| Cardiology Research, ISSN 1923-2829 print, 1923-2837 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cardiol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cr.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 15, Number 6, December 2024, pages 472-476

The Mechanism and Management of Pneumopericardium Caused by Right Ventricular Lead Perforation

Tomo Komakia, c, Yuuki Uenoa, Noriyuki Mohria, Akihito Ideishia, Kohei Tashiroa, Shin-ichiro Miuraa, Masahiro Ogawaa, b

aDepartment of Cardiology, Fukuoka University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan

bDepartment of Clinical Laboratory Medicine, Fukuoka University Faculty of Medicine, Fukuoka, Japan

cCorresponding Author: Tomo Komaki, Department of Cardiology, Fukuoka University Hospital, Jonan-ku, Fukuoka 814-0180 Japan

Manuscript submitted October 16, 2024, accepted November 5, 2024, published online December 3, 2024

Short title: Pneumopericardium Caused by RV Lead Perforation

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cr1738

| Abstract | ▴Top |

An 83-year-old man underwent dual-chamber pacemaker placement for complete atrioventricular block at another hospital. The active-fixation ventricular lead was positioned on the free wall of the anterior right ventricle. Ventricular pacing failure occurred on the day after pacemaker implantation, and fluoroscopy revealed right ventricular (RV) lead perforation. The patient was transferred to our hospital, and chest computed tomography revealed a severe pneumothorax and moderate pneumopericardium. These symptoms were relieved after chest tube drainage, and the patient’s hemodynamics stabilized. The RV lead was percutaneously removed using simple traction under fluoroscopic guidance with cardiac surgical backup and was uneventfully refixed to the RV septum. Although there have been several reports of pneumopericardium caused by atrial lead perforation, there are very few cases related to RV lead. Pneumopericardium complicated by pneumothorax due to RV lead perforation can be relieved using chest tube drainage without the need for pericardiocentesis.

Keywords: Cardiac implantable electronic device; Right ventricular lead perforation; Pneumopericardium; Pneumothorax; Chest tube drainage

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cardiac implantable electronic devices, including pacemakers (PMs), implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), and cardiac resynchronization therapy, have become the mainstay therapy for many cardiac conditions [1]. The Japan Arrhythmia Device Industry Association reported that cardiac implantable electronic devices were implanted in approximately 54,000 patients in 2023, and the need for such devices is increasing every year. Although PM implantation is usually considered safe, it can be associated with potential complications, such as pocket hematoma, infection, lead dislodgement, pneumothorax, and cardiac tamponade [2]. Pneumopericardium due to lead perforation is an extremely rare complication reported in only a few case reports [3-5]. Most patients are asymptomatic; however, in rare cases, they can progress to tension pneumopericardium and cardiac tamponade. Pneumothorax often occurs simultaneously, which may confuse clinicians when resolving the conditions. Most reported cases of pneumopericardium due to lead perforation are caused by active-fixation atrial leads, and, to our knowledge, there have been few reports on right ventricular (RV) lead perforation. Herein, we report a case of RV lead perforation complicated by pneumothorax and pneumopericardium that led to obstructive shock. We also discuss the mechanisms and management of pneumopericardium caused by RV lead perforation.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

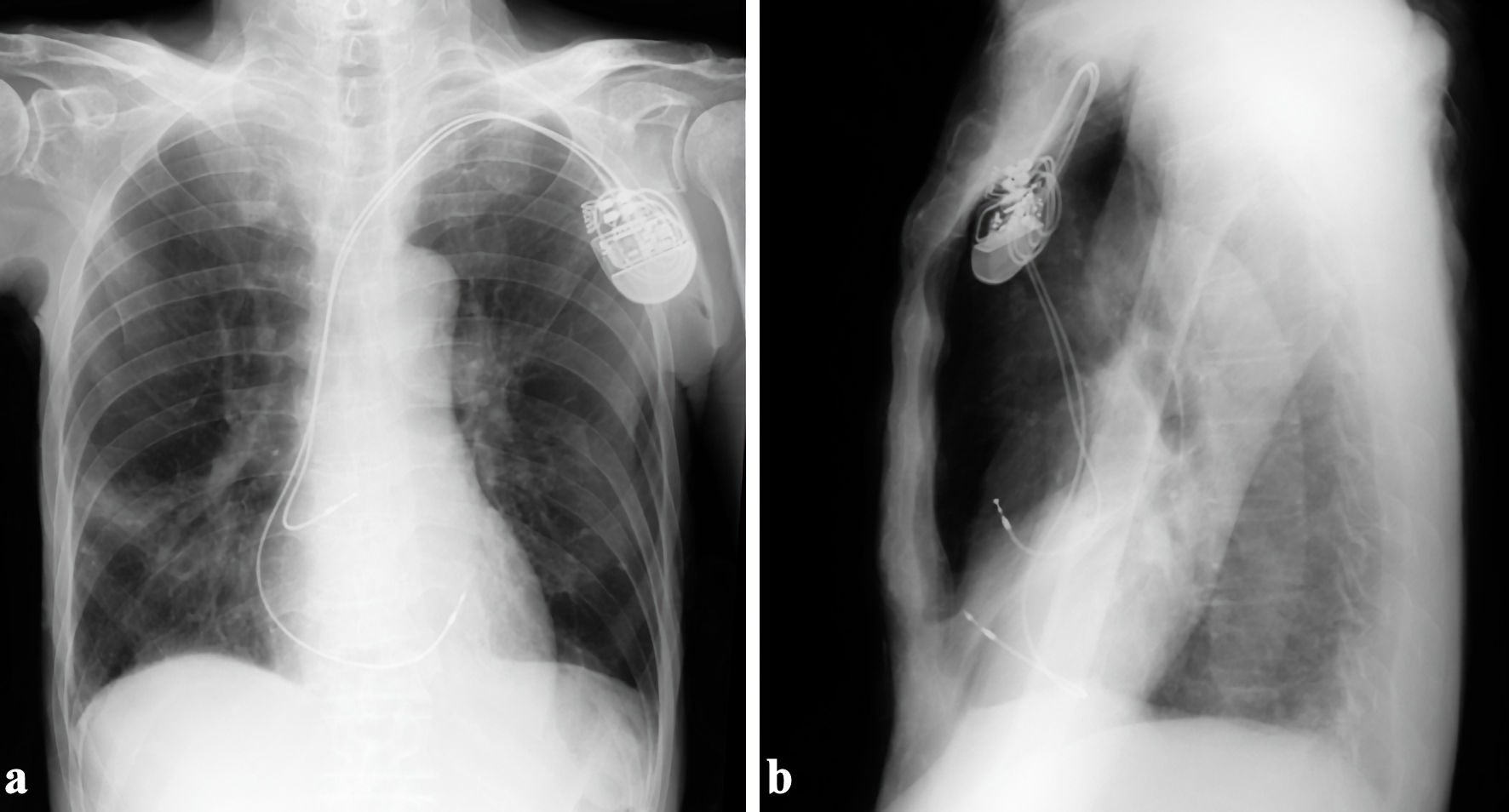

An 83-year-old man presented with a history of hypertension and Parkinson’s disease. He had bradycardia and hypotension while using daycare services. His body mass index was 16.7 kg/m2, categorizing him as underweight. The patient did not receive any antithrombotic drugs. He was transferred to a nearby hospital, and a 12-lead electrocardiogram showed a complete atrioventricular block with a heart rate of 35 beats per minute. Echocardiography did not reveal any abnormal regional wall motion of the left ventricle, and the ejection fraction was preserved at 73%. Emergent coronary angiography revealed no significant stenosis. A temporary transvenous pacing lead was placed at the RV apex, and a dual-chamber PM (ACCOLADE™ MRI L311, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) was implanted from the left precordium. Active-fixation atrial and ventricular leads (Ingevity™+, 7736 with a length of 52 cm, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA and Ingevity™+, 7842 with a length of 59 cm, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA, respectively) were placed in the right atrial appendage and anterior RV free wall, respectively. Chest radiography performed immediately after PM implantation showed normal lead position, with no pneumothorax or pneumopericardium, and consolidation in the right middle lung field (Fig. 1). The ventricular lead parameters were normal with a pacing threshold of 0.6 V at 0.5 ms and impedance of 752 Ω. In the following day after PM implantation, he developed wet cough and a fever of 38 °C. In the afternoon, ventricular pacing failure occurred, and the ventricular lead pacing threshold increased to 3.5 V at 0.5 ms. As there was no change in the position of the RV lead tip on the chest radiograph, the pacing output was temporarily changed to 7 V at 0.5 ms. However, ventricular pacing failure recurred several hours later, and a temporary transvenous pacing lead was reinserted under fluoroscopy. At this time, the RV lead tip advanced and protruded from the cardiac silhouette.

Click for large image | Figure 1. The ventricular active-fixation lead was placed in the anterior right ventricular free wall. (a) Anteroposterior view. (b) Right-left view. |

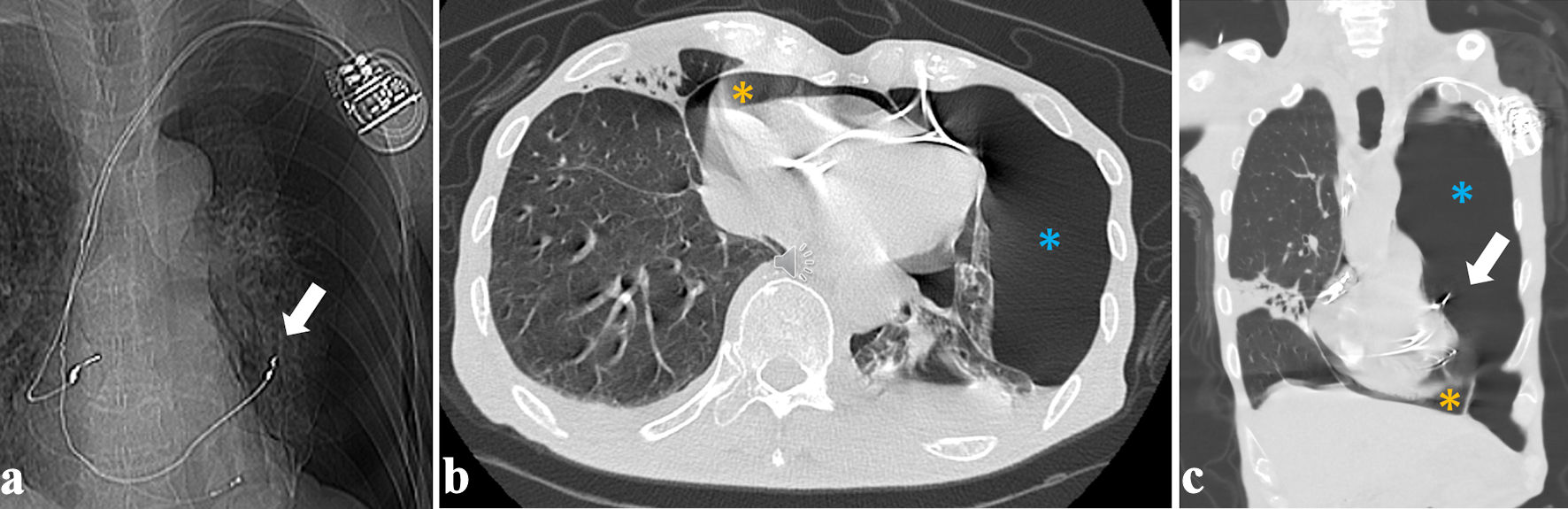

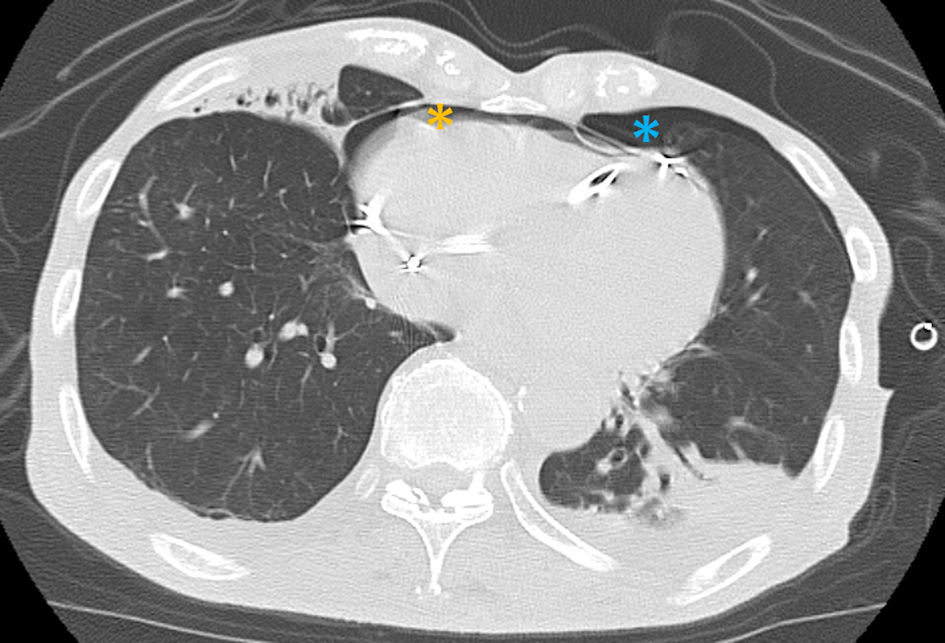

The patient was diagnosed with RV lead perforation and was transferred to our hospital on the second day after PM implantation. On arrival, the patient’s consciousness was clouded, and his vital signs were as follows: pulse rate: 80/min under ventricular pacing, peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) 93% under the administration of oxygen at 3 L/min, and blood pressure of 63/41 mm Hg. Physical examination revealed decreased breathing sounds in the left lung field, coarse crackles in the right lung field, and a distended jugular vein. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed that the RV lead had advanced into the left thoracic cavity, with severe pneumothorax and moderate pneumopericardium anteriorly, approximately 2 cm thick, in addition to bilateral pleural effusion and right middle-lobe pneumonia (Fig. 2). As the combination of pneumothorax and pneumopericardium caused obstructive shock, a 24-Fr chest tube was urgently inserted into the left thoracic cavity from the left fifth intercostal space. In addition, the albumin preparation and extracellular fluid were administered at full speed. The patient recovered gradually after chest tube drainage and volume resuscitation. Repeated CT 2 h after chest tube insertion showed improvement of the left pneumothorax and pneumopericardium (Fig. 3). Laboratory tests revealed that renal and liver functions were within the normal range, whereas white blood cell count (10,600/µL), C-reactive protein (14.8 mg/dL) level, brain natriuretic peptide level (324 pg/mL), and troponin-I level (83.9 pg/mL) were elevated.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Right ventricular lead tip protruding into the left thoracic cavity ((a, c), white arrows), with moderate pneumopericardium and left severe pneumothorax, respectively ((b, c), orange and blue asterisks). (a) Scout image. (b) Axial image. (c) Coronal image. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Both left pneumothorax (orange asterisk) and pneumopericardium (blue asterisk) were relieved 2 h after chest tube drainage. |

We planned to remove the RV lead percutaneously using simple traction with a cardiac surgeon on standby. The procedure was performed under general anesthesia in the operating room with transesophageal echocardiography and hemodynamic monitoring. After the lead helix was unscrewed under fluoroscopic guidance, it was removed percutaneously using simple traction. After RV lead removal, no pericardial fluid was observed, with stable hemodynamics. The existing lead was repositioned to the RV septum using a site-selective pacing catheter 3 (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA).

The postoperative course was uneventful, without retention of pericardial fluid, and there was no recurrence of pneumothorax or pneumopericardium after removal of the chest tube. Chest radiography performed 1 month after repositioning of the RV lead showed a normal lead position and no recurrence of pneumothorax or pneumopericardium (Fig. 4).

Click for large image | Figure 4. There was no recurrence of pneumothorax and pneumopericardium 1 month after repositioning of the right ventricular lead. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Pneumopericardium due to lead perforation is an extremely rare complication, and most cases are asymptomatic; however, in rare cases, it can progress to tension pneumopericardium.

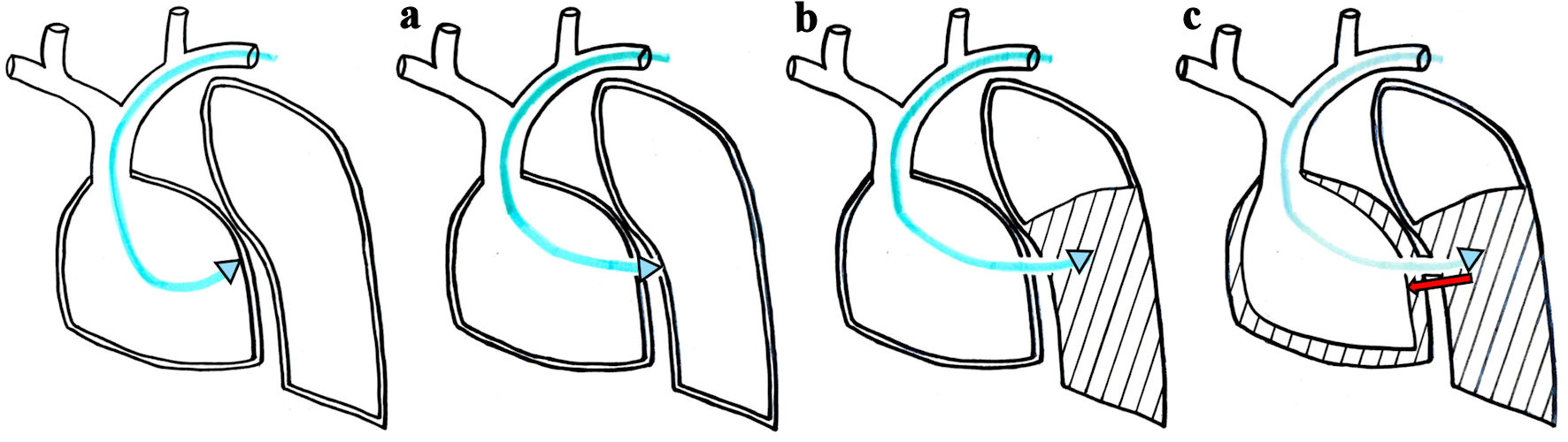

The mechanism of pneumopericardium caused by RV lead perforation is shown in Figure 5. When the ventricular lead was positioned at the RV free wall, it sequentially perforated the right ventricle, pericardium, left pleura, and lung, resulting in a left pneumothorax (Fig. 5a, b). As a result of the increased intrathoracic pressure due to the pneumothorax, the air in the thoracic cavity tracked into the pericardial cavity through the pericardium-pleural fistula, resulting in a pneumopericardium (Fig. 5c). Based on the above mechanism, pneumopericardium caused by RV lead perforation was complicated by left pneumothorax, both of which may cause hemodynamic collapse. Chest tube drainage relieved both pneumothorax and pneumopericardium because it can drain intrathoracic and pericardial air through the pleura and the pericardium-pleural fistula. Therefore, the first aid for pneumopericardium due to RV lead perforation is not pericardiocentesis, but chest tube drainage. Although the patient experienced obstructive shock due to severe pneumothorax and moderate pneumopericardium, his hemodynamics gradually improved after chest tube drainage and volume resuscitation.

Click for large image | Figure 5. The active-fixation ventricular lead sequentially perforates the right ventricular free wall, pericardium, left pleura and lung, resulting in left pneumothorax (a, b). Intrathoracic air then tracks into the pericardial cavity through the pericardium-pleural fistula (red arrow), resulting in pneumopericardium (c). |

Second, the management of RV lead perforation centers around whether to remove the perforating lead, either percutaneously or surgically, or to leave it in place. Regarding removal of the causative lead, conservative treatment is reported to be acceptable in patients with extrusion of the lead helix alone and satisfactory lead parameters [1, 6, 7]. However, lead removal and repositioning are necessary in cases with obvious extrusion of the lead and abnormal lead parameters, because there is a chance that it will perforate the surrounding structures over time. Laborderie et al [8] and Migliore et al [9] reported that percutaneous removal of RV and ICD leads is a safe and effective approach for patients with ventricular lead perforation. Because the right heart is a low-pressure system, perforation may be sealed by the myocardium “self-sealing” properties including muscle contraction and fibrosis, resulting in no sequela [10]. However, there are rare cases where significant bleeding in the pericardium followed by cardiac tamponade occurs immediately after lead removal; therefore, it is important to create an environment where pericardiocentesis and open thoracotomy repair can be performed promptly. Because this patient was not taking antithrombotic drugs and was in poor general condition with concomitant pneumonia, we planned for lead percutaneous removal, with precautions. The RV lead was removed without complications, and the postoperative course was uneventful.

Third, cardiac perforation in this case may have been influenced by low body mass index, advanced age, and temporary pacing, which have been reported to be risk factors for cardiac perforation [11]. However, the main cause was the fixation of the ventricular lead in the anterior RV free wall. Because the size of the right ventricle varies in each patient depending on their body type and underlying heart disease, it is difficult to accurately grasp the RV anatomy under fluoroscopic guidance alone. In this case, the ventricular lead was probably placed on the RV septum but was inadvertently positioned on the anterior RV free wall. In recent years, delivery catheters produced by different manufacturers have been used with conduction system pacing [12], which allows accurate identification of the RV septum using contrast injection from the catheter tip. Both fluoroscopic and angiographic guidance using such delivery catheters make it possible to avoid placing a lead in the RV free wall. Although pneumopericardium due to RV lead perforation is an extremely rare complication, the implanting physician needs to be aware of its risks and employ techniques such as pacing the septum rather than the free wall or apex to minimize perforation risk.

Finally, there have been several reports of pneumopericardium due to atrial lead perforation; however, RV lead perforation is extremely rare. As far as our investigation, the temporary ventricular pacing was reported to cause pneumopericardium by the RV perforation once before [13]. As the thickness of the RV wall averages 4 - 5 mm compared with that of the right atrial wall, which averages 2 mm, the incidence of lead perforation is generally reported to be lower with ventricular leads than with atrial leads [10]. There are few reports of pneumopericardium due to RV leads because pneumopericardium due to lead perforation itself is very rare, and the ventricular leads are less likely to perforate the myocardium than the atrial leads, as mentioned above. As the possible mechanisms are similar for both atrial and ventricular lead perforations, there is no significant difference in their management.

In conclusion, pneumopericardium caused by RV lead perforation is an extremely rare complication that can progress to tension pneumopericardium and cardiac tamponade. Pneumopericardium complicated by pneumothorax can be relieved with chest tube drainage, without the need for pericardiocentesis. To prevent RV lead perforation, the implanting physician needs to apply techniques to accurately place the ventricular lead in the RV septum and not in the RV free wall or apex.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Author Contributions

TK, YU, NM, AI, KT, SM, and MO contributed to the study design, and drafting, editing, and final approval of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available in this article.

Abbreviations

CT: computed tomography; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PM: pacemaker; RV: right ventricle

| References | ▴Top |

- Lo SW, Chen JY. Case report: A rare complication after the implantation of a cardiac implantable electronic device: Contralateral pneumothorax with pneumopericardium and pneumomediastinum. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:938735.

doi pubmed - Nantsupawat T, Li JM, Benditt DG, Adabag S. Contralateral pneumothorax and pneumopericardium after dual-chamber pacemaker implantation: Mechanism, diagnosis, and treatment. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2018;4(6):256-259.

doi pubmed - O'Neill R, Silver M, Khorfan F. Pneumopericardium with cardiac tamponade as a complication of cardiac pacemaker insertion one year after procedure. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(4):641-644.

doi pubmed - Hegwood E, Burkman G, Maheshwari A. Risk for contralateral pneumothorax, pneumopericardium, and pneumomediastinum in the elderly patient receiving a dual-chamber pacemaker-A case report of 2 patients with acute and chronic atrial lead perforation. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2023;9(9):680-684.

doi pubmed - Futami M, Komaki T, Arinaga T, Morii J, Sugihara M, Ogawa M, Miura SI. Postural conversion computed tomography for the diagnosis of pneumopericardium due to perforation by the active atrial lead. Intern Med. 2020;59(4):541-544.

doi pubmed - Sebastian CC, Wu WC, Shafer M, Choudhary G, Patel PM. Pneumopericardium and pneumothorax after permanent pacemaker implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28(5):466-468.

doi pubmed - Rehman WU, Muneeb A, Sakhawat U, Ganesh P, Braiteh N, Skovira V, Sajjad W, et al. A case of contralateral pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and pneumopericardium after dual-chamber pacemaker implantation. Case Rep Cardiol. 2022;2022:4295247.

doi pubmed - Laborderie J, Barandon L, Ploux S, Deplagne A, Mokrani B, Reuter S, Le Gal F, et al. Management of subacute and delayed right ventricular perforation with a pacing or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator lead. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102(10):1352-1355.

doi pubmed - Migliore F, Zorzi A, Bertaglia E, Leoni L, Siciliano M, De Lazzari M, Ignatiuk B, et al. Incidence, management, and prevention of right ventricular perforation by pacemaker and implantable cardioverter defibrillator leads. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014;37(12):1602-1609.

doi pubmed - Hirschl DA, Jain VR, Spindola-Franco H, Gross JN, Haramati LB. Prevalence and characterization of asymptomatic pacemaker and ICD lead perforation on CT. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30(1):28-32.

doi pubmed - Mahapatra S, Bybee KA, Bunch TJ, Espinosa RE, Sinak LJ, McGoon MD, Hayes DL. Incidence and predictors of cardiac perforation after permanent pacemaker placement. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2(9):907-911.

doi pubmed - Burri H, Vijayaraman P. A new era of physiologic cardiac pacing. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2023;25(Suppl G):G1-G3.

doi pubmed - Deanfield J, Jonathan A, Fox K. Pericardial complications of endocardial and epicardial pacing. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;283(6292):635-636.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cardiology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.