University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, MN, USA

bDivision of Health Policy and Management, University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, MN, USA

cDepartment of Emergency Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA

dGeriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center, Tennessee Valley Healthcare Center, Nashville, TN, USA

eDepartment of Biomedical Informatics, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA

fCollege of Public Health and Health Professions, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

gCorresponding Author: Sayeh Nikpay, Division of Health Policy and Management, University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA

Manuscript submitted September 12, 2025, accepted September 26, 2025, published online October 10, 2025

Short title: Transfer and Survival of STEMI Medicare Patients

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cr2143

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Interhospital transfer of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients can lead to greater access to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and reduce mortality. However, it is unclear how the characteristics of the transferring and receiving hospitals impacts mortality of transferred STEMI patients.

Methods: In this retrospective cohort study, we estimated differences in mortality among STEMI patients undergoing interhospital transfer using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and adjusted hazard ratios derived from Cox proportional hazard models.

Results: We found that partial PCI capability (i.e., retaining some patients while transferring others for PCI) of the transferring hospital and lower quality of the receiving hospital were associated with lower survival.

Conclusions: Interhospital transfers driven by factors other than distance and quality can negatively affect patient outcomes.

Keywords: STEMI; Interhospital transfer; Medicare; Rural hospitals

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Ten percent of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) die within 30 days, but timely percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) can reduce mortality [1]. Interhospital transfers have been associated with greater access to PCI and lower 30-day mortality for STEMI patients [2]. Existing studies suggest that interhospital transfer decisions depend on a variety of factors including PCI capabilities of the transferring hospital [3], quality of receiving hospitals [4], and financial relationships between hospitals [5], such as system status.

In this study, we estimated differences in mortality among STEMI patients undergoing interhospital transfer, based on the characteristics of the transferring and receiving hospitals.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Minnesota (IRB ID: STUDY00011056). This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible institution on human subjects as well as with the Helsinki Declaration.

We identified hospital stays in 100% fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare inpatient and outpatient data (2011 - 2020) for patients with 12 months of preceding FFS coverage, non-follow-up, and a primary, secondary, or tertiary diagnosis code for STEMI. We identified interhospital transfers following validated methods [6]. We defined three types of hospitals: non-PCI capable transferring hospitals, which only transferred STEMI patients; partially PCI-capable transferring hospitals, which both transferred and received STEMI patients; and receiving hospitals, which only received transferred STEMI patients. We assessed system membership and rural location using American Hospital Association data and 30-day risk adjusted acute myocardial infarction (AMI) mortality rates of receiving hospitals using Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Hospital Compare data.

Our primary outcome was time-to-death from the start of the hospital stay through 1 year. Explanatory variables included PCI capability, rural location, and system status of the transferring hospital, and decile of receiving hospital quality. We present Kaplan-Meier survival curves and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) from Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for patient sex, age, and Elixhauser comorbidity index, and year. We performed sensitivity analyses limiting to patients who ultimately received PCI after transfer. All analyses were performed using R 4.0.4.

Our final analytic sample included 56,489 patients undergoing transfer. Seventeen percent were transferred from a partially PCI capable hospital, 62% were transferred from a system-member hospital, and 69% were transferred from a rural hospital. Quality of the receiving hospital was in the fifth decile on average. The average patient was 76 years old, had 3.0 comorbidities, and was more likely to be male.

| Results | ▴Top |

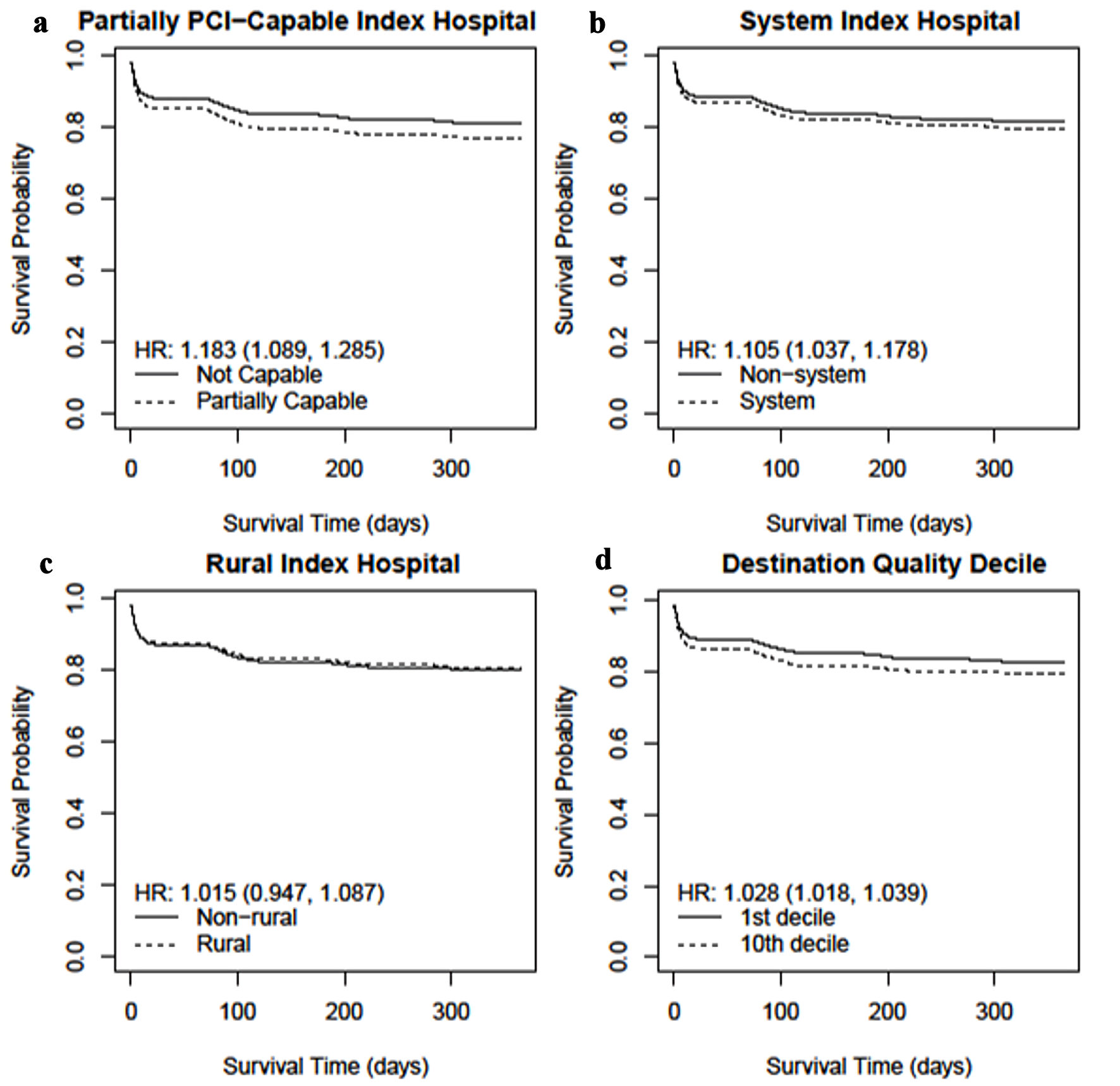

The adjusted HR for partial PCI capability of the transferring hospital was 1.18 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.09 - 1.29) (Fig. 1). The adjusted HR for system status of the transferring hospital was 1.11 (95% CI: 1.04 - 1.18). The adjusted HR for rural status of the transferring hospital was 1.02 (95% CI: 0.95 - 1.09). Finally, the adjusted HR for 30-day AMI mortality decile of the receiving hospital was 1.028 (95% CI: 1.017 - 1.039).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Estimated Kaplan-Meier survival curves and estimated Cox proportional hazard ratios (HRs) by characteristics of transferring and receiving hospitals (2011 - 2020). Source: 100% FFS Medicare Claims, 2011 - 2020. The figure displays the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for STEMI patients who were transferred during a hospital stay. (a) Comparison of survival for patients transferred from PCI-capable and non-PCI-capable hospitals. (b) Comparison of survival for patients transferred from system and non-system hospitals. (c) Comparison of survival for patients transferred from rural and non-rural hospitals. (d) Comparison of survival for patients transferred to hospitals in the bottom and top deciles of 30-day risk-adjusted mortality among acute myocardial infarction patients. Each panel also shows the estimated adjusted HRs and 95% confidence intervals. HRs are adjusted for patient sex, age, Elixhauser comorbidity count, and a set of indicators for the year in which the stay occurred. FFS: fee-for-service; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. |

Restricting to patients who received PCI (n = 30,342), results were qualitatively similar except for system status (HR = 1.10; 95% CI: 0.98 - 1.24). The adjusted HRs for partial PCI capability (HR = 1.29; 95% CI: 1.11 - 1.49), rural status (HR = 1.01; 95% CI: 0.89 - 1.14), and destination hospital quality (HR = 1.04; 95% CI: 1.02 - 1.06) were similar to the primary analysis.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Among Medicare STEMI patients undergoing interhospital transfers, partial PCI capability of the transferring hospital and lower quality of the receiving hospital were associated with lower survival. These results suggest that patient outcomes could be worsened when interhospital transfer is driven by factors other than distance and quality. However, some statistically significant associations were not clinically meaningful.

Technological advances like PCI have made medical treatment more effective but also more complex, leading to large benefits from being treated at a high-volume, specialized hospitals and drawing patients away from smaller, lower-resource hospitals. Our results are consistent with this dynamic, given the survival advantage of patients transferred to high-quality hospitals and the relatively high survival rates of patients who were transferred away from non-PCI hospitals. This dynamic raises several avenues for policymaking. First, it is crucial that non-PCI hospitals can create transfer relationships with high-quality PCI hospitals. One option for incentivizing transfer relationships is regionalization of care [7]. Second, consolidation of care into fewer, specialized hospitals will draw patients and revenues away from smaller hospitals, which are already struggling with financial distress. Policymakers could consider financial models that support limited service at smaller hospitals, as in the Rural Emergency Hospital program. Policymakers could also consider options for antitrust policy, since consolidating care into a smaller number of specialized hospitals may give those hospitals increased market power to negotiate higher commercial prices.

Limitations

Our study had a number of limitations. First, our study may be limited because we cannot ascertain why STEMI patients are transferred from partially PCI-capable hospitals, which could include transient lack of availability of PCI, unobserved clinical complexity or clinician or patient preference. Moreover, our results are limited since we were unable to assess acute clinical severity of the infarction nor the comprehensive medical characteristics of the patient using the FFS Medicare data, which may also have impacted transfer decisions. While we controlled for patient characteristics using the Elixhauser comorbidity index, this was a summary measure rather than a comprehensive one.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented at the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine conference in May 2024 and at the American Public Health Association annual meeting in October 2024.

Financial Disclosure

This work was supported by a grant from the National Heart Lung and Blood Disorders Institute (1R01HL153179-01A1).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Informed Consent

The University of Minnesota IRB issued a waiver of the consent process because: 1) the research involved no more than minimal risk to the subjects; 2) the waiver would not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the subjects; and 3) the research could not be practicably carried out without the waiver.

Author Contributions

Dr. Nikpay, Dr. Virnig, and Dr. Leeberg designed the study. Dr. Nikpay, Dr. Virnig, Dr. Ward, Dr. Carroll, Mr. Shermeyer, and Dr. Leeberg discussed interpretation of the result. Dr. Nikpay, Dr. Virnig, Dr. Leeberg and Mr. Shermeyer drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; IRB: institutional review board; FFS: fee-for-service

| References | ▴Top |

- Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119-177.

doi pubmed - De Luca G, Biondi-Zoccai G, Marino P. Transferring patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction for mechanical reperfusion: a meta-regression analysis of randomized trials. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52(6):665-676.

doi pubmed - Lin S, Shermeyer A, Nikpay S, Hsia RY, Ward MJ. Initial treatment of uninsured patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction by facility percutaneous coronary intervention capabilities. Acad Emerg Med. 2024;31(2):119-128.

doi pubmed - Iwashyna TJ, Kahn JM, Hayward RA, Nallamothu BK. Interhospital transfers among Medicare beneficiaries admitted for acute myocardial infarction at nonrevascularization hospitals. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(5):468-475.

doi pubmed - Veinot TC, Bosk EA, Unnikrishnan KP, Iwashyna TJ. Revenue, relationships and routines: the social organization of acute myocardial infarction patient transfers in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(10):1800-1810.

doi pubmed - Nikpay S, Leeberg M, Kozhimannil K, Ward M, Wolfson J, Graves J, Virnig BA. A proposed method for identifying Interfacility transfers in Medicare claims data. Health Serv Res. 2025;60(1):e14367.

doi pubmed - Feazel L, Schlichting AB, Bell GR, Shane DM, Ahmed A, Faine B, Nugent A, et al. Achieving regionalization through rural interhospital transfer. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(9):1288-1296.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cardiology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.