| Cardiology Research, ISSN 1923-2829 print, 1923-2837 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cardiol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cr.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 16, Number 3, June 2025, pages 289-294

Primary Cardiac Lymphoma Presenting With Sick Sinus Syndrome and Atrial Flutter

Tomo Komakia, b, c, e, Noriyuki Mohria, b, Akihito Ideishia, b, Takafumi Fujitab, Kohei Tashiroa, b, Tadaaki Arimurab, Kanta Fujimib, Yuta Nakashimad, Yasushi Takamatsud, Shin-ichiro Miurab, Masahiro Ogawaa, b, c

aThe Cardiac Arrhythmia Center and EP Laboratory, Fukuoka University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan

bDepartment of Cardiology, Fukuoka University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan

cDepartment of Clinical Laboratory Medicine, Fukuoka University Faculty of Medicine, Fukuoka, Japan

dDivision of Medical Oncology, Hematology and Infectious Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, Fukuoka University Faculty of Medicine, Fukuoka, Japan

eCorresponding Author: Tomo Komaki, Department of Clinical Laboratory Medicine, Fukuoka University Faculty of Medicine, Fukuoka 814-0180, Japan

Manuscript submitted April 11, 2025, accepted April 24, 2025, published online May 7, 2025

Short title: PCL Presenting With SSS and AFL

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cr2072

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Primary cardiac lymphoma is a rare, often fatal malignancy that can cause disorders of conduction depending on tumor location. We report two cases with sick sinus syndrome and atrial flutter secondary to primary cardiac lymphoma originating from the right atrium. One case required pacemaker implantation in the chronic phase after complete remission of lymphoma, and the other case in the acute phase when cardiac mass occupied the right atrium. Depending on the disease activity of lymphoma including its size, growth rate, and degree of invasion, the clinical course of sinus node dysfunction varies between each patient. In patients with conduction disorders, we suggest that long-term cardiac monitoring is necessary not only at onset but also after complete remission of lymphoma.

Keywords: Primary cardiac lymphoma; Sick sinus syndrome; Atrial flutter

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Sick sinus syndrome (SSS) is caused by degenerative fibrosis of the sinus node and surrounding atrial myocardium and is usually associated with aging. It is less often caused by infiltrative diseases, such as amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, scleroderma, hemochromatosis, and, rarely, cardiac tumors. Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL) is defined as non-Hodgkin lymphoma involving only the heart and/or pericardium (strict criterion) or as non-Hodgkin lymphoma presenting with cardiac manifestations, particularly when the bulk of the tumor is found in the heart (loose criterion) [1]. PCL is rare, accounting for 1.3% of primary cardiac tumors [2]. The majority of cases with PCL have diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs). PCL is often fatal, and its cardiac manifestations include heart failure, pleural and pericardial effusion, and life-threatening arrhythmia due to tumor invasion of the conduction system or myocardium. We report two cases presenting with SSS and atrial flutter (AFL) secondary to PCL originating from the right atrium (RA). One case required permanent pacemaker implantation (PMI) in the chronic phase after complete remission of lymphoma, and for the other case, in the acute phase when cardiac mass occupied the RA.

| Case Reports | ▴Top |

Case 1

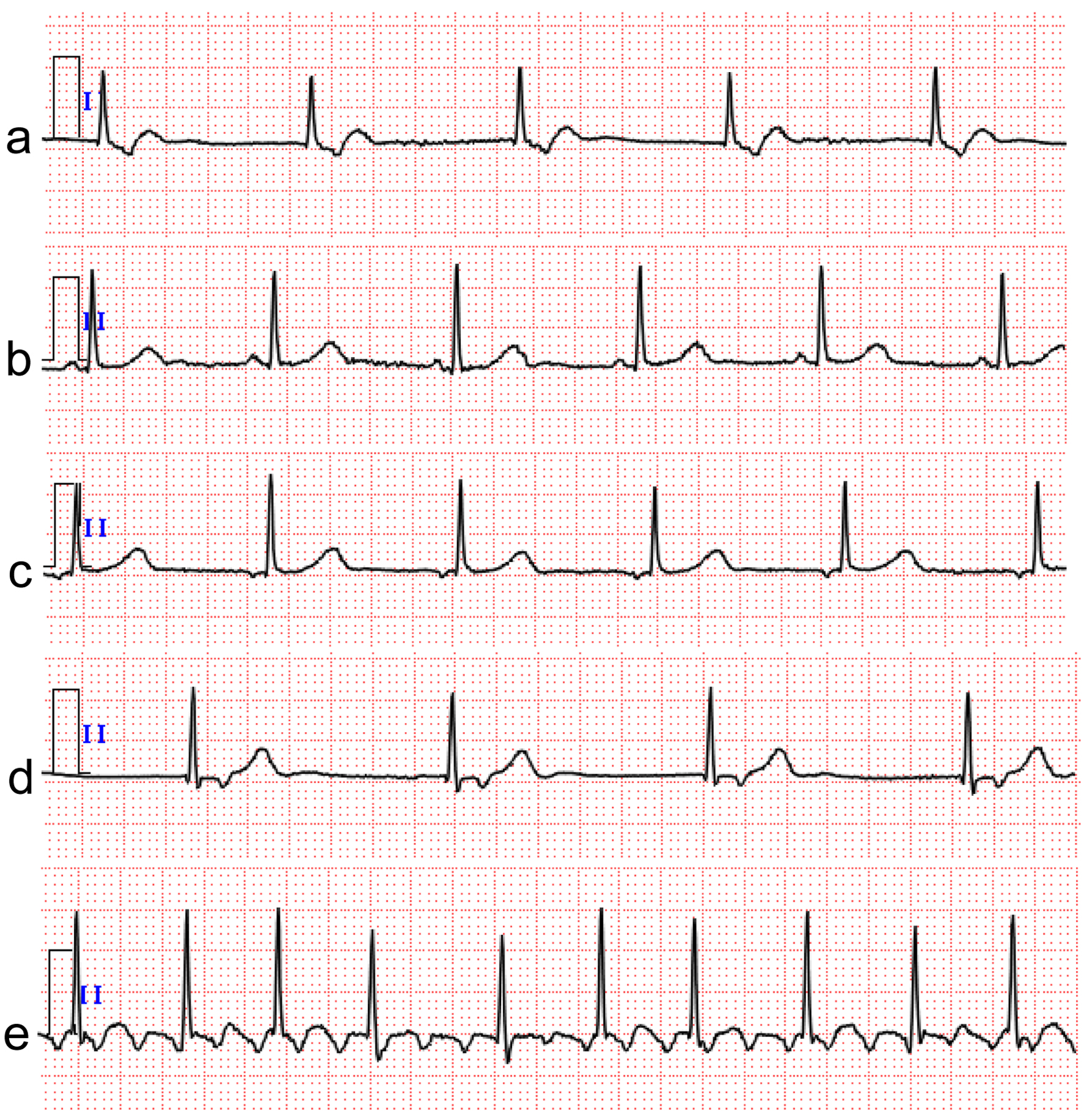

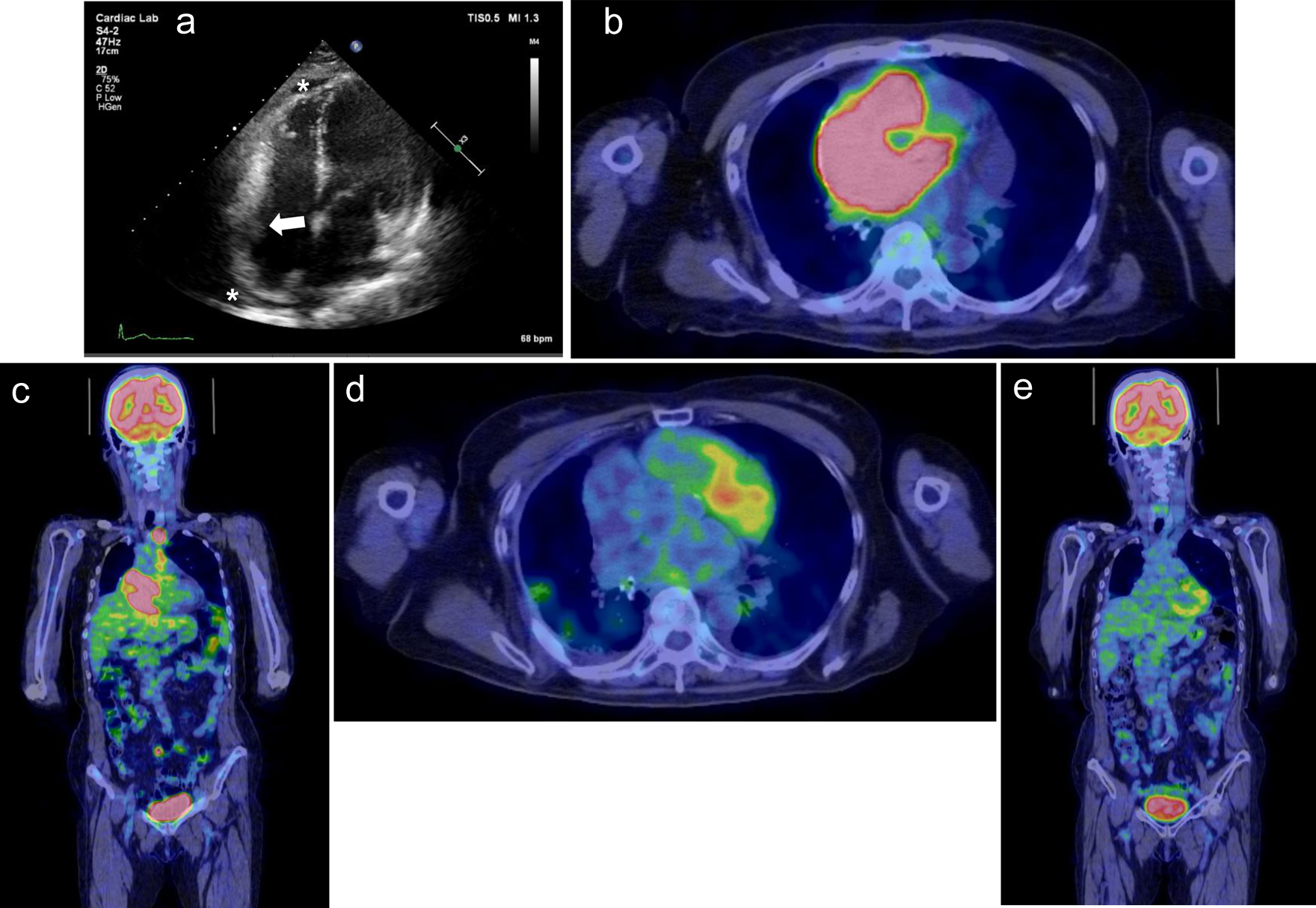

A 74-year-old woman had a history of hypertension and two lung resections for right lung cancer. One month prior to consultation, she noticed general fatigue, shortness of breath on exertion, and bilateral leg edema, which was treated with diuretics. She did not have night sweats or weight loss, but a few days prior to consultation, she had a fever of 38 °C for unknown reasons. At the time of consultation, her blood pressure was 121/79 mm Hg, pulse rate was 75 beats per minute, and SpO2 was maintained at 98% on room air. Physical examination revealed normal cardiac and lung sounds and no superficial lymphadenopathy. On blood examination, her white blood cell count was 4,100 cells/µL with no differential abnormalities, but anemia existed, with hemoglobin of 9.4 g/dL. Markers of inflammation and cell damage were elevated: C-reactive protein, 4.0 mg/dL (normal, 0 - 0.14 mg/dL), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), 360 U/L (normal, 124 - 222 U/L), and interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R), 6,356 U/mL (normal, 121 - 613 U/mL). Cardiac markers were also elevated: troponin I, 216 pg/mL (normal, < 30.0 pg/mL), and brain natriuretic peptide, 142 pg/mL (normal, ≤ 18.4 pg/mL). A 12-lead electrocardiogram did not show ST-T changes suggestive of ischemic heart disease, but junctional escape beats of 60 beats per minute were present (Fig. 1a). A chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly, and an echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular systolic function and a mass lesion in the right atrial free wall and slight pericardial effusion (Fig. 2a). The patient was admitted to our hospital to investigate the cardiac tumor. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed a widespread mass lesion extending from the superior vena cava (SVC) to the free wall of the RA, and 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography/CT (18F-FDG PET/CT) showed FDG accumulation in the anterior mediastinum, mesenteric lymph nodes, and right adrenal gland in addition to the RA (Fig. 2b, c). An anterior mediastinal lymph node biopsy revealed diffuse infiltration of large atypical lymphoid cells with distinct nucleoli, accompanied by patchy necrosis and many apoptotic bodies. DLBCL was diagnosed by immunohistochemical staining (activated B-cell subtype, CD20-positive, MUM1-positive, BCL6-positive, CD3-negative, CD5-negative, CD10-negative). As the finding of bone marrow aspiration was normal, Ann Arbor staging was classified as IVB. We started chemotherapy treatment with the combination of rituximab, pirarubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone (R-THP-COP). Pirarubicin was used in place of doxorubicin because pirarubicin is less cardiotoxic. After one cycle of R-THP-COP, echocardiography showed disappearance of the right atrial tumor and pericardial effusion, and the patient had normal sinus rhythm after receiving two cycles (Fig. 1b). After receiving five cycles, 18F-FDG PET/CT showed no FDG accumulation, indicating complete remission of lymphoma (Fig. 2d, e), but the patient developed an ectopic atrial rhythm (Fig. 1c). Because intermittent sinus bradycardia was observed during R-THP-COP, the chemotherapy was limited to five cycles. One year after initial chemotherapy, swelling of the left submandibular lymph node appeared, and recurrence of DLBCL was confirmed. The patient received three cycles of salvage chemotherapy with the combination of gemcitabine, carboplatin, and dexamethasone (GCD), followed by one cycle of GCD with rituximab. Because the DLBCL was refractory to GCD, the patient then received the next salvage chemotherapy with the combination of carboplatin, dexamethasone, etoposide, and irinotecan (CDE-11). After four cycles of CDE-11 (cycles 1-3 with rituximab and cycle 4 without it), the DLBCL was in complete remission. However, the patient’s cardiac rhythm deteriorated to junctional escape beats, which persisted without symptoms (Fig. 1d). Two years after the second complete remission of lymphoma, the patient developed congestive heart failure secondary to AFL (Fig. 1e). This AFL was considered to be the typical type based on the polarity of the sawtooth appearance of the flutter waves (negative polarity in inferior lead and positive polarity in anterior lead). A dual-chamber (DDD) pacemaker with atrial antitachycardia pacing was implanted from the left precordium. Approximately 2 years after PMI, the patient’s heart failure has been well controlled, and there has been no recurrence of DLBCL.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Case 1. Electrocardiogram results from admission to follow-up. (a) Junctional escape beats on admission. (b) Junctional escape beats returned to sinus rhythm after two cycles of initial chemotherapy. (c) Sinus rhythm deteriorated to ectopic atrial rhythm after five cycles of initial chemotherapy. (d) Ectopic atrial rhythm deteriorated to junctional escape beats again after four cycles of the second salvage chemotherapy. (e) Typical atrial flutter appeared 2 years after the second complete remission of lymphoma. The electrocardiogram was recorded at a calibration of 10 mm/mV and a speed of 25 mm/s. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Case 1. (a) Echocardiogram performed on admission shows mass lesions in the right atrial free wall (white arrow) and slight pericardial effusion (white asterisks). (b, c) 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) shows FDG accumulation in the anterior mediastinum, mesenteric lymph nodes, and right adrenal gland in addition to the right atrium. (d, e) After five cycles of initial chemotherapy, 18F-FDG PET/CT showed no FDG accumulation, indicating complete remission of lymphoma. |

Case 2

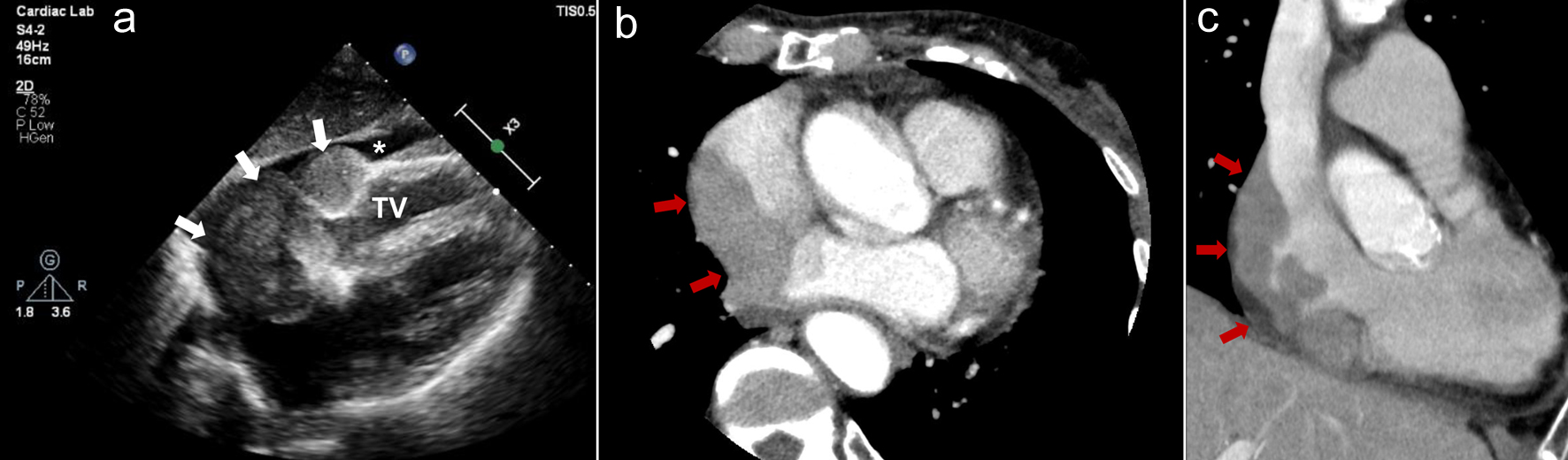

An 87-year-old woman had a history of an operation for right breast cancer at the age of 65 years. One month prior to consultation, she had experienced appetite loss followed by syncope. Holter electrocardiogram performed at a nearby hospital revealed sinus arrest up to 2.6 s. The patient was diagnosed with SSS and referred to our hospital. At the time of consultation, her blood pressure was 119/59 mm Hg, pulse rate was 86 beats per minute, SpO2 was maintained at 97% on room air, and she had a fever of 37.6 °C. Physical examination revealed normal cardiac and lung sounds and no superficial lymphadenopathy. On blood examination, her white blood cell count was 4,700 cells/µL with no differential abnormalities, but anemia existed, with hemoglobin of 10.5 g/dL. Markers of cell damage and inflammation were elevated: LDH, 464 U/L, and IL-2R, 3,376 U/mL. Troponin I was in the normal range, but brain natriuretic peptide was elevated at 138 pg/mL. A 12-lead electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm with a heart rate of 63 beats per minute, but right atrial overload was observed. Echocardiography showed normal left ventricular systolic function and a mass lesion occupying the RA and slight pericardial fluid (Fig. 3a). Contrast CT showed the RA mass extending to the SVC and inferior vena cava (IVC), and there was no other lymphadenopathy (Fig. 3b, c). After admission, a transvenous biopsy of the cardiac mass was performed, which revealed a high density of large round cells with irregular nuclei. DLBCL was diagnosed by immunohistochemical staining (germinal center B-cell subtype, CD20-positive, MUM1-positive, BCL6-positive, CD10-positive, CD3-negative, EBER-negative). Holter electrocardiograms performed during hospitalization showed ectopic atrial rhythm and junctional escape beats, sinus arrest up to 5.8 s, and AFL (Fig. 4). A temporary transvenous pacing lead was placed at the right ventricular apex because of repeated syncope, and subsequently, a ventricular-inhibited (VVI) pacemaker was implanted from the left precordium. Although the tumor had occupied most of the RA, there was no deterioration of respiratory state during or after PMI. After the pathological results were obtained, we consulted with a hematologist and considered chemotherapy, but the patient chose palliative care. The patient was then transferred to a hospice care facility and died one and a half months after diagnosis of DLBCL.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Case 2. (a) Echocardiogram performed on admission shows mass lesions occupying the right atrium (white arrows) and slight pericardial fluid (white asterisk). (b, c) Contrast computed tomography shows the right atrial mass extending to the supra vena cava and inferior vena cava (red arrows). (b) Axial image. (c) Coronal image. TV: tricuspid valve. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Case 2. Holter electrocardiogram using the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) lead position performed during hospitalization shows sinus rhythm with the finding of right atrial overload (a), ectopic atrial rhythm and junctional escape beats (b), sinus arrest up to 5.8 s (c), and atrial flutter (d). The electrocardiogram was recorded at a calibration of 10 mm/mV and a speed of 25 mm/s. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In this report, we present two cases of cardiac lymphoma that presented with SSS and AFL. By definition, these cases are both PCL because they presented with cardiac symptoms and significant tumor bulk was located in the heart.

In our two cases, tumors were found in the high RA between the right atrial appendage and the SVC junction, which was near the sinoatrial node, so we determined that SSS was secondary to lymphoma invasion. In an autopsy report of a similar case of right atrial cardiac lymphoma presenting with SSS, lymphoma infiltration and destruction of the sinus node structure were pathologically confirmed [3]. Our cases also had AFL in addition to SSS. Case 1 was diagnosed with typical AFL originating from the RA and traversing the cavotricuspid isthmus, based on the polarity of the sawtooth appearance of the flutter waves. Although there are few reports regarding cardiac lymphoma and AFL, we considered AFL to be also secondary to lymphoma because the RA was diffusely invaded, which predisposes to AFL. SSS is generally caused by age-related degenerative fibrosis of the sinus node, but in rare cases, it can be caused by infiltrative disease, including cardiac lymphoma. Cardiac lymphoma can cause disorders of the conduction system (SSS and/or atrioventricular conduction block) depending on the tumor location. In patients with bradyarrhythmia who also have B symptoms (fever, weight loss, and night sweats) and abnormal blood tests (elevated LDH and IL-2R), the possibility of cardiac lymphoma as an infiltrative disease should be considered.

In case 2, frequent Adams-Stokes attacks necessitated pacemaker implantation when the tumor occupied the RA. PMI before cardiac tumor regression was challenging because lead manipulation near the tumor can cause pulmonary tumor embolism. To minimize the risk of embolism, we did not position the atrial lead, although atrial pacing is functionally reasonable for SSS. Fortunately, there was no deterioration in respiratory status during or after PMI in case 2. The SVC and/or IVC may be narrowed or obstructed in PCL due to right atrial mass extension. In cases of cardiac lymphoma presenting with SSS complicated by SVC obstruction, there have been reports of inserting a leadless pacemaker via the femoral vein [4] and inserting an epicardial pacemaker to obtain a biopsy specimen and avoid tumor embolism [5]. However, there is currently no definitive guidance on the management of pacemaker implantation in patients with conduction system disorders. In patients with PCL, preoperative planning must include thorough evaluation of the extent of the tumor and development of a strategy regarding pacing mode, device selection, and vascular access. As mentioned earlier, the treatment varied for each case, and strategies must be devised with the heart team before an operation.

Many patients with SSS secondary to cardiac lymphoma, including case 2, require temporary pacing and/or PMI in the acute phase [2-6]. However, the SSS signs in case 1 gradually deteriorated and eventually required intervention by PMI. Although SSS may improve with treatment of cardiac lymphoma, subclinical sinus node dysfunction may exist and/or worsen in some cases even after complete remission of lymphoma. The clinical course of sinus node dysfunction varies between each patient, depending on the disease activity of lymphoma (size, growth rate, and degree of invasion). Therefore, long-term cardiac monitoring is necessary even after complete remission of lymphoma. If SSS does not return to sinus rhythm in parallel with improvement of lymphoma, we must consider the possibility of myocardial damage caused by chemotherapy. Case 1 received a cumulative dose of pirarubicin of 250 mg/m2, equivalent to 125 mg/m2 of doxorubicin, which is much lower than the dose reported to cause cardiotoxicity [7]. Because left ventricular systolic function was also preserved until the end of follow-up, anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy was not considered. CDE-11, which was administered before the recurrence of junctional escape beats, is also well tolerated as salvage chemotherapy for DLBCL, and there are no reports of cardiotoxicity in older adult patients [8]. This finding suggests that sinus node dysfunction secondary to CDE-11 is low.

In conclusion, PCL can lead to sinus node dysfunction and/or AFL secondary to tumor invasion into the sinoatrial node and whole RA. Since the clinical course of SSS may vary for each patient, long-term cardiac monitoring is necessary even after complete remission of lymphoma.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Author Contributions

TK, NM, AI, TF, KT, TA, KF, YN, YT, SM, and MO contributed to the study design, drafting, editing, and final approval of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available in this article.

Abbreviations

AFL: atrial flutter; CDE-11: carboplatin, dexamethasone, etoposide, and irinotecan; CT: computed tomography; DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FDG: fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose; 18F-FDG PET: 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography; GCD: gemcitabine, carboplatin, and dexamethasone; IL-2R: interleukin-2 receptor; IVC: inferior vena cava; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; PCL: primary cardiac lymphoma; PMI: permanent pacemaker implantation; RA: right atrium; R-THP-COP: rituximab, pirarubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone; SSS: sick sinus syndrome; SVC: superior vena cava; TV: tricuspid valve

| References | ▴Top |

- Petrich A, Cho SI, Billett H. Primary cardiac lymphoma: an analysis of presentation, treatment, and outcome patterns. Cancer. 2011;117(3):581-589.

doi pubmed - McAllister HA, Fenoglio JJ. Tumors of the cardiovascular system. In: Atlas of tumor pathology. 2nd Series. Fascicle 15. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1978. p. 99-100.

- Mohri T, Igawa O, Isogaya K, Hoshida K, Togashi I, Soejima K. Primary cardiac B-cell lymphoma involving sinus node, presenting as sick sinus syndrome. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2020;6(10):694-696.

doi pubmed - Kondo S, Osanai H, Sakamoto Y, Uno H, Tagahara K, Hosono H, Miyamoto S, et al. Secondary cardiac lymphoma presenting as sick sinus syndrome and atrial fibrillation which required leadless pacemaker implantation. Intern Med. 2021;60(3):431-434.

doi pubmed - Ito K, Nishimura Y, Tanaka H, Tejima T. Epicardial pacemaker implantation for sick sinus syndrome in a patient with supra vena cava obstructed by a primary cardiac lymphoma. J Cardiol Cases. 2020;21(6):234-237.

doi pubmed - Araki T, Namura M. Right atrial tumor and sick sinus syndrome. Intern Med. 2003;42(5):450-451.

doi pubmed - Hara T, Yoshikawa T, Goto H, Sawada M, Yamada T, Fukuno K, Kasahara S, et al. R-THP-COP versus R-CHOP in patients younger than 70 years with untreated diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A randomized, open-label, noninferiority phase 3 trial. Hematol Oncol. 2018;36(4):638-644.

doi pubmed - Yamasaki S, Tanimoto K, Kohno K, Kadowaki M, Takase K, Kondo S, Kubota A, et al. UGT1A1 *6 polymorphism predicts outcome in elderly patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with carboplatin, dexamethasone, etoposide and irinotecan. Ann Hematol. 2015;94(1):65-69.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cardiology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.