| Cardiology Research, ISSN 1923-2829 print, 1923-2837 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cardiol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 16, Number 6, December 2025, pages 489-498

Anti-Oxidative Effect of Dapagliflozin, a Selective Sodium Glucose Transporter-2 Inhibitor, for Cardio-Renal Protection in Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction

Riku Tsudomea, Yasunori Suematsub, e, f, Kohei Tashiroa, Akihito Ideishia, Midori Miyazakic, Yuiko Yanod, Tadaaki Arimurab, Tetsuo Hiratab, Kanta Fujimia, Shin-ichiro Miuraa, e, f

aDepartment of Cardiology, Fukuoka University School of Medicine, Fukuoka, Japan

bDepartment of Cardiology, Fukuoka University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan

cDepartment of Clinical Laboratory and Transfusion, Fukuoka University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan

dMiyase Clinic, Fukuoka, Japan

eThese authors contributed equally to this work.

fCorresponding Authors: Shin-ichiro Miura, Department of Cardiology, Fukuoka University School of Medicine, Fukuoka, Japan; Yasunori Suematsu, Department of Cardiology, Fukuoka University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan

Manuscript submitted July 5, 2025, accepted August 16, 2025, published online December 20, 2025

Short title: Dapagliflozin’s Anti-Oxidative Effect in Heart Failure

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cr2109

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Selective sodium glucose transporter-2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) has cardio-renal protective effects via osmotic diuresis and natriuresis, and other pleiotropic effects, such as anti-oxidative, anti-fibrotic, and anti-senescence effects, have been suggested. However, those pleiotropic effects have not yet been fully elucidated in a clinical study.

Methods: We investigated the effects of SGLT2i in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Twenty-five HFrEF patients who were initially treated with dapagliflozin from 2021 to 2023 at Fukuoka University Hospital were enrolled and we investigated their baseline characteristics, medications, clinical laboratory examination findings, echocardiography findings, and additional pleiotropic serum markers before administration of dapagliflozin and 6 months later.

Results: The patients were 67.0 ± 13.6 years old, 64.0% were male, and their body mass index was 24.0 ± 4.5 kg/m2. Only four patients (16.0%) had diabetes mellitus. With regard to medications, 64.0%, 76.0%, and 60.0% were already taking renin-angiotensin aldosterone system inhibitors, beta-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, respectively, and these medications did not change significantly for 6 months. After treatment with dapagliflozin for 6 months, serum brain natriuretic peptide, left ventricular ejective function, hemoglobin, and urinary N-acetyl-β-D-glycosaminidase were significantly improved. In addition, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and oxidative stress markers including myeloperoxidase, matrix metalloproteinase-1, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 significantly improved, while anti-fibrosis and anti-senescence markers did not.

Conclusions: Dapagliflozin had anti-oxidative effects in patients with HFrEF, in addition to cardio-renal protective effects. These anti-oxidative effects could be related to the cardio-renal protective effects of SGLT2i, even in a clinical setting.

Keywords: Selective sodium glucose transporter-2 inhibitor; Anti-oxidative effect; Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Selective sodium glucose transporter-2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) is a class of antidiabetic agents that lower blood glucose by inhibiting renal glucose reabsorption [1]. Beyond glycemic control, SGLT2i has demonstrated beneficial effects in heart failure, attributable to natriuresis, osmotic diuresis, and potential pleiotropic actions [2]. Dapagliflozin, a type of SGLT2i, has been shown to have cardioprotective effects in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) [3], and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction [4]. Against this background, current guidelines for the treatment of heart failure now recommend the use of SGLT2i, regardless of the presence of type 2 diabetes or left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) [5]. Dapagliflozin also has renal protective effects [6]. However, the extrarenal effects of SGLT2i remain unclear.

Studies have indicated that SGLT2i reduces endothelial dysfunction in diabetic patients [7, 8], and several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this effect. These mechanisms include anti-oxidant properties [9-11], enhanced nitric oxide production [12, 13], and anti-inflammatory actions [14, 15]. However, the supporting evidence is primarily derived from animal and in vitro studies. In animal models, dapagliflozin has been shown to reduce markers associated with endothelial aging, such as senescence-associated β-galactosidase, p21, and p53 [13]. A comprehensive elucidation of these mechanisms could pave the way for the development of more effective therapeutic strategies for cardiovascular disease. In this study, we conducted an exploratory analysis of the effects of dapagliflozin in patients with HFrEF, focusing on a broad panel of pleiotropic markers to understand its potential non-glycemic benefits in a clinical setting.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study protocol

The protocol for this clinical study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Committee of Fukuoka University in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (#U19-07-012). This was a single-center, prospective cohort study. A total of 25 HFrEF patients who were initially treated with dapagliflozin 10 mg between June 2021 and June 2023 were included. We selected patients who were aged 20 years or older, of either gender, and who survived until discharge. Eligible subjects were investigated with respect to their baseline characteristics, medications, clinical laboratory examinations, echocardiography, and additional pleiotropic serum markers before the administration of dapagliflozin and 6 months later.

Baseline characteristics

Age, sex, body height, body weight, body mass index, blood pressure, underlying diseases, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease, including ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, and atrial fibrillation, were investigated. Body mass index was calculated as weight divided by height × height. With regard to medications, renin angiotensin aldosterone system inhibitors including angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, beta-blocker, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, pimobendan, calcium channel blocker, and diuretics were investigated.

Clinical laboratory examinations

We investigated the results of blood examinations before dapagliflozin treatment and after 6 months. White blood cell, red blood cell, hemoglobin, platelet, hematocrit, total protein, albumin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, ferritin, C-reactive protein (CRP), and brain natriuretic peptide were investigated. We also investigated the results of urine examinations, including N-acetyl-β-D-glycosaminidase, microalbumin, and liver-type fatty acid binding protein.

Echocardiography

We investigated the results of echocardiography before dapagliflozin administration and 6 months later. Left atrial dimension, aortic dimension, interventricular septum, left ventricular posterior wall, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension, left ventricular end-systolic dimension, LVEF, left ventricular end-diastolic volume, left ventricular end-systolic volume, ratio of early to late diastolic filling velocities, ratio of early diastolic filling velocity to early diastolic mitral annular velocity, and tricuspid regurgitation pressure gradient were investigated.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

To examine the pleiotropic effects of dapagliflozin, serum biomarkers were measured in duplicate following the manufacturers’ instructions. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were used for galectin-3 (Cat. #DGAL30, R&D Systems Inc.), procollagen type I C-terminal propeptide (Cat. #SEA570Hu, Cloud-Clone Corp.), procollagen type III N-terminal propeptide (Cat. #SEA573Hu, Cloud-Clone Corp.), endotrophin (Cat. #MBS1608767, MyBioSource), myeloperoxidase (MPO; Cat. #KR6631B, Immundiagnostik AG), and α-Klotho (Cat. #JP27998, IBL International).

Multiplex bead-based immunoassays (Luminex® MAGPIX® system, Luminex Corp., Austin, TX, USA) were used to quantify fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF-21) and growth differentiation factor-11 (GDF-11) (MILLIPLEX® MAP Human Adipokine Magnetic Bead Panel, Cat. #HAGE1MAG-20K-04, MilliporeSigma), as well as matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), MMP-2, and MMP-9 (MILLIPLEX® MAP Human MMP Magnetic Bead Panel 2, Cat. #HMMP2MAG-55K-03, MilliporeSigma).

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) at Fukuoka University (Fukuoka, Japan). Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data, and as the median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed data. For continuous variables, those with normal distributions were analyzed using the paired t-test, while those with non-normal distributions were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Categorical variables were analyzed using McNemar’s test for paired binary data. P values were two-sided and considered statistically significant if P < 0.05. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made given the exploratory nature of the study.

| Results | ▴Top |

Patient characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of all patients (n = 25). In this study group, the mean age was 67.0 ± 13.6 years and 64.0% were male. Approximately half of the patients had hypertension and dyslipidemia. Only four patients (16.0%) had diabetes mellitus and were not being treated with SGLT2i. With regard to cardiovascular disease, the percentages of patients with ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, and atrial fibrillation were 36.0%, 24.0%, and 52.0%, respectively. Table 2 shows the changes in vital signs and medications after treatment with dapagliflozin for 6 months. Body weight and body mass index were significantly reduced and blood pressure did not show significant changes under treatment with dapagliflozin. Excluding dapagliflozin, there were no significant changes in the medications used for 6 months.

Click to view | Table 1. Baseline Characteristics (n = 25) |

Click to view | Table 2. Changes in Vital Signs and Medications After Treatment With Dapagliflozin for 6 Months (n = 25) |

Changes in the results of biochemical examinations after treatment with dapagliflozin for 6 months

Table 3 shows the changes in biochemical examination results between before and after treatment with dapagliflozin. Red blood cells, hemoglobin, hematocrit, total protein, and albumin all significantly increased after treatment with dapagliflozin. On the other hand, white blood cells, alanine aminotransferase, ferritin, CRP, brain natriuretic peptide, urinary N-acetyl-β-D-glycosaminidase, and urinary creatinine significantly decreased after treatment.

Click to view | Table 3. Changes in the Results of Biochemical Examinations |

Changes in transthoracic echocardiography after treatment with dapagliflozin for 6 months

Table 4 shows the changes in transthoracic echocardiography parameters between before and after treatment with dapagliflozin. After treatment, left ventricular end-systolic dimension, end-diastolic volume, end-systolic volume, the ratio of early to late diastolic filling velocities, the ratio of early diastolic filling velocity to early diastolic mitral annular velocity, and tricuspid regurgitation pressure gradient significantly decreased. LVEF was significantly increased.

Click to view | Table 4. Changes in Transthoracic Echocardiography Findings |

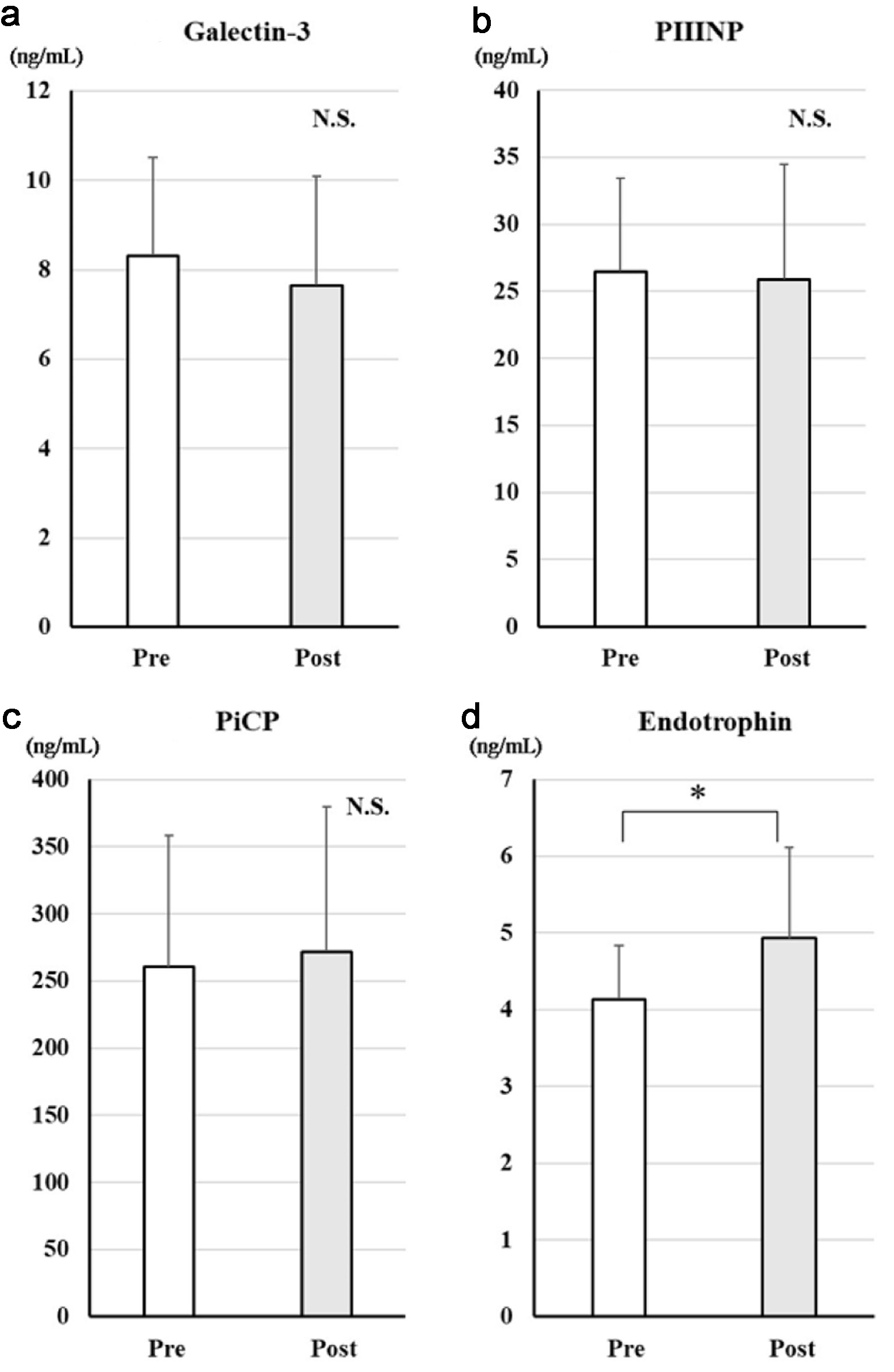

Changes in serum markers of fibrosis after treatment with dapagliflozin for 6 months

Figure 1 shows the changes in serum markers of fibrosis between before and after dapagliflozin. There were no significant decreases in galectin-3, procollagen I C-terminal propeptide, or procollagen III N-terminal propeptide after treatment. Endotrophin levels significantly increased. On the other hand, endotrophin levels significantly increased.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Changes in serum markers of fibrosis after treatment with dapagliflozin for 6 months. Changes in galectin-3 (a), PIIINP (b), PiCP (c), and endotrophin (d) before and after treatment with dapagliflozin. *Significant differences between before and after treatment. PIIINP: procollagen type III N-terminal propeptide; PiCP: procollagen type I C-terminal propeptide; NS: not significant. |

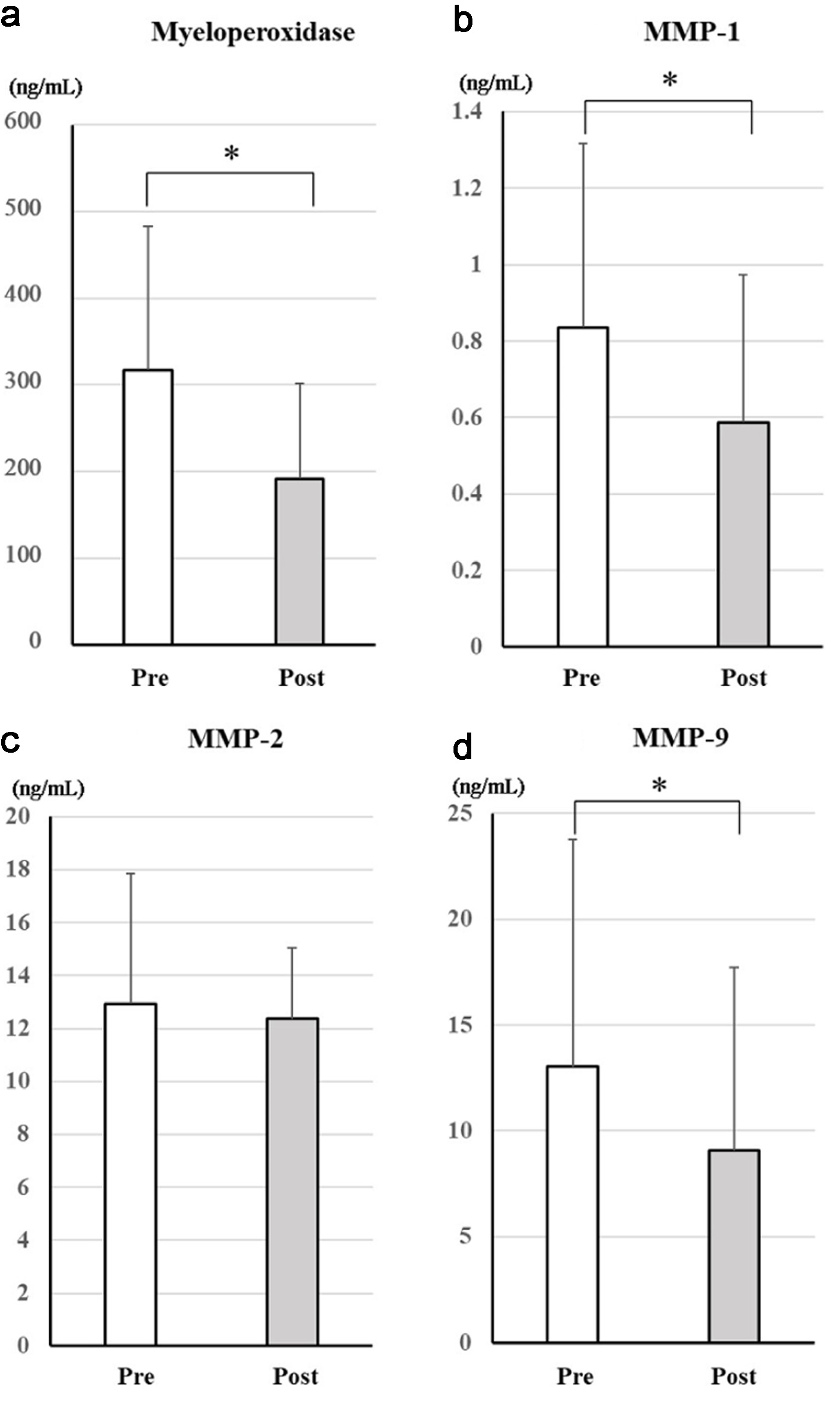

Changes in serum markers of anti-oxidative effects after treatment with dapagliflozin for 6 months

Figure 2 shows the changes in serum markers of anti-oxidative effects between before and after treatment with dapagliflozin. After treatment, MPO (mean difference: +115 ng/mL, 95% confidence interval (CI): 39 to 191 ng/mL, P = 0.0047), MMP-1 (mean difference: +306 ng/mL, 95% CI: 124 to 488 ng/mL, P = 0.0021), and MMP-9 (mean difference: +6,196 ng/mL, 95% CI: 670 to 11,721 ng/mL, P = 0.029) levels significantly decreased, whereas MMP-2 (mean difference: +723 ng/mL, 95% CI: -1,280 to 2,726 ng/mL, P = 0.46) showed no significant change.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Changes in serum markers of antioxidative effects after treatment with dapagliflozin for 6 months. Changes in myeloperoxidase (a), MMP-1 (b), MMP-2 (c), and MMP-9 (d) between before and after treatment with dapagliflozin. *Significant differences between before and after treatment. MMP-1: matrix metalloproteinase-1; MMP-2: matrix metalloproteinase-2; MMP-9: matrix metalloproteinase-9; NS: not significant. |

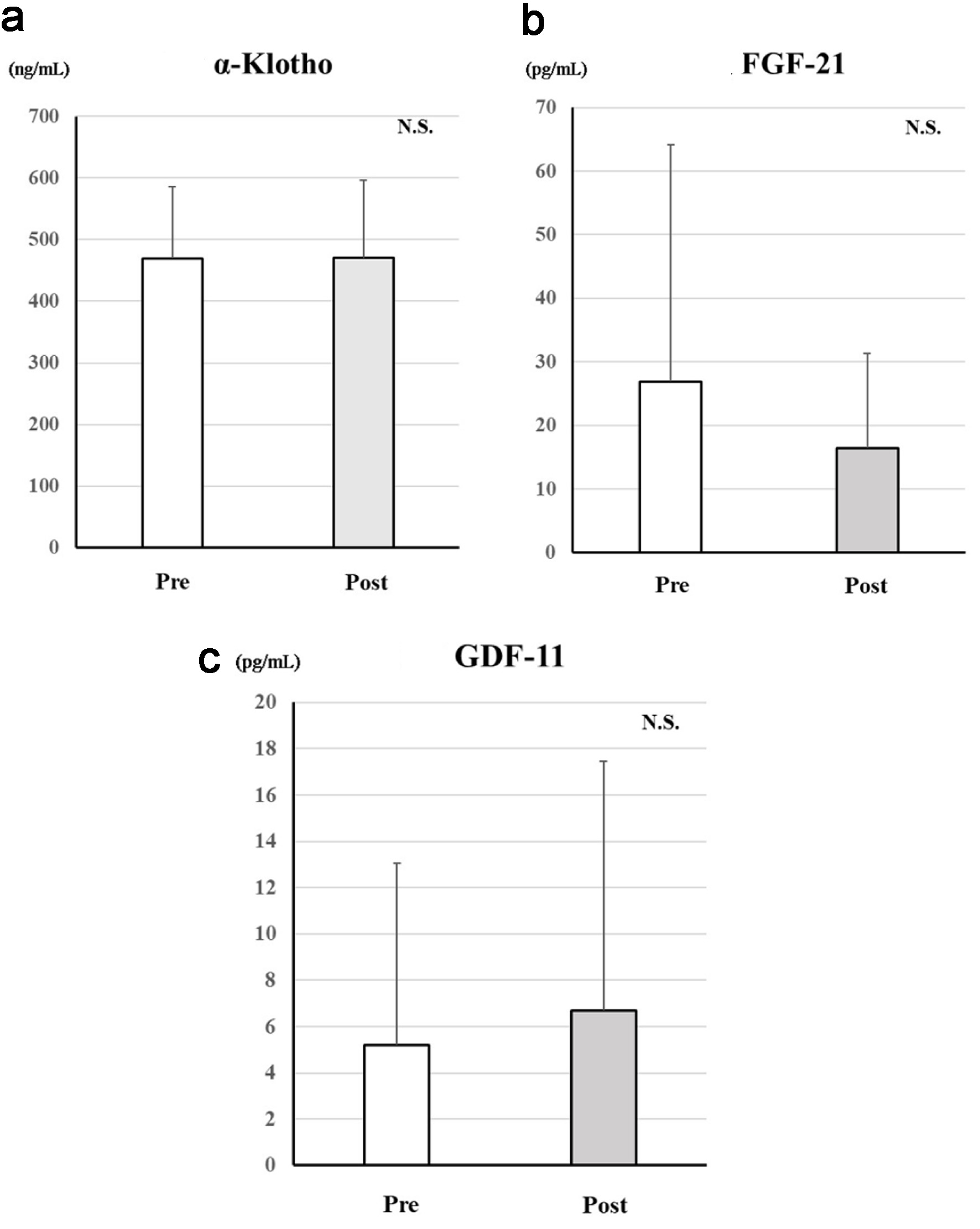

Changes in serum age-related proteins after treatment with dapagliflozin for 6 months

Figure 3 shows the changes in age-related proteins between before and after treatment with dapagliflozin. There were no significant changes in these markers.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Changes in serum age-related proteins after treatment with dapagliflozin for 6 months. Changes in α-Klotho (a), FGF-21 (b), and GDF-11 (c) between before and after treatment with dapagliflozin. *Significant differences between before and after treatment. FGF-21: fibroblast growth factor-21; GDF-11: growth differentiation factor-11; NS: not significant. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In this study, treatment with dapagliflozin for 6 months had anti-oxidative effects in patients with HFrEF, in addition to cardio-renal protective effects. Anti-oxidative effects could be related to the cardio-renal protective effects of SGLT2i, even in clinical setting.

In this study, we confirmed that the improvements of 6 months of dapagliflozin treatment in patients with HFrEF were associated with improvements in cardiac function, reductions in oxidative stress markers, and renal protective effects. SGLT2i has been shown to have cardioprotective effects [16-18]. Treatment with empagliflozin for 6 months significantly improved left ventricular volume and LVEF in non-diabetic HFrEF patients [19]. The DAPA-MODA study showed that dapagliflozin improved left atrial and ventricular remodeling in chronic heart failure patients [20]. Our results were consistent with these previous reports.

We observed decreases in markers of proximal, tubule function, such as urinary N-acetyl-β-D-glycosaminidase and liver-type fatty acid-binding protein, confirming renal-protective effects. Although creatinine levels did not change, this may reflect recovery from the initial gap [21]. The increase in hematocrit might indicate an improvement in renal oxygenation and recovery of erythropoietin production. Previous studies have suggested that the process of glucose reabsorption from the renal tubules consumes a lot of energy, leading to decreased renal oxygen pressure [22, 23]. It has been reported that SGLT2i suppresses sodium and glucose reabsorption, improves renal oxygen supply, and subsequently recovers erythropoietin production, leading to an increased hematocrit level [24, 25]. Also, our study showed significant increases in red blood cells and hemoglobin, suggesting improved erythropoietin production [26]. The increase in hematocrit associated with SGLT2i is considered to be an important mediator of the cardiorenal-protective effects [27, 28].

SGLT2i has been reported to exert cardioprotective effects through anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant mechanisms [29, 30]. Excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by mitochondria and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase damage cardiomyocytes, disrupting excitation-contraction coupling and intracellular signaling. Persistent ROS elevation leads to contractile dysfunction, structural remodeling, and progression of heart failure [31]. Oxidative stress and chronic inflammation contribute to vascular endothelial dysfunction and vascular aging. ROS impair endothelial progenitor cells, reduce nitric oxide bioavailability, and diminish endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Additionally, ROS increase the expression of vasoactive molecules such as MMPs and vascular endothelial growth factor, promoting vascular remodeling [32].

Reducing oxidative stress helps prevent cardiovascular disease progression, particularly in the development of heart failure [33, 34]. In our study, MPO, a marker of oxidative stress, was significantly reduced following treatment with dapagliflozin. We also observed significant decreases in MMP-1 and MMP-9. MMPs degrade extracellular matrix proteins and are involved in inflammatory processes. ROS are known to enhance MMP-1 transcription [35], and the reduction in MMP-1 observed in our study suggests that SGLT2i can attenuate oxidative stress. MMP-9 has been associated with adverse post-myocardial infarction remodeling [36], and its reduction may contribute to the cardioprotective effects of SGLT2i. Although MMP-2 has been linked to inflammation, immune responses, and impaired cardiac function [37], no significant change was detected in our study.

Inflammation is also implicated in the pathogenesis of heart failure [38]. Previous clinical studies have demonstrated a reduction in CRP in diabetic patients treated with dapagliflozin [39]. In our study, significant reductions in both white blood cell count and CRP were observed after treatment with dapagliflozin, supporting the anti-inflammatory effects of SGLT2i. A major strength of our study is that we have demonstrated the anti-oxidant effects of SGLT2i in humans. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that systemic glucose excretion contributed to these effects.

In this study, there were no significant decreases in markers of fibrosis, and endotrophin even increased. Previous reports have described the antifibrotic effects of SGLT2i, but these were based on cell and animal experiments and have certain limitations. One study reported that inhibition of the transforming growth factor-β1/Smad signaling pathway suppresses cardiac fibrosis [40]. Another study showed that empagliflozin inhibited the transforming growth factor-β1/Smad pathway and activated the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/anti-oxidant response element signaling pathway, thereby suppressing oxidative stress and fibrosis [41]. In a clinical study, canagliflozin did not have antifibrotic effects [42]. We measured the age-related protein α-Klotho, FGF-21, and GDF-11, but no significant differences were observed. The unexpected increase in endotrophin should be interpreted with caution. It may reflect the short observation period, heterogeneity of the patient population, or fluctuation through pathophysiological pathways independent of those related to oxidative stress. Given the current data, these possibilities cannot be excluded, and further studies with longer follow-up and more homogeneous cohorts are warranted.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was limited because it was from just one center and included only a small number of enrolled patients. Despite this, our exploratory research showed meaningful results. Second, the study period may have been too short to detect other pleiotropic effects, such as those on fibrosis and longevity. Further research will be needed.

Conclusions

Dapagliflozin showed anti-oxidative effects in patients with HFrEF, in addition to cardio-renal protective effects. These anti-oxidative effects may be related to the cardio-renal protective effects of SGLT-2i, even in a clinical setting.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it was a single-center investigation with a small sample size (n = 25), which limits statistical power and generalizability. Second, the absence of a control group makes it difficult to attribute causality solely to dapagliflozin, as effects may have been influenced by background medical therapy, weight loss, or regression to the mean. Third, multiple biomarker and echocardiographic comparisons were made without adjustment for multiple testing, raising the risk of type I error. Finally, the observation period of 6 months may be too short to detect changes in certain pleiotropic pathways such as fibrosis or cellular senescence. Furthermore, long-term, larger-scale studies are warranted to determine whether the observed effects persist over time and whether their magnitude increases with prolonged treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kanji Nakai, Sayo Tomita, and Satomi Abe for their excellent technical assistance.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Author Contributions

RT and YS contributed to the conception and design of the work. KT, AI, MM, YY, TA, TH, and KF were responsible for the acquisition of data and cleaned the data. RT and YS performed all data analyses. RT and YS drafted the manuscript. SM checked statistical analysis and revised the manuscript critically. SM critically reviewed the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Vallon V, Thomson SC. Targeting renal glucose reabsorption to treat hyperglycaemia: the pleiotropic effects of SGLT2 inhibition. Diabetologia. 2017;60(2):215-225.

doi pubmed - Mondal S, Pramanik S, Khare VR, Fernandez CJ, Pappachan JM. Sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and heart disease: current perspectives. World J Cardiol. 2024;16(5):240-259.

doi pubmed - McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Kober L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, Ponikowski P, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):1995-2008.

doi pubmed - Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Jhund P, de Boer RA, Hernandez AF, Inzucchi SE, Kosiborod MN, et al. Time to clinical benefit of dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction: a prespecified secondary analysis of the DELIVER randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(12):1259-1263.

doi pubmed - Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, Deswal A, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(18):e895-e1032.

doi pubmed - Mavrakanas TA, Tsoukas MA, Brophy JM, Sharma A, Gariani K. SGLT-2 inhibitors improve cardiovascular and renal outcomes in patients with CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):15922.

doi pubmed - Tanaka A, Shimabukuro M, Machii N, Teragawa H, Okada Y, Shima KR, Takamura T, et al. Effect of Empagliflozin on Endothelial Function in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: Results from the Multicenter, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind EMBLEM Trial. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(10):e159-e161.

doi pubmed - Shigiyama F, Kumashiro N, Miyagi M, Ikehara K, Kanda E, Uchino H, Hirose T. Effectiveness of dapagliflozin on vascular endothelial function and glycemic control in patients with early-stage type 2 diabetes mellitus: DEFENCE study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):84.

doi pubmed - Ganbaatar B, Fukuda D, Shinohara M, Yagi S, Kusunose K, Yamada H, Soeki T, et al. Empagliflozin ameliorates endothelial dysfunction and suppresses atherogenesis in diabetic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;875:173040.

doi pubmed - Kuno A, Kimura Y, Mizuno M, Oshima H, Sato T, Moniwa N, Tanaka M, et al. Empagliflozin attenuates acute kidney injury after myocardial infarction in diabetic rats. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):7238.

doi pubmed - Du S, Shi H, Xiong L, Wang P, Shi Y. Canagliflozin mitigates ferroptosis and improves myocardial oxidative stress in mice with diabetic cardiomyopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1011669.

doi pubmed - Ma L, Zou R, Shi W, Zhou N, Chen S, Zhou H, Chen X, et al. SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin reduces endothelial dysfunction and microvascular damage during cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury through normalizing the XO-SERCA2-CaMKII-coffilin pathways. Theranostics. 2022;12(11):5034-5050.

doi pubmed - Zhou Y, Tai S, Zhang N, Fu L, Wang Y. Dapagliflozin prevents oxidative stress-induced endothelial dysfunction via sirtuin 1 activation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;165:115213.

doi pubmed - Alsereidi FR, Khashim Z, Marzook H, Gupta A, Al-Rawi AM, Ramadan MM, Saleh MA. Targeting inflammatory signaling pathways with SGLT2 inhibitors: Insights into cardiovascular health and cardiac cell improvement. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2024;49(5):102524.

doi pubmed - Cooper S, Teoh H, Campeau MA, Verma S, Leask RL. Empagliflozin restores the integrity of the endothelial glycocalyx in vitro. Mol Cell Biochem. 2019;459(1-2):121-130.

doi pubmed - Tanaka H, Hirata KI. Potential impact of SGLT2 inhibitors on left ventricular diastolic function in patients with diabetes mellitus. Heart Fail Rev. 2018;23(3):439-444.

doi pubmed - Pastore MC, Stefanini A, Mandoli GE, Piu P, Diviggiano EE, Iuliano MA, Carli L, et al. Dapagliflozin effects on cardiac deformation in heart failure and secondary clinical outcome. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2024;17(12):1399-1408.

doi pubmed - Cloninger CR, von Knorring AL, Sigvardsson S, Bohman M. Symptom patterns and causes of somatization in men: II. Genetic and environmental independence from somatization in women. Genet Epidemiol. 1986;3(3):171-185.

doi pubmed - Santos-Gallego CG, Vargas-Delgado AP, Requena-Ibanez JA, Garcia-Ropero A, Mancini D, Pinney S, Macaluso F, et al. Randomized trial of empagliflozin in nondiabetic patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(3):243-255.

doi pubmed - Pascual-Figal DA, Zamorano JL, Domingo M, Morillas H, Nunez J, Cobo Marcos M, Riquelme-Perez A, et al. Impact of dapagliflozin on cardiac remodelling in patients with chronic heart failure: The DAPA-MODA study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25(8):1352-1360.

doi pubmed - Heerspink HJL, Cherney DZI. Clinical implications of an acute dip in eGFR after SGLT2 inhibitor initiation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(8):1278-1280.

doi pubmed - Gilbert RE. SGLT2 inhibitors: beta blockers for the kidney? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(10):814.

doi pubmed - Sano M, Takei M, Shiraishi Y, Suzuki Y. Increased hematocrit during sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor therapy indicates recovery of tubulointerstitial function in diabetic kidneys. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8(12):844-847.

doi pubmed - Dharia A, Khan A, Sridhar VS, Cherney DZI. SGLT2 inhibitors: the sweet success for kidneys. Annu Rev Med. 2023;74:369-384.

doi pubmed - Heerspink HJL, Kosiborod M, Inzucchi SE, Cherney DZI. Renoprotective effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors. Kidney Int. 2018;94(1):26-39.

doi pubmed - Lambers Heerspink HJ, de Zeeuw D, Wie L, Leslie B, List J. Dapagliflozin a glucose-regulating drug with diuretic properties in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(9):853-862.

doi pubmed - Yanai H, Katsuyayama H. A possible mechanism for renoprotective effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor: elevation of erythropoietin production. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(2):178-179.

doi pubmed - Sano M, Goto S. Possible mechanism of hematocrit elevation by sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and associated beneficial renal and cardiovascular effects. Circulation. 2019;139(17):1985-1987.

doi pubmed - Li FF, Gao G, Li Q, Zhu HH, Su XF, Wu JD, Ye L, et al. Influence of dapagliflozin on glycemic variations in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:5347262.

doi pubmed - Pignatelli P, Baratta F, Buzzetti R, D'Amico A, Castellani V, Bartimoccia S, Siena A, et al. The Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors reduce platelet activation and thrombus formation by lowering NOX2-related oxidative stress: a pilot study. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11(10):1878.

doi pubmed - Liu L, Ni YQ, Zhan JK, Liu YS. The role of SGLT2 inhibitors in vascular aging. Aging Dis. 2021;12(5):1323-1336.

doi pubmed - Griendling KK, Camargo LL, Rios FJ, Alves-Lopes R, Montezano AC, Touyz RM. Oxidative stress and hypertension. Circ Res. 2021;128(7):993-1020.

doi pubmed - Keith M, Geranmayegan A, Sole MJ, Kurian R, Robinson A, Omran AS, Jeejeebhoy KN. Increased oxidative stress in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(6):1352-1356.

doi pubmed - Ichihara S, Yamada Y, Ichihara G, Kanazawa H, Hashimoto K, Kato Y, Matsushita A, et al. Attenuation of oxidative stress and cardiac dysfunction by bisoprolol in an animal model of dilated cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350(1):105-113.

doi pubmed - Kar S, Subbaram S, Carrico PM, Melendez JA. Redox-control of matrix metalloproteinase-1: a critical link between free radicals, matrix remodeling and degenerative disease. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;174(3):299-306.

doi pubmed - de Castro Bras LE, Cates CA, DeLeon-Pennell KY, Ma Y, Iyer RP, Halade GV, Yabluchanskiy A, et al. Citrate synthase is a novel in vivo matrix metalloproteinase-9 substrate that regulates mitochondrial function in the postmyocardial infarction left ventricle. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21(14):1974-1985.

doi pubmed - Wang GY, Bergman MR, Nguyen AP, Turcato S, Swigart PM, Rodrigo MC, Simpson PC, et al. Cardiac transgenic matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression directly induces impaired contractility. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69(3):688-696.

doi pubmed - Murphy SP, Kakkar R, McCarthy CP, Januzzi JL, Jr. Inflammation in heart failure: JACC State-of-the-Art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(11):1324-1340.

doi pubmed - Ferrannini E, Ramos SJ, Salsali A, Tang W, List JF. Dapagliflozin monotherapy in type 2 diabetic patients with inadequate glycemic control by diet and exercise: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(10):2217-2224.

doi pubmed - Chen X, Yang Q, Bai W, Yao W, Liu L, Xing Y, Meng C, et al. Dapagliflozin attenuates myocardial fibrosis by inhibiting the TGF-beta1/Smad signaling pathway in a normoglycemic rabbit model of chronic heart failure. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:873108.

doi pubmed - Li C, Zhang J, Xue M, Li X, Han F, Liu X, Xu L, et al. SGLT2 inhibition with empagliflozin attenuates myocardial oxidative stress and fibrosis in diabetic mice heart. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):15.

doi pubmed - Januzzi JL, Jr., Butler J, Jarolim P, Sattar N, Vijapurkar U, Desai M, Davies MJ. Effects of canagliflozin on cardiovascular biomarkers in older adults with type 2 diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(6):704-712.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cardiology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.