| Cardiology Research, ISSN 1923-2829 print, 1923-2837 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cardiol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 16, Number 6, December 2025, pages 479-488

Epidemiological Trends of Heart Failure Subtypes, Characteristics, and Outcomes Within Inpatient Hospitalizations

Kayhon Rabbania, f, g , Cloie June Chiongb, f, Roy Mendozac, Pavneet Kaurc, Gail Mad, Liting Yangc, Alan Millere, David Loc, Shaokui Gec

aDepartment of Medicine, University of California, Irvine, Orange, CA, USA

bDepartment of Family Medicine, University of California, Irvine, Orange, CA, USA

cDepartment of Undergraduate Medical Education, Riverside School of Medicine, University of California, Riverside, CA, USA

dDepartment of Undergraduate Medical Education, Cebu Institute of Medicine, Cebu, Philippines

eDivision of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of Florida Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL, USA

fThese authors contributed equally to the article.

gCorresponding Author: Kayhon Rabbani, Department of Medicine, University of California, Irvine, Orange, CA, USA

Manuscript submitted July 19, 2025, accepted November 1, 2025, published online December 20, 2025

Short title: Epidemiology of Heart Failure Subtypes

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cr2118

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: This secondary analysis of a cross-sectional observational study aimed to evaluate the impact of heart failure (HF) classification on inpatient outcomes and demographic associations.

Methods: Data from the 2019 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) included 259,025 patients older than 18 years with a primary International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis of HF.

Results: Weighted results for this study showed that HF subtypes were stratified as diastolic (35.63%, n = 92,300), systolic (30.09%, n = 77,931), combined systolic-diastolic (18.74%, n = 48,529), other (11.81%, n = 30,593), end-stage (1.56%, n = 4,030), right (1.18%, n = 3,063), and biventricular (1.00%, n = 2,579). Acuity was categorized as acute on chronic HF (72.68%, n = 188,106), acute HF (10.79%, n = 27,948), chronic HF (1.84%, n = 4,778), and indeterminate (15%, n = 38,193). Demographically, older adults (≥ 75 years), African Americans, and males were found to be more frequently admitted, with age being the most significant factor. Younger patients (< 75 years) were more often diagnosed with non-diastolic HF, while minority groups had higher incidences of systolic and combined HF. Females were more likely to have diastolic HF compared to males. Right, biventricular, and end-stage HF were associated with increased inpatient costs, longer hospital stays, and higher mortality rates. Detailed HF classification reveals significant variations in inpatient outcomes and demographic associations.

Conclusions: Advanced HF subtypes incur higher costs, longer hospital stays, and increased mortality, underscoring the need for improved classification and earlier intervention across diverse populations. Further research is needed to refine HF diagnosis and coding to better understand and manage these conditions.

Keywords: Heart failure; Demographics; Patient acuity; Retrospective study

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Heart failure (HF) is one of the most challenging global threats to public health, particularly in the aging population [1]. In the United States, about 6 million people live with HF, with one in four individuals being likely to develop HF during their lifetime [2]. HF patients constitute over 1 million hospitalizations annually, which increased by approximately 20% from 2008 to 2018 [3]. Patient mortality, quality of life, and hospital outcomes have improved due to advances in medical and device therapies. In light of such advances, both prevalence and hospitalization of HF are still rising, in part because of the aging population and the extended life of HF patients. Therefore, HF remains a significant challenge in public health, medical science, and clinical practice [3, 4].

HF is a complex syndrome of various underlying functional mechanisms and structural differences. The classification of types of function and structure as well as clinical presentations of acuity, defined as acute HF, chronic HF, or acute on chronic HF, play critical roles for clinical decision making and strategic treatment plans, particularly for provisional personalized medicine [5]. Review of the literature shows that one in six patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) develop worsening HF within 18 months of HF diagnosis and have a high risk for 2-year mortality and recurrent HF hospitalizations [6]. Acute HFrEF was more common in Black and White men in comparison to their female counterparts, while acute HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) was most common in White women compared to White/Black men and Black women [7, 8]. Although patterns associated with demographic characteristics have been identified, there are few studies demonstrating the impact and cost burden of stratified HF according to type and acuity. While various epidemiological studies reviewing HFrEF and HFpEF characteristics and outcomes have been conducted throughout the United States and other countries, these studies did not analyze less common subtypes such as right, biventricular, and end-stage HF, nor was acuity mentioned as an additional influence on outcomes [9-11]. Examining HF by type and acuity can address the specific impact and clinical manifestations of each etiology, minimize expenses, and improve long-term outcomes for patients. Furthermore, assessing the characteristics of HF patients and their prognoses following discharge can provide insight into future risk stratification, therapeutic management, and clinical trial designs for better management. With the goal of providing evidence about the national trends of HF subtypes and acuity, this study used the 2019 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) to demonstrate the national rates of HF discriminated by subtypes and acuity that were further characterized by demographics.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Data source

The 2019 NIS was ordered from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), which was sponsored by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality [12, 13]. The NIS design has a complex sampling scheme for capturing approximately 20% of inpatient data and representing over 7 million hospitalizations annually. This dataset includes deidentified individuals with a primary diagnosis (i.e., admission diagnosis) and secondary diagnoses, adhering to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM). To standardize and compare the NIS based national trends of HF in demographics, the national estimation of the civilian population in 2019 were extracted from the US Census Bureau [14]. The Institutional Review Board approval was not applicable/required as data from NIS are deidentified. This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible institution as well as with the Helsinki Declaration.

Measures

This study analyzed a subsample of NIS study inpatients diagnosed with HF based on the primary diagnosis codes of I50, I13.2, I11.0, and I13.0. The latter three codes adhere to the “Code First” rule, prioritizing the underlying chronic disorder or cause, followed by its manifestation. Detailed coding for subtypes and acuity can be found here (Supplementary Material 1, cr.elmerpub.com).

In terms of race/ethnicity of inpatients in the NIS, race/ethnicity was defined as African American (AA), Asian-American and Pacific Islander (API), Hispanic, White, or other racial/ethnic identity. “Sex” was recorded as a binary variable. Age in years at admission was recoded into four categories: 18 - 34, 35 - 54, 55 - 74, and ≥ 75. Inpatients younger than 18 years old were excluded, as HF is a rare occurrence for adolescents.

Data analysis

Analyses for his nationally representative dataset were estimated by the sample-weighted method, for which NIS discharge weight was used as the sample weight, the national division of hospitals was the stratificational factor, and hospital IDs were the clustering variable. The association between HF hospitalization and demographics was analyzed using the Rao-Scott Chi-square test.

A Poisson regression model, incorporating a quasi-Poisson link, was formulated to assess the incident rate ratio (IRR) of HF hospitalizations. This model was standardized according to the national population. The counts of HF inpatient encounters within each demographic group served as the dependent variables. Consequently, IRR and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were presented as relative risks for demographically defined groups that were hospitalized primarily due to HF.

To evaluate the risk of specific subtype diagnosis for admitted HF inpatients, a survey-based logistic regression model was established, employing hospital division as the stratification factor and hospital ID as the clustering element. In this model, HF subtypes, identified by ICD-10 codes, were the dependent outcomes, while demographics were the independent variables. Diastolic HF was chosen as the reference subtype.

To further discern these HF subtypes by levels of acuity, another survey-based logistic regression model was constructed. In addition to demographics, HF subtypes served as independent variables. The chronic classification was used as the reference level of acuity. Risks were conveyed as IRRs along with their 95% CIs for various independent variables.

| Results | ▴Top |

A total of 6,043,654 hospitalized patients were identified in the NIS 2019 database, of whom 259,025 had a primary diagnosis of HF on admission. The weighted national estimate of patients with the primary hospital admission diagnosis of HF was 1.30 million, representing 4.30% of all inpatient stays. Such hospitalizations had strong demographic characterizations (Table 1). Among HF inpatients in our unweighted sample, there were 165,566 Whites (63.9%), 55,031 AAs (21.2%), 20,972 Hispanics (8.1%), 5,664 Asian Pacific Islanders (2.2%), and 11,792 patients identifying as other races/ethnicity (other) (4.6%), respectively; including 135,987 males (52.5%) and 123,031 females (47.5%). The distributions by age group were 18 - 34 years (n = 3,375, 1.3%), 35 - 54 years (n = 30,187, 11.7%), 55 - 74 (n = 104,306, 40.3%), and 75 years and older (n = 121,157, 46.8%), respectively. AA inpatients had the highest HF hospitalization rate of 6.1%, followed by 4.2% for Whites, 3.4% for API and others, and 3.2% for Hispanics. The rates for male and female inpatient HF hospitalizations were 5.2% and 3.6%, respectively. Age displayed a significant gradient in HF inpatients, from 0.3% in the young adult (18 - 43 years old) group to 8.0% in seniors ≥ 75, a nearly 27-fold increase. Consequently, age had a greater difference in the HF diagnosis rate compared to race or sex among inpatients.

Click to view | Table 1. Comparisons Between Hospitalizations With and Without a Primary Diagnosis of HF |

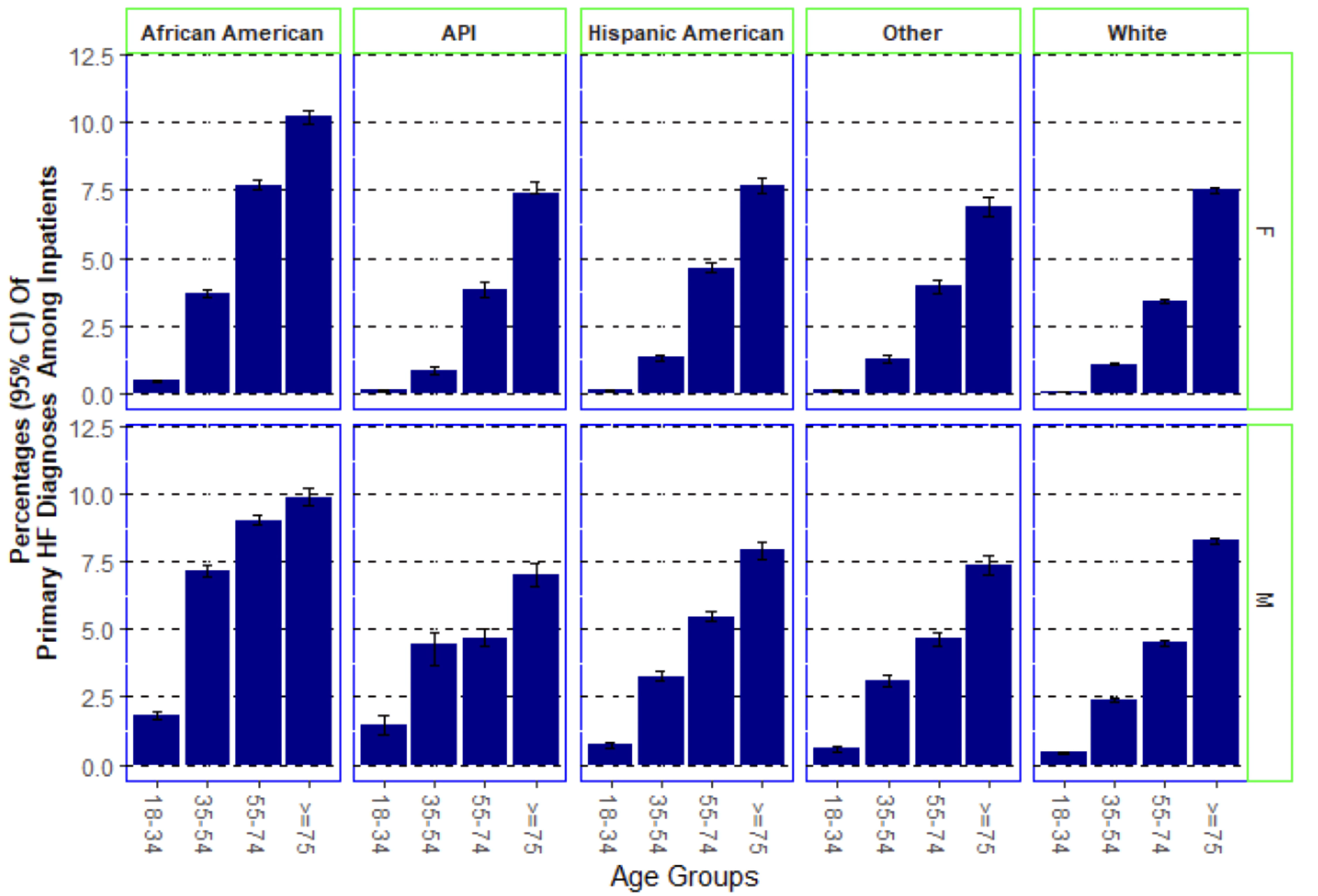

Furthermore, diagnosis rates of different age groups were stratified by sex across race (Fig. 1). HF diagnosis rates consistently increased with age, and the rates changed uniquely by sex in all five racial groups. In the age group of individuals aged 75 and older, the rates of HF diagnosis were comparable between males and females across different racial groups, albeit with some variance. Notably, AA males and females exhibited slightly higher HF diagnosis rates of 9.9% (n = 5,029) and 10.2% (n = 8,374), respectively. In contrast, Whites had diagnosis rates of 8.3% for males (n = 43,048) and 7.5% for females (n = 49,289). Hispanic males and females were diagnosed at rates of 7.9% (n = 3,273) and 7.7% (n = 4,376), respectively. Asian Pacific Islanders showed rates of 7.0% for males (n = 1,203) and 7.4% for females (n = 1,608). Additionally, patients of other racial/ethnic identity reported rates of 7.3% for males (n = 2,254) and 6.9% for females (n = 2,699). These findings underscore an elevated HF diagnosis prevalence in AAs compared to other races within this elderly cohort. It was noted that all males in the five race groups were diagnosed with HF at earlier ages compared to their female peers. In particular, HF diagnoses in young AA and API males in the 18 - 34 age group were more prevalent compared to their female peers. AA males had HF diagnosis rates of 1.8% (n = 978), 7.2% (n = 7,657), and 9.0% (n = 14,747) at the ages of 18 - 34, 35 - 54, and 55 - 74, while AA females in these three age groups had rates of 0.5% (n = 699), 3.7% (n = 4,799), and 7.7% (n = 12,746), respectively. API male inpatients in these age groups had HF diagnosis rates of 1.5% (n = 83), 4.4% (n = 533), and 4.7% (n = 1,147), while their API female peers had rates of 0.1% (n = 36), 0.8% (n = 205), and 3.8% (n = 849), respectively.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Percentages of heart failure (HF) hospitalizations across age group, race/ethnicity, and sex. This sample-weighted national estimation illustrates the percentages of patients hospitalized with a primary diagnosis of heart failure stratified by age groups, race/ethnicity, and sex. Error bars and value in parentheses represent 95% confidence intervals (CIs). HF: heart failure; API: Asian-American and Pacific Islander. |

Demographic differences were evident in the civilian population’s IRRs (Table 2). Compared to White patients, those from AA and other racial/ethnic backgrounds had higher hospital admission rates for primary HF diagnosis (IRR = 2.49 and 3.48 with 95% CIs of 2.06 - 2.98 and 2.39 - 4.87, respectively). In contrast, APIs had half the admission rate for primary HF diagnosis (IRR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.29 - 0.80). Males had a 38% higher admission rate compared to females (IRR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.19 - 1.59). Young adults (18 - 34 years) had a lower likelihood of HF admission compared to seniors aged 75 and above. The risk of hospitalization for the primary HF diagnosis was considerably lower in the 35 - 54 age group (IRR = 0.06, 95% CI: 0.05 - 0.08). Early seniors (55 - 74 years) had 25% of the hospitalization risk for HF compared to those 75 and above (IRR = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.21 - 0.29).

Click to view | Table 2. Risk Assessment of HF Encounters for the General Population Estimated by the 2019 US Census |

Table 3 depicts national trends for HF subtypes and their acuity. Diastolic and systolic HF accounted for 35.63% and 30.09% of inpatients, respectively, followed by combined systolic-diastolic HF (18.74%). Right, end-stage, and biventricular HF each accounted for less than 2% of HF cases. Notably, 30,593 (11.81%) HF inpatients were not specified for subtype. Regarding acuity, 72.68% of inpatients were admitted with acute on chronic HF, 10.79% with acute HF, and 1.84% with chronic HF. Additionally, 14.69% of inpatients were unspecified in terms of acuity. This category also included all those unspecified by subtype. A clear trend in acuity was observed across the HF subtypes (Supplementary Material 2, cr.elmerpub.com). The two most common subtypes, diastolic and systolic, both had over 80% diagnosed as acute on chronic, 14% as acute, and a mere 1% as unspecified. The combined type had 82% as acute on chronic, 7% as acute, and 9% unspecified. Over 10% of right, end-stage, and biventricular HF cases remained unspecified for acuity.

Click to view | Table 3. National Estimation of HF Inpatients Classified by Type and Acuity With Corresponding Hospital Outcomes |

Hospital outcomes were also significantly different for subtypes and acuity. On average, the lengths of stay in hospitals ranged from 5.16 days for systolic HF to 10.77 days for end-stage HF. Their total charges changed from $47,840 for diastolic HF to $174,290 for end-stage HF patients. Hospital mortality varied between 1.89% of diastolic HF patients and 10.33% of end-stage HF patients. Comparing the hospital outcomes for acuity, it was noted that acute HF patients stayed the shortest duration, were charged the least, and had the fewest in-hospital deaths. The undefined or unspecified HF inpatients had the worst outcomes.

HF inpatient subtypes showed strong associations with demographics (Tables 4, 5). Compared to Whites, ethnic minorities had higher odds of having systolic HF and combined systolic-diastolic HF, with odds ratios (ORs) ranging from 1.14 to 1.59, less than a two-fold difference. However, Hispanic inpatients were less likely to have right HF (OR = 0.86). AA patients were 50% more likely to be diagnosed with biventricular HF (OR = 1.50), but this trend was not observed in other ethnicities. AAs (OR = 1.71), Hispanics (OR = 1.30), and other ethnicities (OR = 1.26) showed a higher likelihood of being diagnosed with end-stage HF. Ethnic minorities had a higher likelihood of unspecified HF, with ORs between 1.76 and 2.45. Female inpatients had lower odds of all of HF diagnoses rather than diastolic HF, compared to male inpatients. Compared to the oldest age group (≥ 75 years), younger age groups had higher odds for all other HF types relative to diastolic HF, including right HF (OR = 8.40), end-stage (OR = 7.56), biventricular (OR = 5.68), and unspecified HF (OR = 5.76), followed by systolic HF (OR = 4.43) and combined HF (OR = 3.07). This suggests that younger patients were more often admitted with more advanced HF types than their older counterparts. These differences of risk strength implies that age played a greater role than race and sex in profiling HF subtypes. Acuity risk varied by demographic and subtype. Compared to Whites, AAs, Hispanics, and individuals who identified as other races/ethnicity were less likely to be diagnosed with acute HF, with ORs of 0.67, 0.76, and 0.79, respectively. Hispanics and those of other racial/ethnic background were less likely to be diagnosed with acute on chronic HF (ORs of 0.85 and 0.81). Minority groups were also more likely to have unspecified acuity, with ORs between 1.22 and 2.02. Female inpatients were more likely to have acute, acute on chronic, and unspecified acuity than males. Younger (18 - 34) patients had higher odds of acute or unspecified acuity. Compared to diastolic HF, systolic HF had a slightly higher risk of being acute but a lower risk of unspecified acuity. Combined systolic-diastolic HF was less likely to be acute than acute on chronic and unspecified. Right, end-stage, and biventricular HF were less likely to be acute or acute on chronic but were more often unspecified for acuity.

Click to view | Table 4. Relative Risk Assessment for the Clinical Classification of HF Inpatients Defined by ICD-10 Codes |

Click to view | Table 5. Relative Risk Assessment for Acuity of HF Diagnoses Using Chronic HF as Control |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Using the 2019 NIS, this study demonstrated that a weighted estimate of 1.3 million inpatients was admitted to hospitals with a primary diagnosis of HF, contributing to an overall 4.20% in the national inpatient estimation. The rates of HF hospitalization among demographic-specific subgroups revealed significant disparities: AAs, males, and individuals ≥ 75 years were disproportionately more likely to be hospitalized with a primary diagnosis of HF, compared to their counterparts. This study’s comparison with NIS data from 2007 to 2017 showed that national hospitalizations for primary HF diagnoses continued to increase, rising from 1.21 million in 2017 [15]. The admission rate for a primary HF diagnosis, standardized to the national civilian population of 2019, was about 500 per 100,000 people. This rate marks a return to the trend observed in 2010, after which a decrease had been noted [16].

An important concept of this study is utilizing the ICD-10 coding rules to describe national patterns in clinically classifying HF diagnoses by function, anatomical location, and acuity. This practice aims to promote accurate and comprehensive coding for emerging innovations in medicine, including precision and personalized medicine, automatic coding systems, and artificial intelligence (AI)-supported healthcare [17-19]. Using these detailed codes, we found that systolic HF (30.09%, n = 77,931), diastolic HF (35.63%, n = 92,300), and combined systolic-diastolic HF (18.74%, n = 48,529) were predominant among HF inpatients. We also quantitatively illustrated how these HF diagnoses correlated with demographic factors. For instance, compared to White patients with primary diastolic HF, all three other ethnic and racial groups were more likely to receive a systolic HF diagnosis.

Moreover, this study expanded the concept of healthcare disparities to include the metric of undefined or inaccurate medical coding practices. Compared to White inpatients, those of AA, Hispanic, Asian American and Pacific Islander, and of other ethnic/racial backgrounds were more likely to have incomplete, inaccurate, or nonspecific codes, with ORs of 1.99, 2.45, 2.34, and 1.76, respectively. They also had higher chances of unspecified acuity, with ORs of 1.36, 1.73, 2.02, and 1.22, respectively.

Chronic and unspecified HF, along with advanced presentations of HF, demonstrated higher hospital costs, length of stay, and mortality. This is supported by other studies, which have shown that patients diagnosed with HF of an unknown subtype had high rates of mortality and resource utilization [20]. End-stage HF had the greatest cost, length of stay, and inpatient mortality compared to all other examined HF etiologies. Isolated left ventricular HFs (systolic HF, diastolic HF, combined systolic-diastolic HF) had the lowest inpatient mortalities, costs, and length of stay with the exception of undisclosed HF having a similar length of stay compared to the isolated left ventricular HFs.

Higher acuity was also found to decrease inpatient mortality and total cost, with length of stay remaining similar in acute HF and chronic HF patients. This is consistent with current literature, likely because patients with acute HF are likely younger, have less comorbidities, and have lower likelihood of prior cardiac events [21-23]. However, this study revealed that younger inpatients were more likely to have less common subtypes of HF, such as right, end-stage, and biventricular HF. Compared to inpatients aged 75 or older, those aged 18 - 34 were more likely to be admitted for right HF, biventricular HF, and end-stage HF. This calls for early intervention and management of HF risk factors in young adulthood, as well as further research to better understand the causal factors associated with such early and severe diagnoses.

Limitations

Our study’s constraints include our limited ability to explore clinical mechanisms and explanations, such as vital signs, medication use, and diagnostic tests of the studied HF etiologies due to the lack of detailed clinical information available on the HCUP database. This limitation prevents us from determining whether appropriate treatments were used that may have influenced demographic trends, hospital outcomes, and acuity. Our data are also limited in the regard that the HCUP database solely utilizes inpatient data; HF in hospitals is dominated by acute and acute on chronic HF, whereas HF overall, including outpatient cases, may be dominated by chronic HF. Future research should aim to shed light on how hospital outcomes, including cost, length of stay, and in-hospital mortality are shaped by clinical variables such as diagnostic tests and symptoms, in addition to demographic and socioeconomic factors. Accurately discerning HF trends while accounting for potential confounding variables will enable us to devise targeted, effective interventions for HF management and prevention, subsequently leading to a potential reduction in hospital expenditures.

Conclusions

The prevailing literature predominantly addresses HF as a singular diagnostic category. In contrast, our study delves into a more nuanced understanding, segmenting HF into seven distinct categories. We estimated the national representative trends of these seven types and their acuity presentation types and found that race displayed varied trends depending on the specific HF category. There is a pronounced increase in HF hospitalization risks by race, with AAs bearing the most significant burden in comparison to other racial/ethnic groups. Age also played an important role in profiling the subtypes and acuity in patients hospitalized with a primary diagnosis of HF. Young adults had higher risks of developing less common subtypes of HF - right, end-stage, biventricular HF - as well as acute HF presentations. Chronic and undefined acuity of HF had higher mortality rates, length of stay, and cost of care compared to more acute HF episodes. However, little research has been conducted on the differences between these etiologies and their prevalence, highlighting the importance of specific classification of HF acuity at diagnosis and further research regarding their outcomes.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. ICD 10 codes for HF diagnoses, subtypes, and acuity.

Suppl 2. Distributions of HF subtypes by acuity.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the University of California, Riverside School of Medicine Research Division for their support and cooperation throughout the research period.

Financial Disclosure

This study was supported by internal funding provided by the University of California, Riverside School of Medicine Research Division.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was not applicable/required for this study using deidentified data.

Author Contributions

Kayhon Rabbani: design, acquisition, interpretation, writing, editing. Cloie June Chiong: conception, design, acquisition, interpretation, writing, editing. Roy Mendoza: writing, editing. Pavneet Kaur: writing. Gail Ma: writing. Liting Yang: writing. Alan Miller: editing. David Lo: editing, funding acquisition. Shaokui Ge: acquisition, analysis, interpretation, writing, editing.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Shahim B, Kapelios CJ, Savarese G, Lund LH. Global public health burden of heart failure: an updated review. Card Fail Rev. 2023;9:e11.

doi pubmed - Bozkurt B, Ahmad T, Alexander KM, Baker WL, Bosak K, Breathett K, Fonarow GC, et al. Heart failure epidemiology and outcomes statistics: a report of the heart failure society of America. J Card Fail. 2023;29(10):1412-1451.

doi pubmed - Clark KAA, Reinhardt SW, Chouairi F, Miller PE, Kay B, Fuery M, Guha A, et al. Trends in heart failure hospitalizations in the US from 2008 to 2018. J Card Fail. 2022;28(2):171-180.

doi pubmed - Sidney S, Go AS, Jaffe MG, Solomon MD, Ambrosy AP, Rana JS. Association between aging of the US population and heart disease mortality from 2011 to 2017. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(12):1280-1286.

doi pubmed - Banerjee A, Dashtban A, Chen S, Pasea L, Thygesen JH, Fatemifar G, Tyl B, et al. Identifying subtypes of heart failure from three electronic health record sources with machine learning: an external, prognostic, and genetic validation study. Lancet Digit Health. 2023;5(6):e370-e379.

doi pubmed - Jain V, Minhas AMK, Khan SU, Greene SJ, Pandey A, Van Spall HGC, Fonarow GC, et al. Trends in HF hospitalizations among young adults in the United States from 2004 to 2018. JACC Heart Fail. 2022;10(5):350-362.

doi pubmed - Chang PP, Wruck LM, Shahar E, Rossi JS, Loehr LR, Russell SD, Agarwal SK, et al. Trends in hospitalizations and survival of acute decompensated heart failure in four US communities (2005-2014): ARIC Study Community Surveillance. Circulation. 2018;138(1):12-24.

doi pubmed - Dunlay SM, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Epidemiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14(10):591-602.

doi pubmed - Escobar C, Palacios B, Varela L, Gutierrez M, Duong M, Chen H, Justo N, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, management and outcomes of patients with heart failure with preserved, mildly reduced, and reduced ejection fraction in Spain. J Clin Med. 2022;11(17):5199.

doi pubmed - Goyal P, Almarzooq ZI, Horn EM, Karas MG, Sobol I, Swaminathan RV, Feldman DN, et al. Characteristics of hospitalizations for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Med. 2016;129(6):635.e615-626.

doi pubmed - Kitai T, Miyakoshi C, Morimoto T, Yaku H, Murai R, Kaji S, Furukawa Y, et al. Mode of death among Japanese adults with heart failure with preserved, midrange, and reduced ejection fraction. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e204296.

doi pubmed - 2019 Introduction to the NIS. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). September 2021. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NIS_Introduction_2019.jsp.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Content last reviewed July 2024. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/index.html.

- US Census Bureau. 2019. 2019 National and State Population Estimates. Census.gov. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2019/national-state-estimates.html.

- Agarwal MA, Fonarow GC, Ziaeian B. National trends in heart failure hospitalizations and readmissions from 2010 to 2017. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(8):952-956.

doi pubmed - Jackson SL, Tong X, King RJ, Loustalot F, Hong Y, Ritchey MD. National burden of heart failure events in the United States, 2006 to 2014. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(12):e004873.

doi pubmed - Dash S, Shakyawar SK, Sharma M, Kaushik S.. Big data in healthcare: management, analysis and future prospects. J Big Data. 2019;6:54.

doi - Dong H, Falis M, Whiteley W, Alex B, Matterson J, Ji S, Chen J, et al. Automated clinical coding: what, why, and where we are? NPJ Digit Med. 2022;5(1):159.

doi pubmed - Blundell J. Health information and the importance of clinical coding. Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine. 2023;24(2):96-98

doi - Linden S, Gollop ND, Farmer R. Resource utilisation and outcomes of people with heart failure in England: a descriptive analysis of linked primary and secondary care data - the PULSE study. Open Heart. 2023;10(2):e002467.

doi pubmed - Greene SJ, Hernandez AF, Dunning A, Ambrosy AP, Armstrong PW, Butler J, Cerbin LP, et al. Hospitalization for recently diagnosed versus worsening chronic heart failure: from the ASCEND-HF trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(25):3029-3039.

doi pubmed - Lassus JP, Siirila-Waris K, Nieminen MS, Tolonen J, Tarvasmaki T, Peuhkurinen K, Melin J, et al. Long-term survival after hospitalization for acute heart failure—differences in prognosis of acutely decompensated chronic and new-onset acute heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(1):458-462.

doi pubmed - Younis A, Mulla W, Goldkorn R, Klempfner R, Peled Y, Arad M, Freimark D, et al. Differences in mortality of new-onset (De-Novo) acute heart failure versus acute decompensated chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124(4):554-559.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cardiology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.