| Cardiology Research, ISSN 1923-2829 print, 1923-2837 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cardiol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 16, Number 5, October 2025, pages 433-446

Glycolysis-Related Genes, S100A8 and CXCL1, Participate in Acute Myocardial Infarction by Regulating Immune Cell Infiltration

Yu Zhanga, c, Hui Min Jiaa, c, Fu Xiang Ana, c, Xin Ru Wanga, Mei Zhu Yanb, Fu Li Liua, Bao Bao Fenga, Hong Jun Biana, d

aDepartment of Emergency Medicine, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, Shandong 250021, China

bDepartment of Emergency Medicine, Jinqiu Hospital of Liaoning Province, Shenyang, Liaoning 110016, China

cThese authors contributed equally to this work.

dCorresponding Author: Hongjun Bian, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, Shandong 250021, China

Manuscript submitted May 19, 2025, accepted August 27, 2025, published online October 10, 2025

Short title: Role of Glycolysis During AMI

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cr2090

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is one of the most severe forms of acute coronary syndrome. During myocardial ischemia, cardiac glycogen is metabolized through glycolysis, which becomes the primary source of ATP. The genetic regulation of glycolysis is well established, yet its contribution to AMI pathogenesis remains poorly understood. This study aimed to use bioinformatics approaches to identify glycolysis-related genes (GRGs) associated with AMI, providing a foundation for their potential applications as molecular markers and therapeutic targets.

Methods: GRGs were retrieved from the GeneCards database. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was applied to the GSE66360 dataset to identify hub genes, which were validated by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Immune cell infiltration and its association with hub gene expression in AMI were further examined using the CIBERSORT algorithm.

Results: Analysis of the GSE66360 dataset identified 695 differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) indicated that these genes may contribute to AMI pathogenesis by regulating cellular energy metabolism. Intersecting DEGs with GRGs yielded 31 differentially expressed glycolysis-related genes (DEGRGs). Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses suggested that DEGRGs may influence AMI development by modulating immune cell function and immune response status. Construction of a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network identified seven hub genes, all of which demonstrated diagnostic performance in GSE66360 based on the ROC analysis. Validation in the independent dataset GSE59867 confirmed two hub genes with diagnostic potential. Immune infiltration analysis further revealed that these two hub genes were significantly associated with multiple types of immune cells.

Conclusion: Two GRGs, S100A8 and CXCL1, were identified as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in AMI. Both genes were associated with immune cell infiltration, suggesting that they may contribute to AMI pathogenesis through immunometabolic regulation. Importantly, combined detection of these hub genes may facilitate early risk stratification and prediction of major adverse cardiac events, offering a new direction for AMI diagnosis and prognosis.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction; Energy metabolism; Glycolysis; Immune infiltration; Bioinformatics

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for approximately 45% of all deaths in Europe [1], including 49% of all deaths in women and 40% in men [2]. Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is defined as cardiomyocyte necrosis in the clinical context of acute myocardial ischemia, resulting from atherothrombotic events or other causes of myocardial ischemia and myocyte injury [3]. AMI represents one of the most critical forms of acute coronary syndrome. The acute phase of AMI is often complicated by malignant arrhythmia and sudden death, while the chronic phase is frequently accompanied by impaired cardiac function. Among the various biomarkers evaluated for AMI diagnosis, such as high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn), creatine kinase-MB, myosin-binding protein C, and copeptin, only hs-cTn is currently recommended in all patients with suspected AMI [3]. Although additional biomarkers may provide incremental value when combined with hs-cTn, their standalone diagnostic utility remains limited. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying AMI and identifying novel contributors to its pathogenesis may support the discovery of new biomarkers for diagnosis and treatments.

Healthy myocardium is highly metabolically adaptable, capable of utilizing diverse substrates to sustain energy production under physiological conditions. Under normoxic conditions, mitochondrial oxidative metabolism generates approximately 90% of cardiac ATP, whereas cytosolic glycolysis contributes only 5-10%. During ischemia, however, cardiac metabolism shifts rapidly, with suppression of oxidative metabolism compensated by activation of anaerobic glycolysis to conserve oxygen. Consequently, glycogen-derived glycolysis becomes the predominant source of ATP [4, 5].

Lactate, the end-product of glycolysis, is a key metabolic intermediate, and its circulating levels carry established prognostic significance in AMI [6]. Enhanced glycolysis can protect the ischemic myocardium by reducing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and limiting cell death during ischemia-reperfusion injury [7-9]. However, excessive glycolysis may be detrimental; it contributes to sepsis-related macrophage activation [10], and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1)-dependent glycolysis has been shown to exacerbate lung fibrogenesis during Streptococcus pneumoniae infection [11, 12]. Growing evidence further indicates that metabolic reprogramming is critical for immune regulation, particularly under ischemic conditions, where hypoxia suppresses mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and promotes reliance on glycolysis. For instance, FASLG, a key mediator of necroptosis, may influence AMI by modulating immune cell infiltration [13]. Moreover, the activation of the proinflammatory transcriptional program is closely tied to preferential glucose metabolism in leukocytes. A deeper understanding of glycolysis-driven metabolic adaptation could reveal novel therapeutic targets to reduce ischemic injury and inflammation, thereby preventing progression to heart failure [14]. Nevertheless, the contribution of glycolysis-related genes (GRGs) to AMI pathogenesis remains poorly defined, and further studies are required to clarify their roles in myocardial apoptosis, necrosis, necroptosis, and immune modulation.

In this study, weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was applied to the GSE66360 dataset to identify key gene modules associated with AMI, followed by comprehensive bioinformatic analyses. Among the candidate genes, S100A8 and CXCL1 were found to be upregulated following AMI and were identified as potential biomarkers. Their differential expression was further validated, and downstream analyses were performed to investigate potential mechanisms linking these genes to AMI pathogenesis.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Dataset acquisition and preprocessing

The GSE66360 (GPL570) dataset was obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO [15]) database and used as the training set, while GSE59867 (GPL6244) was used as the validation set. The GSE66360 dataset includes blood samples from 49 patients with AMI and 50 healthy controls, whereas GSE59867 comprises blood samples from 111 AMI patients and 46 patients with stable coronary artery disease without a history of myocardial infarction. Probe identifiers were converted to gene symbols using R software (version 4.2.1), with the first probe value retained when multiple probes mapped to the same gene symbol. In addition, a total of 4110 GRGs were retrieved from the Human Gene Database (GeneCards [16]).

WGCNA

WGCNA was performed to identify gene modules with similar expression patterns, examine interconnections between modules, and relate modules to candidate biomarkers or therapeutic targets. WGCNA was applied to all samples in the GSE66360 dataset using the “WGCNA” package in R software (version 4.2.1). The “pickSoftThreshold” function was used to construct a weighted network by assessing pairwise gene expression similarities, and a soft threshold of 12 was selected based on the scale-free topology fitting index and connectivity. The correlation matrix was then converted into an adjacency matrix, from which a topological overlap matrix (TOM) was generated. Hierarchical clustering was performed on the TOM to identify co-expression modules. A minimum module size of 30 was set, and modules with highly similar expression patterns were merged at a threshold of 0.9. Finally, module-trait correlations were calculated, and the module with the highest correlation to AMI was selected for subsequent analysis.

Identification of hub genes

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the AMI and healthy control groups in the GSE66360 dataset using the “stats” package in R, and results were visualized with “ggplot2”. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the “limma” package with thresholds of |log2 fold change (FC)| > 1 and P < 0.05 [17, 18]. DEGs were visualized in a volcano plot generated with “ggplot2” and subsequently intersected with GRGs to obtain differentially expressed glycolysis-related genes (DEGRGs), which were displayed using online Venn diagram tools and the VennDetail Shiny App [19].

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

GSEA was conducted to identify pathways enriched in AMI compared with healthy controls. This approach allowed the detection of gene sets with potential biological relevance, even when the individual gene expression changes were modest. A significance threshold of P < 0.05 was applied.

Analysis of DEG identification and functional enrichment

Functional enrichment analysis of DEGs was performed using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases. GO enrichment was conducted across the categories of biological pathway (BP), molecular function (MF), and cellular components (CC), while KEGG analysis was applied to identify gene-related signaling pathways. Both GO and KEGG analyses were conducted with the “clusterProfiler” package in R, and the results were visualized with the “enrichplot” R package.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network construction

To identify the core DEGs and key gene modules, a PPI network was constructed using the STRING database [20] with a confidence score threshold of > 0.4 and visualized in Cytoscape (version 3.10.1). The CytoHubba algorithm in Cytoscape software was used to calculate maximal clique centrality (MCC) values, and the top 10% of genes ranked by MCC were retained. Genes were additionally required to be involved in at least three AMI-related pathways. Lastly, based on the degree and MCC algorithm in Cytoscape, seven hub genes were identified [21].

Expression and diagnostic performance of hub genes

The “stats” package in R was used to conduct the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to evaluate expression differences of the seven hub genes between AMI and healthy controls, and results were visualized with “ggplot2”. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to assess the diagnostic performance of hub genes in both the GSE66360 and GSE59867 datasets. Diagnostic performance was further validated in the GSE59867 dataset.

Immune cell infiltration analysis

Immune cell composition was estimated using the CIBERSORT algorithm, which applies a deconvolution approach to quantify the relative proportions of 22 immune cell types. To further investigate immune mechanisms in AMI, correlations between hub gene expression and immune cell abundance were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation analysis in R. Results were visualized with “ggplot2”.

| Results | ▴Top |

Identification of AMI-associated genes by WGCNA

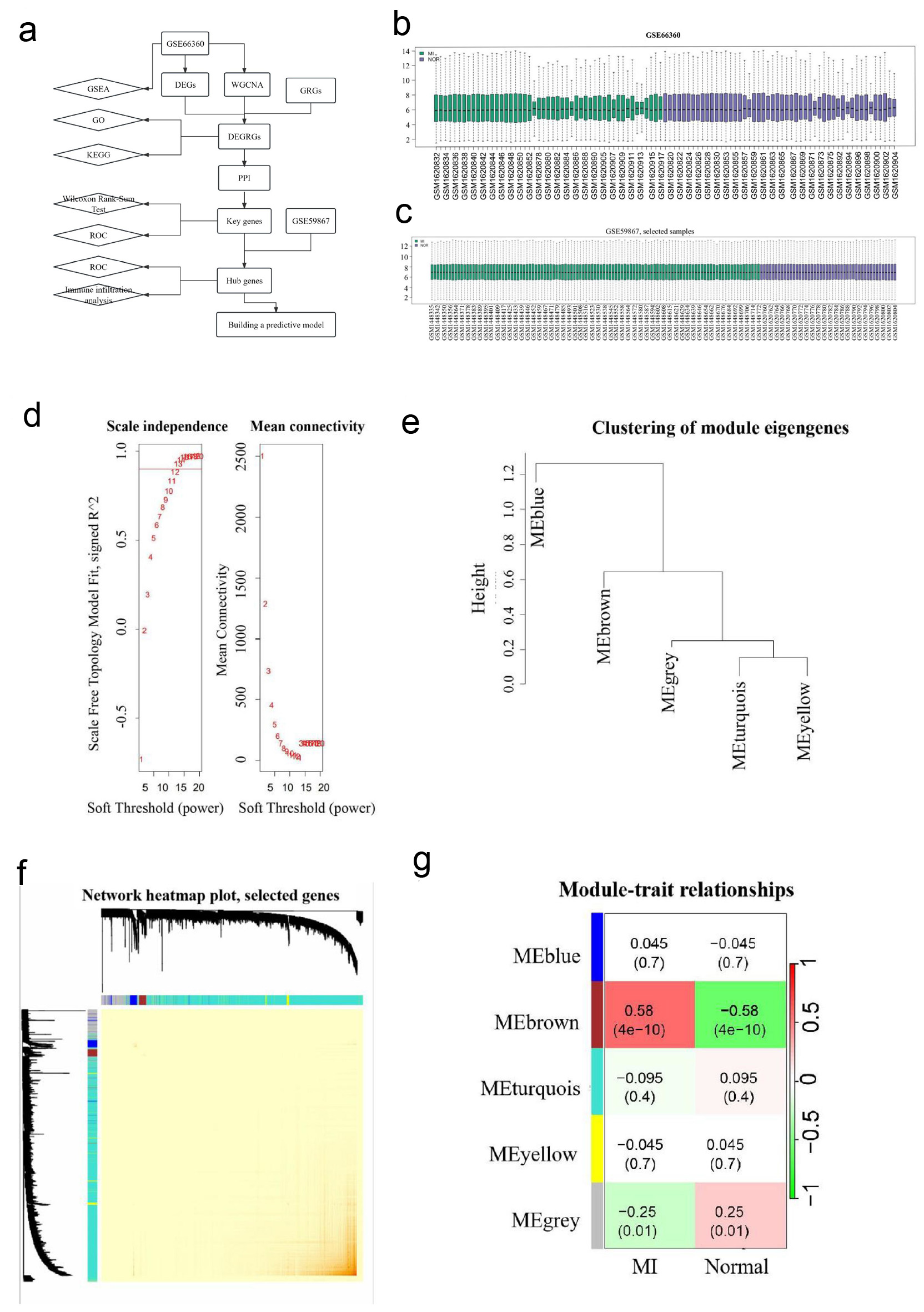

A multi-step analysis of the GSE66360 and GSE59867 datasets was performed to identify and validate candidate hub genes (Fig. 1a). Data quality was assessed using boxplots, which showed consistent distributions of median, upper quartile, and lower quartile across both datasets (Fig. 1b, c).

Click for large image | Figure 1. WGCNA analysis. (a) A flow diagram of using a multi-step strategy to select hub genes of AMI in GSE66360 dataset and DEGRGs, and carry out multi-step validation. (b) Data quality evaluation of GSE66360 datasets. (c) Data quality evaluation of GSE59867 dataset. (d) Analysis scale free topology fitting index and connectivity, 12 is the optimal soft threshold. (e) Clustering diagram of module feature genes. (f) Clustering dendrogram of genes, with dissimilarity based on the topological overlap. The saddlebrown module was considered to be the most relevant to AMI. (g) A heatmap of the correlation between different color modules and clinical traits. WGCNA revealed that genes contained in the saddlebrown module were maximally associated with AMI. WGCNA: weighted gene co-expression network analysis; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; DEGRGs: differentially expressed glycolysis related genes; GRG: glycolysis-related gene; PPI: protein-protein interaction; GSEA: gene set enrichment analysis; GO: Gene Ontology; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; ROC: receiver operating characteristic. |

WGCNA was performed on 99 samples in the GSE66360 dataset to identify gene modules associated with AMI. A soft threshold power of 12 was selected to achieve scale-free topology (Fig. 1d). Modules with similar expression patterns were merged at a threshold of 0.9 (Fig. 1e), resulting in five distinct modules (Fig. 1f). Based on module-trait correlations, the brown module, comprising 184 genes, showed the highest AMI correlation index (P = 4.38 × 10-10) (Fig. 1g).

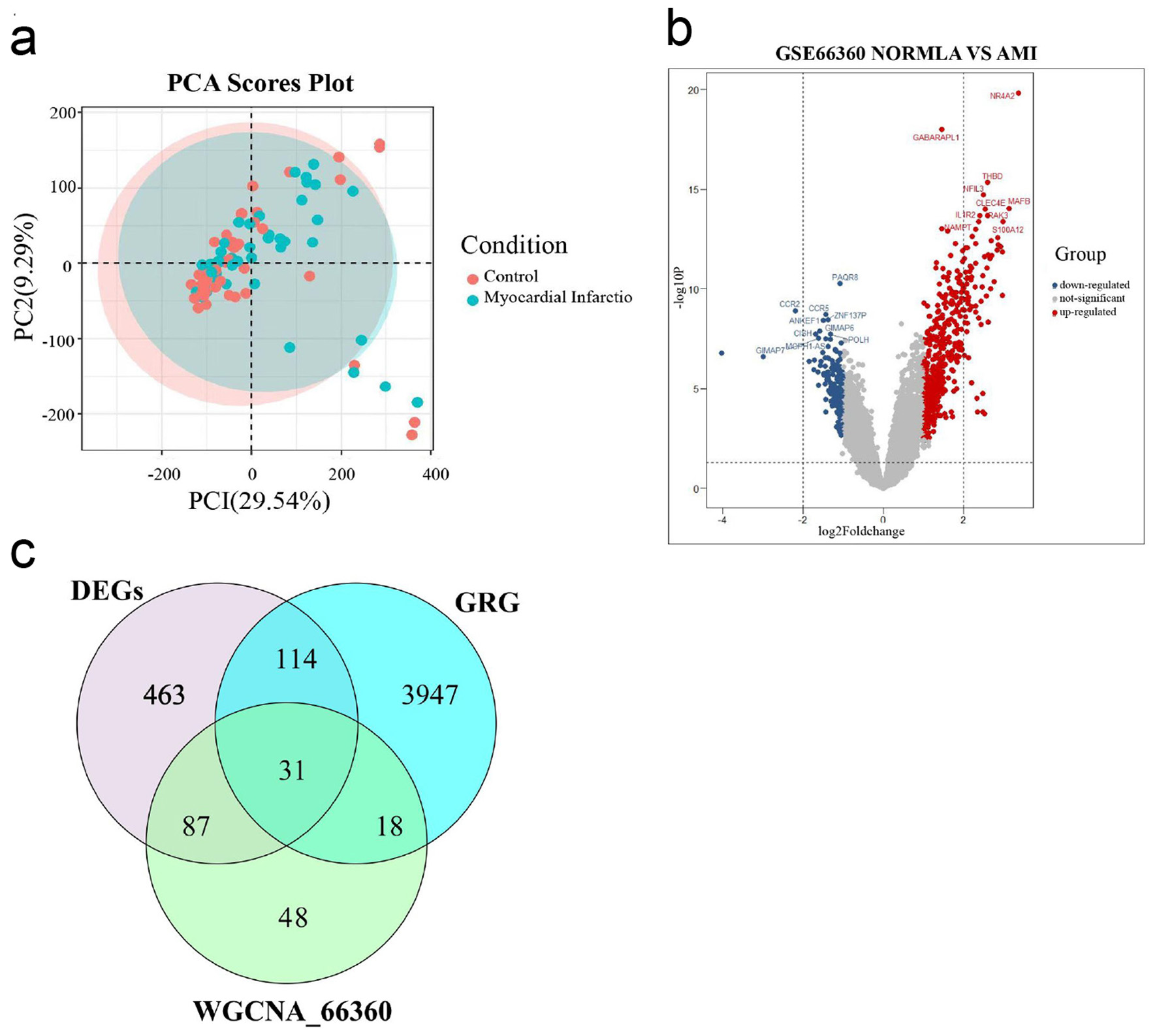

Thirty-one DEGRGs obtained

PCA demonstrated clear separation between AMI and healthy control groups in the GSE66360 dataset (Fig. 2a). A total of 695 DEGs were identified, including 493 upregulated genes and 202 down-regulated genes (Fig. 2b). Intersection of DEGs with GRGs yielded 31 DEGRGs (Fig. 2c).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Select DEGRGs. (a) PCA of AMI group and healthy control group. (b) A volcano plot of difference analysis between AMI group and healthy control group in GSE66360. (c) Venn diagram of intersecting genes in DEGs, WGCNA_GSE66360, GRG. DEGRGs: differentially expressed glycolysis related genes; PCA: principal component analysis; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; DEGs: differentially expressed genes; GRG: glycolysis-related gene; WGCNA: weighted gene co-expression network analysis. |

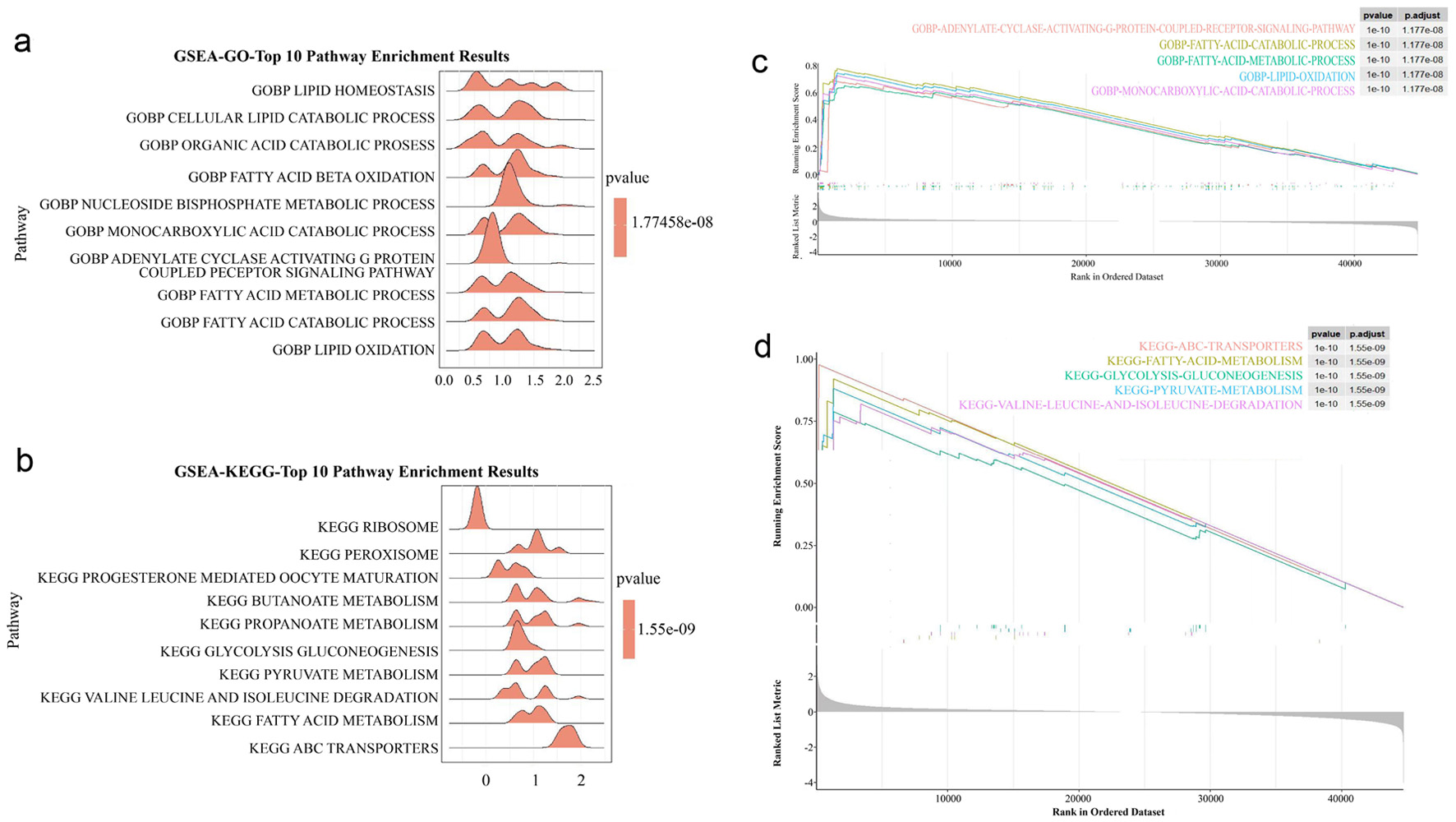

GSEA

GSEA was applied to the GSE66360 dataset to evaluate functional differences between AMI and healthy controls. The top 10 enriched pathways were identified through GO (Fig. 3a) and KEGG (Fig. 3b) analyses. GO enrichment indicated that 695 DEGs were primarily involved in processes such as adenylate cyclase-activating G protein-coupled receptor signaling, fatty acid catabolism, fatty acid metabolism, lipid oxidation, and monocarboxylic acid catabolism (Fig. 3c). KEGG pathway analysis further revealed enrichment in pathways including ABC transporters, fatty acid metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, pyruvate metabolism, and branched-chain amino acid degradation (Fig. 3d). Together, GO and KEGG results suggest that DEGs may contribute to AMI pathogenesis by modulating immune cell function and immune response status.

Click for large image | Figure 3. GSEA analysis. (a) GO analysis of GSEA enrichment analysis. (b) KEGG analysis of GSEA enrichment analysis. (c) The main enriched pathway of GO. (d) The main enriched pathway of KEGG. GSEA: gene set enrichment analysis; GO: Gene Ontology; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; DEGs: differentially expressed genes; GRG: glycolysis-related gene. |

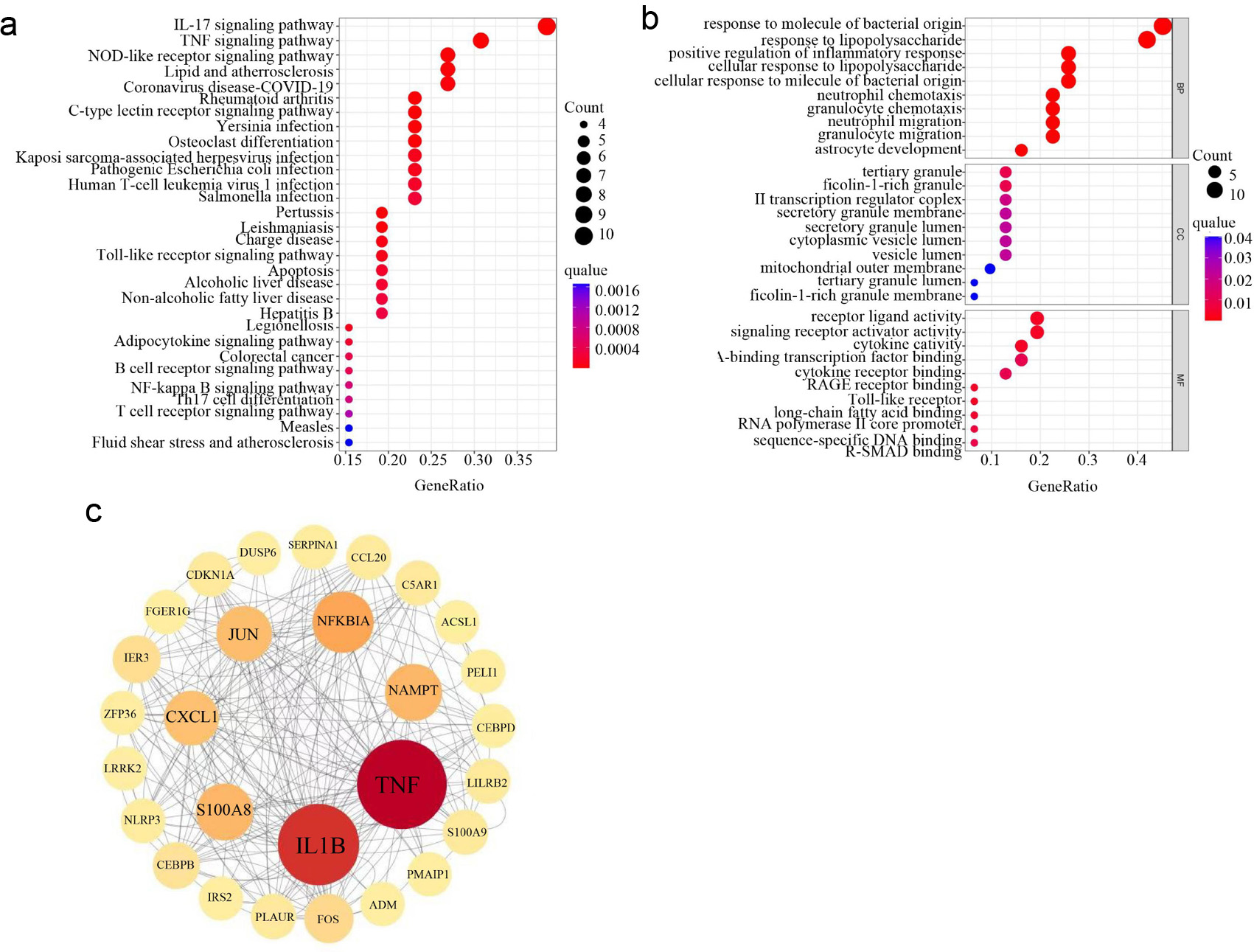

Detection and enrichment analysis of DEGRGs in high and low expression groups of AMI patients

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed to investigate the functions of DEGRGs. GO enrichment in the BP category indicated that DEGRGs were primarily involved in responses to molecules of bacterial origin, particularly lipopolysaccharide, as well as regulation of inflammatory processes, neutrophil and granulocyte chemotaxis, and neutrophil migration (Fig. 4a). KEGG analysis revealed enrichment in immune- and inflammation-related pathways, including interleukin (IL)-17, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor, C-type lectin receptor, Toll-like receptor (TLR), and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling. Additional enriched pathways included adaptive immunity (B-cell receptor signaling, T-cell receptor signaling, Th17 cell differentiation), apoptosis, adipocytokine signaling, and the lipid and atherosclerosis pathway (Fig. 4b). Together, GO and KEGG analyses indicated a role for DEGRGs in modulating immune function and inflammatory responses, which contribute to AMI pathogenesis.

Click for large image | Figure 4. Construction of PPI networks and identification of hub genes based on DEGRGs. (a) GO enrichment analysis of DEGRGs. (b) KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGRGs. (c) Screening hub genes by constructing PPI network and get seven hub genes (TNF, IL1B, NFKBIA, NAMPT, S100A8, CXCL1, and JUN). The circle with the larger diameter and deeper color indicates the higher intervention centrality and central position in the network. PPI: protein-protein interaction; DEGRGs: differentially expressed glycolysis related genes; GO: Gene Ontology; KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. |

Construction of PPI networks and identification of hub genes based on DEGRGs

To investigate interactions among DEGRGs, a PPI network was constructed using the STRING database. The network comprised 28 nodes and 220 edges. Based on the degree algorithm in Cytoscape, seven hub genes were identified: TNF, IL1B, NFKBIA, NAMPT, S100A8, CXCL1, and JUN (Fig. 4c).

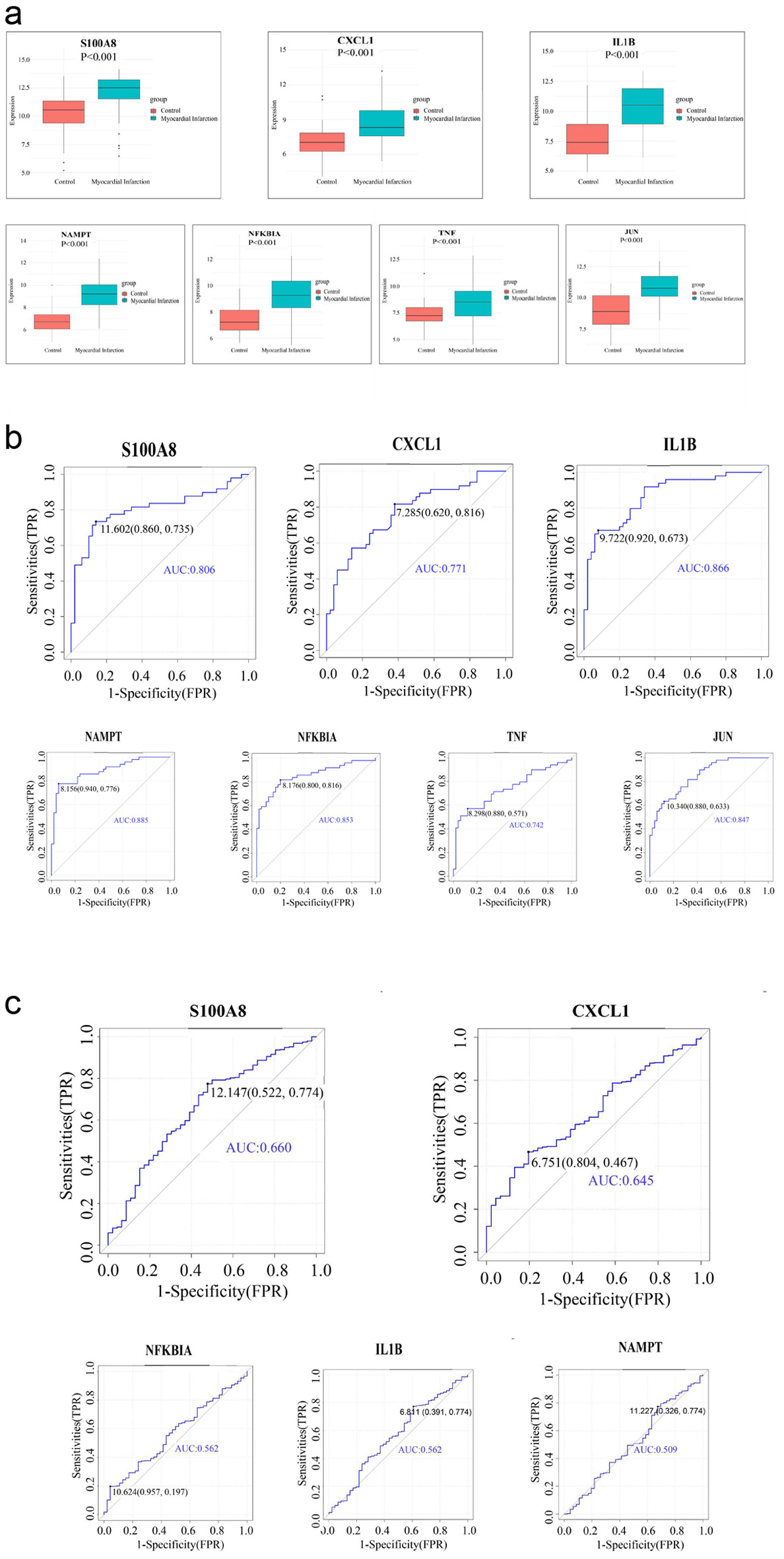

Two hub genes have good diagnostic efficacy in AMI

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was conducted to assess expression differences of hub genes in the GSE66360 and GSE59867 datasets. All seven hub genes showed significant differential expression between AMI and controls in both datasets (Fig. 5a). ROC curve analysis demonstrated that all seven hub genes had an area under the curve (AUC) > 0.6 in GSE66360, indicating good diagnostic performance (Fig. 5b). Validation in the GSE59867 dataset confirmed five of these genes, among which two (S100A8, CXCL1) achieved AUC values between 0.6 and 0.8 (Fig. 5c). While these results suggest diagnostic potential, further validation is required due to the absence of detailed clinical characteristics in the datasets and the complexity of AMI pathogenesis, which involves multiple gene interactions.

Click for large image | Figure 5. Assess the diagnostic efficacy of seven hub genes and get two hub genes (S100A8, CXCL1) with good diagnostic performance in AMI. (a) Expression of hub genes in GSE66360 dataset. (b) ROC curve of hub genes in GSE66360 dataset. (c) ROC curve of hub genes in GSE59867 dataset. AMI: acute myocardial infarction; ROC: receiver operating characteristic. |

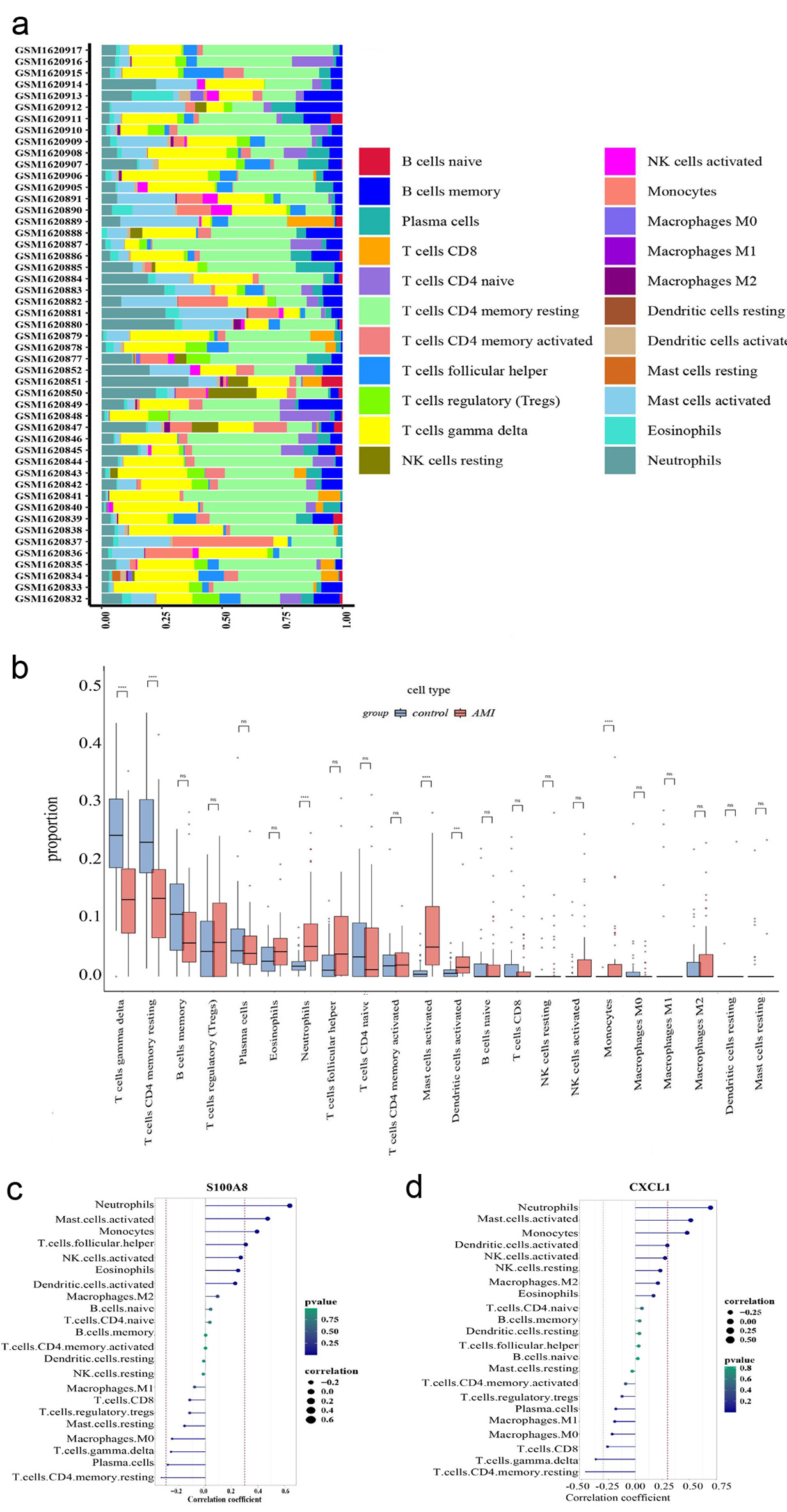

Correlation analysis of hub genes with immune cell infiltration in patients with AMI

The CIBERSORT algorithm was used to estimate immune cell composition in AMI specimens, showing significant differences compared with controls (Fig. 6a). Specifically, levels of γδ T cells, resting CD4 memory T cells, neutrophils, activated mast cells, activated dendritic cells, and monocytes were dysregulated in AMI (Fig. 6b). Spearman’s rank correlation analysis further demonstrated that CXCL1 expression was positively correlated with neutrophils, activated mast cells, and monocytes, but negatively correlated with resting CD4 memory T cells and γδ T cells (Fig. 6c). Similarly, S100A8 displayed a similar pattern, with positive correlations to neutrophils, activated mast cells, and monocytes, and a negative correlation to resting CD4 memory T cells (Fig. 6d). These findings suggest that CXCL1 and S100A8 may be associated with immune cell dysregulation in AMI.

Click for large image | Figure 6. Immune cell infiltration analysis. (a) The box plot shows the relative percentages of different types of immune cells in all AMI samples. The vertical axis shows the 49 AMI samples, and the length of each color block on the horizontal axis indicates its percentage (0 - 1) of all immune cells. (b) Comparison of the proportion of various immune cell infiltrates between AMI and healthy control. (c) Correlation between CXCL1 and infiltrating immune cells. (d) Correlation between S100A8 and infiltrating immune cells. AMI: acute myocardial infarction. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

AMI is a leading cause of cardiovascular mortality worldwide. Timely intervention can significantly reduce complications and improve prognosis [22]. The heart is one of the most energy-demanding organs, with mitochondrial oxidative metabolism generating more than 80% of ATP required for normal myocardial function. Consequently, cardiomyocytes are highly sensitive to hypoxia and oxidative stress induced by ischemia-reperfusion and myocardial infarction (MI) [23]. Studies have shown that hypoxia for 6 h followed by 18 h of reoxygenation, or sustained hypoxia for more than 24 h, reduces cardiomyocyte viability by 59% and 51%, respectively [24]. Hypoxia impairs mitochondrial function, disrupts energy metabolism, induces oxidative stress, and ultimately causes severe mitochondrial and organ damage [25]. Beyond the primary glycolytic pathway, auxiliary glucose metabolism pathways, including the polyol, hexosamine, and pentose phosphate pathways, also contribute to cardiovascular pathophysiology during ischemia-reperfusion. Thus, targeting glycolysis and related metabolic processes represents a promising strategy for therapeutic intervention in CVD [26]. Alterations in cardiac energy metabolism after MI contribute to the development and severity of heart failure (HF) [27]. Modulating cardiac energy metabolism is therefore considered a potential therapeutic approach to mitigate HF progression and improve clinical outcomes [28]. A deeper understanding of the mechanisms regulating cardiac energy metabolism may facilitate the discovery of novel metabolic targets and strategies for prognostic assessment and AMI treatment.

Current pharmacological strategies to improve cardiac energy metabolism and energy supply primarily focus on three areas: regulating substrate utilization, enhancing mitochondrial function, and supporting ATP synthesis and transport. By modulating these processes, such therapies aim to preserve myocardial energy balance, improve cardiac performance, and delay the progression of CVD [29-31]. Agents that regulate substrate utilization include trimetazidine and levocarnitine, which shift substrate preference away from fatty acids towards glucose, thereby improving metabolic efficacy during ischemia. Metformin and dapagliflozin regulate sugar metabolism and have demonstrated cardioprotective effects. Compounds including coenzyme Q10 and the reduced form of nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide (NADH) support mitochondrial function and reduce oxidative stress, while phosphocreatine has been studied as an adjunct to maintain ATP availability during ischemia.

In this study, GSEA showed that DEGs were predominantly enriched in pathways related to energy metabolism, inflammation, and immune regulation. Functional enrichment of the 31 identified DEGRGs further confirmed their involvement in immune-related pathways, consistent with the broader DEG analysis. Construction of a PPI network combined with gene expression and diagnostic analyses identified S100A8 and CXCL1 as two key hub genes associated with AMI. Immune cell deconvolution with CIBERSORT demonstrated significant differences in inflammatory cell populations between AMI and controls, and both hub genes were strongly correlated with these immune alterations. These findings suggest that S100A8 and CXCL1 may contribute to AMI pathogenesis through their roles in immune cell regulation, consistent with the enrichment results and Spearman’s rank correlation analysis.

S100A8 and S100A9, members of the calcium-binding S100 protein family, have been recognized as proinflammatory danger signals once released into the extracellular space [32]. They have been implicated in MI through receptor-mediated mechanisms, including interactions with the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). Functionally, S100A8/A9 can induce calcium ion (Ca2+) release in cardiomyocytes and drive macrophage polarization toward a proinflammatory M1 phenotype [33], thereby impairing perfusion of ischemic tissue. Elevated serum concentrations of S100A8/A9 have been reported in acute coronary syndrome (ACS), coronary artery calcification, and cardiovascular intimal hyperplasia [25]. S100A8/A9 exert dual effects during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. On the one hand, they activate proinflammatory signaling through TLR4, leading to extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway activation, NADH activity inhibition, and mitochondrial respiration impairment. This disruption of energy metabolism amplifies oxidative stress, ultimately causing cardiomyocyte death and exacerbated myocardial injury [34]. On the other hand, experimental studies suggest that S100A8/A9 can support immunoregulation and tissue repair by modulating gene expression, contributing to improved contractility and reduced fibrosis after ischemia-reperfusion [35]. Consistently, S100A8/A9 are elevated in infarcted myocardium and plasma of AMI patients [36], and their sustained upregulation has been implicated in post-MI HF [37]. Beyond CVD, S100A9 has been shown to enhance glycolytic activity in tumor cells via a c-Myc-dependent pathway, thereby influencing immune cell infiltration and long-term patient outcomes [38]. S100A8/A9 have also been proposed as diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers in cancer [39] and acute lymphocytic myocarditis [40]. Importantly, pharmacological blockade of S100A8/A9 with ABR-238901 exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects and mitigates myocardial dysfunction [41]. Taken together, these findings suggest that S100A8/A9 are closely related to myocardial energy metabolism and inflammation after MI, underscoring their potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets in AMI.

Chemokines are a family of small cytokines with potent chemotactic properties, guiding the directed migration of leukocytes and other cell types to sites of inflammation or injury. They are critical for immune surveillance and host defense, but also contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory, autoimmune, and neoplastic diseases [42]. Chemokines act as key mediators of intercellular communication, expressed by both immune and non-immune cells, and participate in diverse physiological and pathological processes. A central role is the recruitment of neutrophils, the first line of host defense against bacterial infection. CXCL1, primarily expressed in neutrophils, macrophages, and epithelial cells, functions as a pro-inflammatory mediator that promotes neutrophil and monocyte infiltration [43]. The CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling axis has been shown to mediate Ang II-induced cardiac hypertrophy, inflammation, and remodeling [44], whereas its antagonism reduces myocardial fibrosis and thereby preserves cardiac function [43, 45]. Elevated plasma levels of CXCL1 have also been reported in AMI patients compared with healthy controls [46]. Beyond its chemotactic role, CXCL1 also influences metabolic pathways; it regulates glycolysis and lactate production, thereby facilitating neutrophil mobilization from the bone marrow [47]. These findings suggest that CXCL1 may contribute to AMI pathogenesis not only by promoting immune cell infiltration but also by altering energy metabolism in cardiomyocytes and immune cells. CXCL1 expression can be triggered by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [48] or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [49, 50], linking it to both infectious and sterile inflammatory responses. Outside CVDs, CXCL1 has been implicated in rheumatoid arthritis, melanoma, and gastric cancer, where it enhances COX-2 expression in synovial fibroblasts [51], stimulates tumor proliferation (initially referred to as melanoma growth-stimulatory activity, MGSA), and is upregulated by Helicobacter pylori in gastric epithelial cells [52]. In summary, these findings highlight CXCL1 as a multifunctional chemokine with both pathogenic and metabolic roles. Further studies are needed to determine whether CXCL1 acts as a primary driver of neutrophil chemotaxis in AMI or represents a secondary response to tissue injury.

Immune cells play important roles in the pathogenesis of CVDs, including AMI [53]. Their metabolic programming is closely linked to functional state: effector T cells, such as CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and CD4+ helper T cells, rely primarily on aerobic glycolysis, whereas memory T cells and regulatory T cells depend on fatty acid oxidation [54]. Following AMI, multiple immune cell subtypes, including neutrophils and monocyte/macrophages, are dynamically recruited to the injured myocardium, driving robust inflammatory responses [55]. Inflammation further shapes post-AMI pathology by influencing immune cells, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells, thereby contributing to vascular remodeling and lesion progression [56, 57]. Among these immune cell populations, neutrophils are the first responders to the infarcted myocardium, where they promote inflammation and initiate wound-healing cascades [14]. This activity is tightly coupled to metabolism, as neutrophil proinflammatory function depends heavily on glycolysis [58]. Resting neutrophils express GLUTs, including GLUT1, GLUT3, and GLUT4, whereas activation induces marked GLUT1 upregulation [59] accompanied by enhanced glucose uptake [60]. This metabolic shift fuels the release of matrix-degrading enzymes and contributes to post-infarction adverse remodeling [61]. Similarly, aerobic glycolysis has been identified as the primary energy source for activated dendritic cells [62], neutrophils [63], and M2 macrophages [64]. Consistent with these observations, our findings indicate that the two hub genes S100A8 and CXCL1 are correlated with multiple immune cell populations. These genes may influence AMI pathogenesis by modulating immune cell metabolism and function and could represent potential targets for more precise diagnosis and therapeutic strategies.

Despite these findings, a few limitations are acknowledged. First, our analyses were based on the whole-blood transcriptomic dataset, which lacks detailed clinical information such as age, sex, and comorbidities. These missing variables may introduce confounding factors in both gene expression and immune infiltration analyses. Secondly, PCA, while useful for dimensionality reduction, cannot capture nonlinear relationships and may overlook biologically relevant features with low variance, potentially limiting the accuracy of data interpretation. Finally, our conclusions were drawn from bioinformatic analyses, and experimental validation through in vitro and in vivo studies will be essential to investigate the mechanistic interplay between S100A8, CXCL1, and AMI pathogenesis.

In conclusion, this study identified two GRGs, S100A8 and CXCL1, as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in AMI through comprehensive bioinformatic analyses of publicly available datasets. Both genes were associated with immune cell infiltration, suggesting that they may contribute to AMI pathogenesis via immunometabolic regulation. Importantly, combined detection of these hub genes may enable earlier risk stratification of AMI patients and prediction of major adverse cardiac events, providing a new direction for diagnosis and prognosis. These findings lay the groundwork for the development of novel diagnostic strategies and therapeutic interventions, although further experimental validation will be required to confirm their clinical utility.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Professor Jianni Qi for her guidance on the design and writing of this study.

Financial Disclosure

This work was supported in part by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2022MH146).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

HB designed this article. YZ, HJ, and FA collected and assembled the data. YZ, HJ, FA, XW, MY, and HB analyzed and interpreted. YZ wrote the main manuscript text. FL, BF, and HB revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the first and corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Townsend N, Nichols M, Scarborough P, Rayner M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2015: epidemiological update. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(40):2673-2674.

pubmed - Townsend N, Wilson L, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M, Nichols M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(42):3232-3245.

doi pubmed - Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, Barbato E, Berry C, Chieffo A, Claeys MJ, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(38):3720-3826.

doi pubmed - Zuurbier CJ, Bertrand L, Beauloye CR, Andreadou I, Ruiz-Meana M, Jespersen NR, Kula-Alwar D, et al. Cardiac metabolism as a driver and therapeutic target of myocardial infarction. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(11):5937-5954.

doi pubmed - Kolwicz SC, Jr., Purohit S, Tian R. Cardiac metabolism and its interactions with contraction, growth, and survival of cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2013;113(5):603-616.

doi pubmed - Ouyang J, Wang H, Huang J. The role of lactate in cardiovascular diseases. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21(1):317.

doi pubmed - Gu X, Bao N, Zhang J, Huang G, Zhang X, Zhang Z, Du Y, et al. Muscone ameliorates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by promoting myocardial glycolysis. Heliyon. 2023;9(11):e22154.

doi pubmed - Beltran C, Pardo R, Bou-Teen D, Ruiz-Meana M, Villena JA, Ferreira-Gonzalez I, Barba I. Enhancing glycolysis protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury by reducing ROS production. Metabolites. 2020;10(4).

doi pubmed - Pan Q, Xie X, Yuan Q. Monocarboxylate transporter 4 protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by inducing oxidative phosphorylation/glycolysis interconversion and inhibiting oxidative stress. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2023;50(12):954-963.

doi pubmed - Xie M, Yu Y, Kang R, Zhu S, Yang L, Zeng L, Sun X, et al. PKM2-dependent glycolysis promotes NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13280.

doi pubmed - Cho SJ, Moon JS, Nikahira K, Yun HS, Harris R, Hong KS, Huang H, et al. GLUT1-dependent glycolysis regulates exacerbation of fibrosis via AIM2 inflammasome activation. Thorax. 2020;75(3):227-236.

doi pubmed - Lin HC, Chen YJ, Wei YH, Chuang YT, Hsieh SH, Hsieh JY, Hsieh YL, et al. Cbl Negatively Regulates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation through GLUT1-Dependent Glycolysis Inhibition. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(14).

doi pubmed - Jia HM, An FX, Zhang Y, Yan MZ, Zhou Y, Bian HJ. FASLG as a key member of necroptosis participats in acute myocardial infarction by regulating immune infiltration. Cardiol Res. 2024;15(4):262-274.

doi pubmed - Chen Z, Dudek J, Maack C, Hofmann U. Pharmacological inhibition of GLUT1 as a new immunotherapeutic approach after myocardial infarction. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;190:114597.

doi pubmed - https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/.

- https://www.genecards.org/.

- Dora F, Renner E, Keller D, Palkovits M, Dobolyi A. Transcriptome profiling of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex in suicide victims. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(13).

doi pubmed - Jia ZC, Li YQ, Zhou BW, Xia QC, Wang PX, Wang XX, Sun ZG, et al. Transcriptomic profiling of human granulosa cells between women with advanced maternal age with different ovarian reserve. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2023;40(10):2427-2437.

doi pubmed - http://hurlab.med.und.edu:3838/VennDetail/.

- https://string-db.org/.

- Xu M, Ouyang T, Lv K, Ma X. Integrated WGCNA and PPI network to screen Hub genes signatures for infantile hemangioma. Front Genet. 2020;11:614195.

doi pubmed - Bajaj A, Sethi A, Rathor P, Suppogu N, Sethi A. Acute complications of myocardial infarction in the current era: diagnosis and management. J Investig Med. 2015;63(7):844-855.

doi pubmed - Kuznetsov AV, Javadov S, Sickinger S, Frotschnig S, Grimm M. H9c2 and HL-1 cells demonstrate distinct features of energy metabolism, mitochondrial function and sensitivity to hypoxia-reoxygenation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1853(2):276-284.

doi pubmed - Kang PM, Haunstetter A, Aoki H, Usheva A, Izumo S. Morphological and molecular characterization of adult cardiomyocyte apoptosis during hypoxia and reoxygenation. Circ Res. 2000;87(2):118-125.

doi pubmed - Turer AT, Hill JA. Pathogenesis of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and rationale for therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(3):360-368.

doi pubmed - Chen S, Zou Y, Song C, Cao K, Cai K, Wu Y, Zhang Z, et al. The role of glycolytic metabolic pathways in cardiovascular disease and potential therapeutic approaches. Basic Res Cardiol. 2023;118(1):48.

doi pubmed - Karwi QG, Zhang L, Wagg CS, Wang W, Ghandi M, Thai D, Yan H, et al. Targeting the glucagon receptor improves cardiac function and enhances insulin sensitivity following a myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):1.

doi pubmed - Karwi QG, Uddin GM, Ho KL, Lopaschuk GD. Loss of metabolic flexibility in the failing heart. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;5:68.

doi pubmed - Hu YX, Qiu SL, Shang JJ, Wang Z, Lai XL. Pharmacological effects of botanical drugs on myocardial metabolism in chronic heart failure. Chin J Integr Med. 2024;30(5):458-467.

doi pubmed - Horowitz JD, Chirkov YY, Kennedy JA, Sverdlov AL. Modulation of myocardial metabolism: an emerging therapeutic principle. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;25(4):329-334.

doi pubmed - Honka H, Solis-Herrera C, Triplitt C, Norton L, Butler J, DeFronzo RA. Therapeutic manipulation of myocardial metabolism: JACC State-of-the-Art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(16):2022-2039.

doi pubmed - Foell D, Wittkowski H, Vogl T, Roth J. S100 proteins expressed in phagocytes: a novel group of damage-associated molecular pattern molecules. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(1):28-37.

doi pubmed - Shi S, Yi JL. S100A8/A9 promotes MMP-9 expression in the fibroblasts from cardiac rupture after myocardial infarction by inducing macrophages secreting TNFalpha. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(12):3925-3935.

doi pubmed - Chen TJ, Yeh YT, Peng FS, Li AH, Wu SC. S100A8/A9 enhances immunomodulatory and tissue-repairing properties of human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(20).

doi pubmed - Okonkwo DO, Puffer RC, Puccio AM, Yuh EL, Yue JK, Diaz-Arrastia R, Korley FK, et al. Point-of-care platform blood biomarker testing of glial fibrillary acidic protein versus S100 calcium-binding protein B for prediction of traumatic brain injuries: a transforming research and clinical knowledge in traumatic brain injury study. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37(23):2460-2467.

doi pubmed - Katashima T, Naruko T, Terasaki F, Fujita M, Otsuka K, Murakami S, Sato A, et al. Enhanced expression of the S100A8/A9 complex in acute myocardial infarction patients. Circ J. 2010;74(4):741-748.

doi pubmed - Volz HC, Laohachewin D, Seidel C, Lasitschka F, Keilbach K, Wienbrandt AR, Andrassy J, et al. S100A8/A9 aggravates post-ischemic heart failure through activation of RAGE-dependent NF-kappaB signaling. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107(2):250.

doi pubmed - Yuan JQ, Wang SM, Guo L. S100A9 promotes glycolytic activity in HER2-positive breast cancer to induce immunosuppression in the tumour microenvironment. Heliyon. 2023;9(2):e13294.

doi pubmed - Chen Y, Ouyang Y, Li Z, Wang X, Ma J. S100A8 and S100A9 in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2023;1878(3):188891.

doi pubmed - Muller I, Vogl T, Kuhl U, Krannich A, Banks A, Trippel T, Noutsias M, et al. Serum alarmin S100A8/S100A9 levels and its potential role as biomarker in myocarditis. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7(4):1442-1451.

doi pubmed - Jakobsson G, Papareddy P, Andersson H, Mulholland M, Bhongir R, Ljungcrantz I, Engelbertsen D, et al. Therapeutic S100A8/A9 blockade inhibits myocardial and systemic inflammation and mitigates sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):374.

doi pubmed - Zlotnik A, Yoshie O. The chemokine superfamily revisited. Immunity. 2012;36(5):705-716.

doi pubmed - Wu CL, Yin R, Wang SN, Ying R. A review of CXCL1 in cardiac fibrosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:674498.

doi pubmed - Wang L, Zhang YL, Lin QY, Liu Y, Guan XM, Ma XL, Cao HJ, et al. CXCL1-CXCR2 axis mediates angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and remodelling through regulation of monocyte infiltration. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(20):1818-1831.

doi pubmed - Sakamuri SS, Valente AJ, Siddesha JM, Delafontaine P, Siebenlist U, Gardner JD, Bysani C. TRAF3IP2 mediates aldosterone/salt-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;429:84-92.

doi pubmed - Guo S, Wu J, Zhou W, Liu X, Liu Y, Zhang J, Jia S, et al. Identification and analysis of key genes associated with acute myocardial infarction by integrated bioinformatics methods. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(15):e25553.

doi pubmed - Khatib-Massalha E, Bhattacharya S, Massalha H, Biram A, Golan K, Kollet O, Kumari A, et al. Lactate released by inflammatory bone marrow neutrophils induces their mobilization via endothelial GPR81 signaling. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3547.

doi pubmed - Redlich S, Ribes S, Schutze S, Eiffert H, Nau R. Toll-like receptor stimulation increases phagocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans by microglial cells. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:71.

doi pubmed - Savage CD, Lopez-Castejon G, Denes A, Brough D. NLRP3-inflammasome activating DAMPs stimulate an inflammatory response in glia in the absence of priming which contributes to brain inflammation after injury. Front Immunol. 2012;3:288.

doi pubmed - Dunn JLM, Kartchner LB, Stepp WH, Glenn LI, Malfitano MM, Jones SW, Doerschuk CM, et al. Blocking CXCL1-dependent neutrophil recruitment prevents immune damage and reduces pulmonary bacterial infection after inhalation injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2018;314(5):L822-L834.

doi pubmed - Hou CH, Chen PC, Liu JF. CXCL1 enhances COX-II expression in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts by CXCR2, PLC, PKC, and NF-kappaB signal pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;124(Pt B):110909.

doi pubmed - Korbecki J, Bosiacki M, Barczak K, Lagocka R, Chlubek D, Baranowska-Bosiacka I. The clinical significance and role of CXCL1 chemokine in gastrointestinal cancers. Cells. 2023;12(10).

doi pubmed - Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Cardioimmunology: the immune system in cardiac homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(12):733-744.

doi pubmed - Gubser PM, Bantug GR, Razik L, Fischer M, Dimeloe S, Hoenger G, Durovic B, et al. Rapid effector function of memory CD8+ T cells requires an immediate-early glycolytic switch. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(10):1064-1072.

doi pubmed - Prabhu SD, Frangogiannis NG. The biological basis for cardiac repair after myocardial infarction: from inflammation to fibrosis. Circ Res. 2016;119(1):91-112.

doi pubmed - Kong P, Cui ZY, Huang XF, Zhang DD, Guo RJ, Han M. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: signaling pathways and therapeutic intervention. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):131.

doi pubmed - Zhu Y, Xian X, Wang Z, Bi Y, Chen Q, Han X, Tang D, et al. Research progress on the relationship between atherosclerosis and inflammation. Biomolecules. 2018;8(3).

doi pubmed - Fossati G, Moulding DA, Spiller DG, Moots RJ, White MR, Edwards SW. The mitochondrial network of human neutrophils: role in chemotaxis, phagocytosis, respiratory burst activation, and commitment to apoptosis. J Immunol. 2003;170(4):1964-1972.

doi pubmed - Maratou E, Dimitriadis G, Kollias A, Boutati E, Lambadiari V, Mitrou P, Raptis SA. Glucose transporter expression on the plasma membrane of resting and activated white blood cells. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37(4):282-290.

doi pubmed - Rodriguez-Espinosa O, Rojas-Espinosa O, Moreno-Altamirano MM, Lopez-Villegas EO, Sanchez-Garcia FJ. Metabolic requirements for neutrophil extracellular traps formation. Immunology. 2015;145(2):213-224.

doi pubmed - Carbone F, Nencioni A, Mach F, Vuilleumier N, Montecucco F. Pathophysiological role of neutrophils in acute myocardial infarction. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110(3):501-514.

doi pubmed - Everts B, Amiel E, Huang SC, Smith AM, Chang CH, Lam WY, Redmann V, et al. TLR-driven early glycolytic reprogramming via the kinases TBK1-IKKvarepsilon supports the anabolic demands of dendritic cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(4):323-332.

doi pubmed - Rice CM, Davies LC, Subleski JJ, Maio N, Gonzalez-Cotto M, Andrews C, Patel NL, et al. Tumour-elicited neutrophils engage mitochondrial metabolism to circumvent nutrient limitations and maintain immune suppression. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5099.

doi pubmed - Mills EL, O'Neill LA. Reprogramming mitochondrial metabolism in macrophages as an anti-inflammatory signal. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46(1):13-21.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cardiology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.