| Cardiology Research, ISSN 1923-2829 print, 1923-2837 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cardiol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 16, Number 5, October 2025, pages 413-420

Comparative Outcomes of Alternative Access Site Versus Lithotripsy-Assisted Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Single-Center Retrospective Study

Gabriel Ramosa, Grant DeLozierb, Ryan Ullibarrib, Alden Miletob, Nicholas Ierovantec, d, Yassir Nawazc

aDepartment of Medicine, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA, USA

bDepartment of Medicine, Geisinger Medical System, Scranton, PA, USA

cDepartment of Cardiology, Geisinger Medical System, Scranton, PA, USA

dCorresponding Author: Nicholas Ierovante, Department of Cardiology, Geisinger Medical System, Scranton, PA, USA

Manuscript submitted July 15, 2025, accepted September 10, 2025, published online October 10, 2025

Short title: Alternative Access vs. Lithotripsy TAVR Outcomes

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cr2115

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has emerged as a primary therapeutic option for patients with severe aortic stenosis across all surgical risk categories. Alternative access site (AAS) routes are often used in patients unsuitable for standard transfemoral (TF) approach, though intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) provides novel remedies to traditionally “unsuitable” patients. The objectives of our study were to compare outcomes between AAS TAVR placement and lithotripsy-assisted TF TAVR.

Methods: The authors analyzed 60 patients who underwent TAVR between 2019 and 2022 (41 with alternative access, 19 with lithotripsy) at a single US site. Primary outcomes included procedural success, adverse events at 1 month and 1 year, length of stay, and 3-year mortality.

Results: The data trended towards higher 1-month adverse outcomes in the alternative access patients compared to TF lithotripsy patients (17.1% (95% confidence interval (CI): 8.5% - 31.3%) vs. 0% (95% CI: 0.0% - 16.8%); P = 0.09), while 1-year adverse outcomes were similar (AAS 12.2% (95% CI: 5.3% - 25.5%) vs. IVL 15.8% (95% CI: 5.5% - 37.6%); P = 0.70), and 3-year mortality (19.5% vs. 21.1%) were similar between groups. Median length of stay was 3 days for both groups.

Conclusions: Lithotripsy-assisted TF TAVR demonstrated a statistically insignificant trend toward short-term major adverse events with comparable 1-year morbidity and 3-year mortality to alternative access approaches. These findings may support lithotripsy as a viable option for patients with challenging vascular anatomy rather than the more traditional use of AAS in these settings. However, more extensive research is necessary for appropriate statistical power to prove superiority rather than equivocality alone.

Keywords: TAVR; Alternative access; Lithotripsy; Vascular complications; Structural heart intervention

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has revolutionized the treatment of severe aortic stenosis, with the transfemoral (TF) approach preferred due to its established safety profile and superior outcomes compared to surgical aortic valve replacement [1-3]. However, severe peripheral artery disease, small vessel diameter, or excessive tortuosity can preclude TF access in roughly 5-15% of patients [4, 5]. Two strategies have emerged for these challenging cases: alternative access sites (AAS; transcarotid, transcaval, transapical, direct aortic, etc.) and intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) of the aortoiliac arterial system to preserve TF access [6, 7]. IVL uses sonic pressure waves to fracture calcified plaques, potentially restoring vessel compliance, facilitating large-bore access [8, 9].

Recent registry data demonstrate both approaches are feasible, with alternative access showing acceptable outcomes and lithotripsy enabling TF TAVR in over 90% of attempted cases [10, 11]. However, despite growing adoption of both techniques, no direct comparative data exist to guide clinical decision-making. A recent large US database study specifically identified the absence of direct comparative data and called for studies delineating optimal use criteria for IVL-TAVR versus alternative access [12]. This study provides the first head-to-head comparison of these approaches, offering real-world outcome data to inform multidisciplinary heart team decisions.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This single-center, retrospective study was conducted within the Geisinger Health System. We reviewed data from patients who underwent TAVR between 2019 and 2022. Patients were included if they received either AAS TAVR or lithotripsy-assisted TF TAVR due to challenging iliofemoral anatomy that precluded standard TF access, following evaluation and procedural selection at discretion of the multidisciplinary heart team, consisting of interventional cardiology, cardiac surgery, advanced imaging, and anesthesiology.

Patients were categorized into two groups: 1) AAS group: patients who underwent TAVR via transapical, direct aortic, transcarotid, transaxillary, or trans-subclavian approaches; and 2) Lithotripsy group: patients who underwent TF TAVR after IVL preparation of the iliofemoral vessels. No crossover cases occurred where lithotripsy failed requiring bailout alternative access.

Procedural stratification and selection for IVL vs. AAS was individualized and performed following initial evaluation of suitability for surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) vs. TAVR, based on patient needs and characteristics. Salient anatomic findings of pre-procedural imaging were a primary stratification tool and included at least a standardized transthoracic echocardiography, contrast-enhanced, electrocardiogram (ECG)-synchronized computed tomography (CT) for annular sizing, coronary height and sinus dimensions, and iliofemoral access assessment, including minimum lumen diameter, calcium burden and distribution, and tortuosity, in accordance with professional-society guidance [13, 14]. These were taken alongside the results of routine assessment of frailty by experienced providers using validated tools, patient comorbidity, and patient preference.

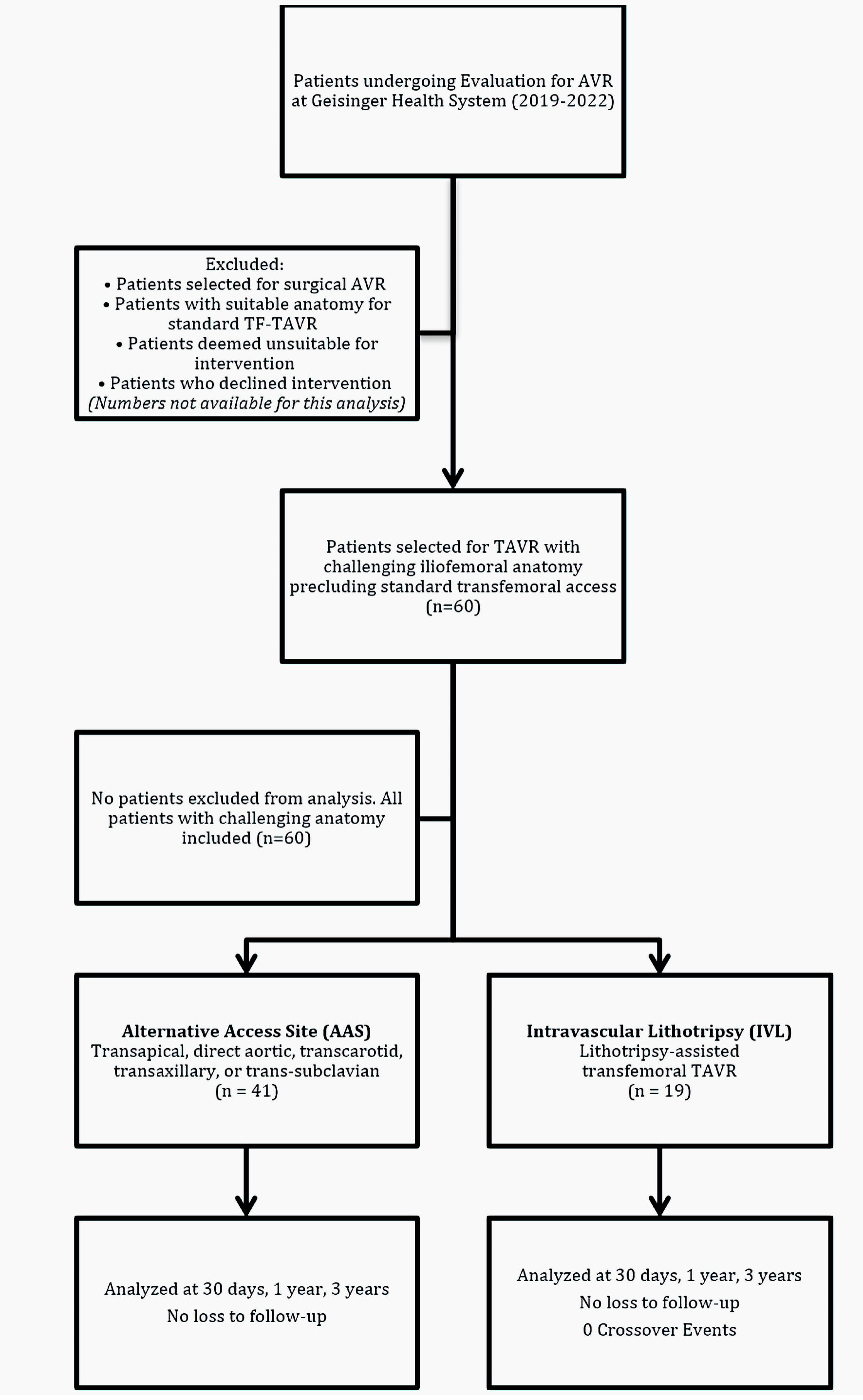

Following selection for TAVR, patients underwent IVL-assisted TF access when CT showed focal or segmental, near-circumferentially calcified lesions that would otherwise preclude safe large-bore sheath passage without modification. TF access was preferred, and an alternative access method was chosen only when disease was diffuse or throughout a long vascular segment, tortuosity was severe, or the anticipated post-modification lumen was likely to remain below recommended sheath requirements, per professional-society guidance [6, 15]. Vessel diameter, calcification severity, and tortuosity were not abstracted empirically in this study. The study cohort and group allocation are illustrated in Figure 1.

Click for large image | Figure 1. STROBE flow diagram demonstrating cohort derivation, group allocation, and follow-up completion for the comparative analysis of alternative access site versus lithotripsy-assisted transfemoral TAVR. TAVR: transcatheter aortic valve replacement; TF: transfemoral. |

Primary operators performing these procedures were board-certified and fellowship-trained interventional cardiologists working alongside cardiothoracic surgeons across the Geisinger Health System. collectively, the operator group has performed > 2,000 TAVR procedures. Programmatic standards and credentialing align with the operator and institutional recommendations of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI)/Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) for the performance of TAVR [16].

Primary outcomes included procedural success (successful valve deployment without conversion to surgery), adverse outcomes at 1 month and 1 year post-procedure, length of stay (LOS, total and post-procedure), and all-cause mortality at 3 years. Total LOS was defined as admission-to-discharge. Post-procedure LOS was defined a priori as the time from the TAVR procedure timestamp to discharge. Adverse outcomes were defined as myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischemic attack, need for pacemaker implantation, major bleeding, endocarditis, or major vascular complications according to Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 definitions.

Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were described using means and standard deviations for normally distributed data and medians and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed data. Comparisons between groups were performed using Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test for categorical variables, as appropriate. For continuous variables, t-tests were used for normally distributed data and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for non-normally distributed data. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For binary outcomes (30-day and 1-year adverse events, 30-day rehospitalization, and 3-year all-cause mortality), two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Wilson score intervals with continuity correction to handle small samples and extreme proportions. Given the small sample and low event counts, multivariable or propensity modeling was considered underpowered and at risk of overfitting and was not performed. All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration and the responsible institution on human subjects. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Geisinger Medical Center approved the study and waived the requirement for individual patient consent due to the retrospective nature of the study.

| Results | ▴Top |

Patient characteristics

The study included 60 patients: 41 in the AAS group and 19 in the lithotripsy group. Mean age was similar between groups (AAS: 77.3 ± 7.83 years; lithotripsy: 78.1 ± 6.92 years; P = 0.69). Both groups showed a male predominance (AAS: 68.3%; lithotripsy: 73.7%). All patients were White. Baseline characteristics and outcomes are summarized in Table 1. The study cohort allocation is illustrated in Figure 1.

Click to view | Table 1. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of Alternative Access Site (AAS) Versus Lithotripsy-Assisted Transfemoral TAVR |

LOS

The median total LOS was 3 days for both groups (IQR: 2 - 6 days for AAS, 1 - 11 days for lithotripsy; P = 0.72). The median post-procedure LOS was 2 days for both groups (IQR: 1 - 3 days; P = 0.37).

Short-term outcomes

At 1 month post-procedure, the AAS group showed a trend toward higher adverse outcomes compared to the lithotripsy group (AAS 17.1% (95% CI: 8.5% - 31.3%) vs. IVL 0% (95% CI: 0.0% - 16.8%); P = 0.09). Adverse outcomes in the AAS group included significant vascular complications (2.4%), major bleeding (4.9%), new pacemaker insertion (4.9%), paravalvular leak (2.4%), and stroke with major vascular complication (2.4%). Event counts by category are shown in Table 1.

Long-term outcomes

At 1 year post-procedure, adverse outcome rates were similar between groups (AAS 12.2% (95% CI: 5.3% - 25.5%) vs. IVL 15.8% (95% CI: 5.5% - 37.6%); P = 0.70).These included myocardial infarction (AAS: 4.9%, lithotripsy: 10.5%), major bleeding (AAS: 2.4%, lithotripsy: 5.3%), and new pacemaker insertion (AAS: 2.4%, lithotripsy: 0%), as outlined in Table 1.

Mortality

Three-year all-cause mortality rates were similar (AAS: 19.5% (95% CI: 10.2% - 34.0%) vs. lithotripsy: 21.1% (95% CI: 8.5% - 43.3%)). In the lithotripsy group, all deaths were cardiovascular-related, while in the AAS group, only 37.5% of deaths were cardiovascular-related.

Repeat hospitalization

The 30-day repeat hospitalization rate was 17.1% (95% CI: 8.5% - 31.3%) for the AAS group and 26.3% (95% CI: 11.8% - 48.8%) for IVL (P = 0.49).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This study represents the first direct comparison of AAS TAVR and lithotripsy-assisted TF TAVR, addressing a critical knowledge gap identified, but not previously addressed, in recent literature [12]. Our real-world analysis demonstrates that both approaches achieve excellent procedural success with comparable intermediate-term outcomes, while revealing interesting patterns in short-term complications.

The observation of fewer 30-day adverse events in the IVL-TF group (0% (95% CI: 0.0% - 16.8%)) versus the AAS group (17.1% (95% CI: 8.5% - 31.3%)) did not reach statistical significance and should be viewed as hypothesis-generating. These patterns are consistent with broader evidence that, when feasible, preserving TF access is associated with favorable early outcomes in meta-analyses comparing femoral versus non-femoral access [17, 18], and with registry data reporting low early-event rates after IVL-TF-TAVR [11]. Our 2.4% rate of major vascular complications in alternative-access cases mirrors early TF series that reported 3% to 4% vascular injuries despite smaller introducer sheaths [19]. However, it is important to note that the 30-day rehospitalization rate was numerically higher in the lithotripsy group (26.3% vs. 17.1%), suggesting a more complex short-term risk-benefit profile than initially apparent.

The convergence of outcomes at 1 year with similar event rates in both cohorts supports both strategies as viable long-term options for patients with challenging anatomy [18], though the level of confidence in calling the techniques equivalent prescriptively remains limited, given our investigation’s limitations. In line with longer-term literature across device platforms and with comparisons of TAVR to SAVR, durable outcomes likely reflect multiple influences - including patient selection, anatomic considerations, and operator/program experience - rather than access strategy alone [20, 21]. In this context, IVL-assisted TF can be considered a reasonable strategy to preserve TF access in borderline anatomy, while larger, adjusted studies are needed to determine whether early differences translate into durable clinical benefit (and to define when non-TF access remains preferable). Preserving TF access aligns with established advantages of TF-TAVR in appropriate candidates [17].

Context from contemporary registries and implementation studies further underscores potential system-level implications. Peripheral non-TF strategies (e.g., transcarotid, transaxillary) have demonstrated outcomes comparable to or better than transthoracic access and, in multiple series, shorter LOS [22-24], while optimized TF pathways, like those put forth by FAST-TAVI and FAST-TAVI II, reproducibly reduce LOS and support earlier discharge in appropriate patients [25, 26]. These external data provide context for our finding of similar LOS across groups and suggest that center-level pathway implementation and access strategy may influence LOS and costs independent of device platform, generating important optimization-oriented insights for programs exploring feasibility of any or all of these strategies. Moreover, administrative and registry data also suggest that transapical access is associated with longer LOS and higher costs compared with non-transapical approaches [27]. It is important to note that, while LOS was similar between groups, there was a wider total LOS distribution in the IVL cohort (IQR 1 - 11 vs. 2 - 6 days for AAS). Given that post-procedure LOS did not greatly differ between groups, this increased distribution most plausibly reflects additional pre-procedure days and could reflect time accrued secondary to interfacility transfer, pre-procedural optimization, or scheduling rather than prolonged recovery after TAVR. Our dataset did not capture reasons for pre-procedure days, so these largely speculative inferences should be interpreted cautiously. Nevertheless, the similar LOS and readmission rates between groups indicate that neither approach offers a clear advantage in health-system resource utilization in our cohort, which, in addition to insights regarding efficiency of stay discussed above, may be an important consideration for programs planning or expanding TAVR programs [4]. However, the ability to maintain TF access through lithotripsy may offer other advantages not captured in our endpoints, such as procedural duration and complexity, anesthesia requirements, and post-procedural care involvedness at each level of the provider team, each of which were not collected for this cohort, warranting formal evaluation.

The difference in mortality etiology between groups warrants further study. Notably, all deaths in the lithotripsy group were cardiovascular-related, compared to only 37.5% in the AAS group. Whether this reflects selection bias or the natural history of lithotripsy-treated patients with severe peripheral arterial disease remains unclear and deserves investigation in larger cohorts, much in the same way that differential outcomes in transcatheter vs. surgical valve replacement have been examined [21].

Study limitations

This pilot study has several important limitations. The single-center design and retrospective nature limit generalizability. The sample size, while providing the first comparative data in this field, limits statistical power for detecting differences between groups. Additionally, the statistical analyses employed were unadjusted, and only univariate comparisons were performed. Because the small sample size precluded robust multivariable or propensity-based adjustment, some amount of residual confounding is expected to influence these data. Detailed quantitative vessel characteristics were not systematically abstracted, which may limit direct reproducibility of our study. We acknowledge that the data not being reported hold back systems and providers from deriving functional cutoff values from this study; however, selection followed established professional society guidance for access strategy selection as is appropriate, alongside consideration of patient characteristics. The non-randomized design introduces potential selection bias, as selection for the approach employed was based on physician judgment and anatomical factors discussed above. It is important to note that all patients included in this analysis were White, which limits demographic representativeness and external generalizability. The study period (2019 - 2022) represents early experience with lithotripsy technology, and outcomes may improve with greater operator experience [16, 28]. Patient-level duration spent inpatient in pre- versus post-procedure was not captured, constraining interpretation of the wider total LOS range observed in the IVL group. Event rates should be interpreted with caution given wide CIs in small samples, and the study is underpowered to detect rare outcomes (e.g., stroke, cause-specific death). Anesthesia type, procedural duration, recovery metrics, and itemized costs were not collected, precluding efficiency and economic comparisons. These data are imperative for further investigations to provide comprehensive insights for health systems and operators, as they balance efficacy and outcomes data with health system- and patient-level cost incurred as they attempt to provide high-fidelity care to as many patients as possible. Long-term durability data beyond 3 years are not available.

Conclusions

This first comparative analysis of AAS TAVR versus lithotripsy-assisted TF TAVR demonstrates comparable procedural success and intermediate-term outcomes between approaches. The pattern of fewer short-term complications with lithotripsy, while not statistically significant in this pilot cohort, provides hypothesis-generating data supporting larger comparative studies. These real-world findings offer initial evidence to guide multidisciplinary heart team decision-making in patients with challenging vascular anatomy and highlight lithotripsy as a potentially viable strategy to expand TF TAVR eligibility.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Geisinger statisticians for their excellent analytic support.

Financial Disclosure

The authors have no relationships with industry to disclose. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

The IRB at Geisinger Medical Center waived the requirement for individual consent due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Author Contributions

GR: study design, data collection, data analysis, validation, manuscript writing, manuscript review/editing. GD, RU, and AM: study design, data collection, data analysis, methodology. NI: study supervision, study design, procedure performance, manuscript review/editing. YN: study supervision, manuscript review.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and appropriate institutional approvals.

Abbreviations

AAS: alternative access site; GCMC: Geisinger Community Medical Center; GMC: Geisinger Medical Center; GWV: Geisinger Wyoming Valley; IQR: interquartile range; SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement; IVL: intravascular lithotripsy; TAVR: transcatheter aortic valve replacement; TF: transfemoral

| References | ▴Top |

- Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, Pibarot P, Hahn RT, Genereux P, Kodali SK, et al. transcatheter aortic-valve replacement in low-risk patients at five years. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(21):1949-1960.

doi pubmed - Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, Mumtaz M, Gada H, O'Hair D, Bajwa T, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(18):1706-1715.

doi pubmed - Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, Milojevic M, Baldus S, Bauersachs J, Capodanno D, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(7):561-632.

doi pubmed - Grover FL, Vemulapalli S, Carroll JD, Edwards FH, Mack MJ, Thourani VH, Brindis RG, et al. 2016 annual report of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(10):1215-1230.

doi pubmed - Stub D, Lauck S, Lee M, Gao M, Humphries K, Chan A, Cheung A, et al. Regional systems of care to optimize outcomes in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(15):1944-1951.

doi pubmed - Sherwood M, Allen KB, Dahle TG, Devireddy CM, Gaca J, Garcia S, Grubb KJ, et al. SCAI expert consensus statement on alternative access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2025;4(3 Part A):102514.

doi pubmed - Linder M, Grundmann D, Kellner C, Demal T, Waldschmidt L, Bhadra O, Ludwig S, et al. Intravascular lithotripsy-assisted transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe iliofemoral calcifications: expanding transfemoral indications. J Clin Med. 2024;13(5).

doi pubmed - Ali ZA, Brinton TJ, Hill JM, Maehara A, Matsumura M, Karimi Galougahi K, Illindala U, et al. Optical coherence tomography characterization of coronary lithoplasty for treatment of calcified lesions: first description. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(8):897-906.

doi pubmed - Hill JM, Kereiakes DJ, Shlofmitz RA, Klein AJ, Riley RF, Price MJ, Herrmann HC, et al. Intravascular lithotripsy for treatment of severely calcified coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(22):2635-2646.

doi pubmed - Lu H, Monney P, Hullin R, Fournier S, Roguelov C, Eeckhout E, Rubimbura V, et al. Transcarotid access versus transfemoral access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:687168.

doi pubmed - Nardi G, De Backer O, Saia F, Sondergaard L, Ristalli F, Meucci F, Stolcova M, et al. Peripheral intravascular lithotripsy for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a multicentre observational study. EuroIntervention. 2022;17(17):e1397-e1406.

doi pubmed - Imran HM, Has P, Kassis N, Shippey E, Elkaryoni A, Gordon PC, Sharaf BL, et al. Characteristics, trends, and outcomes of intravascular lithotripsy-assisted transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement in United States. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17(20):2367-2376.

doi pubmed - Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, 3rd, Gentile F, Jneid H, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143(5):e72-e227.

doi pubmed - Blanke P, Weir-McCall JR, Achenbach S, Delgado V, Hausleiter J, Jilaihawi H, Marwan M, et al. Computed tomography imaging in the context of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) / transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR): an expert consensus document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2019;13(1):1-20.

doi pubmed - Seto AH, Estep JD, Tayal R, Tsai S, Messenger JC, Alraies MC, Schneider DB, et al. SCAI position statement on best practices for percutaneous axillary arterial access and training. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2022;1(3):100041.

doi pubmed - Bavaria JE, Tommaso CL, Brindis RG, Carroll JD, Deeb GM, Feldman TE, Gleason TG, et al. 2018 AATS/ACC/SCAI/STS expert consensus systems of care document: operator and institutional recommendations and requirements for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a joint report of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and The Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107(2):650-684.

doi pubmed - Abusnina W, Machanahalli Balakrishna A, Ismayl M, Latif A, Reda Mostafa M, Al-Abdouh A, Junaid Ahsan M, et al. Comparison of Transfemoral versus Transsubclavian/Transaxillary access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2022;43:101156.

doi pubmed - Faroux L, Junquera L, Mohammadi S, Del Val D, Muntane-Carol G, Alperi A, Kalavrouziotis D, et al. Femoral versus nonfemoral subclavian/carotid arterial access route for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(19):e017460.

doi pubmed - Hayashida K, Lefevre T, Chevalier B, Hovasse T, Romano M, Garot P, Mylotte D, et al. Transfemoral aortic valve implantation new criteria to predict vascular complications. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(8):851-858.

doi pubmed - Chakos A, Wilson-Smith A, Arora S, Nguyen TC, Dhoble A, Tarantini G, Thielmann M, et al. Long term outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI): a systematic review of 5-year survival and beyond. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;6(5):432-443.

doi pubmed - Makkar RR, Thourani VH, Mack MJ, Kodali SK, Kapadia S, Webb JG, Yoon SH, et al. Five-year outcomes of transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(9):799-809.

doi pubmed - Allen KB, Chhatriwalla AK, Cohen DJ, et al. Transcarotid versus transapical and transaortic access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a propensity-score analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;114:222-232.

- Price J, Bob-Manuel T, Tafur J, Joury A, Aymond J, Duran A, Almusawi H, et al. Transaxillary TAVR leads to shorter ventilator duration and hospital length of stay compared to transapical TAVR. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2021;46(3):100624.

doi pubmed - Kaneko T, Hirji S, Pelletier M, et al. Real world outcomes of alternative access TAVR: insights from the TVT Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81:2257-2269.

- Barbanti M, Capranzano P, Ohno Y, et al. Optimizing patient discharge management after transfemoral TAVI: the multicentre European FAST-TAVI trial. EuroIntervention. 2018;14(15):1639-1647.

doi - Durand E, Cayla GL, Muir DF, et al. FAST-TAVI II: A training program reduces length of stay after transfemoral TAVI. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:ehae081

- Sohal S, Mehta H, Kurpad K, Mathai SV, Tayal R, Visveswaran GK, Wasty N, et al. Declining trend of transapical access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients with aortic stenosis. J Interv Cardiol. 2022;2022:5688026.

doi pubmed - Di Mario C, Goodwin M, Ristalli F, Ravani M, Meucci F, Stolcova M, Sardella G, et al. A prospective registry of intravascular lithotripsy-enabled vascular access for transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(5):502-504.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cardiology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.