| Cardiology Research, ISSN 1923-2829 print, 1923-2837 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cardiol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 16, Number 6, December 2025, pages 499-506

Impact of Patent Foramen Ovale on In-Hospital Outcomes in Acute Pulmonary Embolism

Ahmad Jabria, Sant Kumarb, Mohamed Zghouzic, Mohamed Farhan Nasserd, Anand Maligireddye, Raef Fadelc, Brian O’Neillc, Pedro Villablancac, Pedro Engel-Gonzalezc, Tiberio Frisolic, Herbert D. Aronowc, f, Mohammad Alqarqazc, Gennaro Giustinoc, Herman Kadoa, Amr Abbasa, Vikas Aggarwalc, g

aDepartment of Cardiovascular Medicine, Corewell Health William Beaumont University Hospital, Royal Oak, MI, USA

bDepartment of Cardiology, Creighton University School of Medicine, Phoenix, AZ, USA

cDivision of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI, USA

dDepartment of Internal Medicine, The Wright Center for Graduate Medical Education, Scranton, PA, USA

eDepartment of Cardiovascular Medicine, Heart and Vascular Center, Case Western Reserve University/Metrohealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH, USA

fDepartment of Cardiovascular Medicine, Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, East Lansing, MI, USA

gCorresponding Author: Vikas Aggarwal, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI, USA

Manuscript submitted August 11, 2025, accepted October 31, 2025, published online December 20, 2025

Short title: Pulmonary Embolism and Patent Foramen Ovale

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cr2130

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Patent foramen ovale (PFO) may complicate acute pulmonary embolism (PE) by enabling paradoxical embolism, but its clinical impact remains unclear. We evaluated the characteristics, management, and outcomes of patients hospitalized with PE with or without PFO.

Methods: Using the National Inpatient Sample database, adult patients admitted with acute PE between 2016 and 2020 were identified via ICD-10 codes. Patients were grouped based on whether they had concomitant PFO. Clinical characteristics, advanced therapies, and in-hospital outcomes were compared between patients with and without PFO. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were adjusted for demographics and comorbidities, with outcomes reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

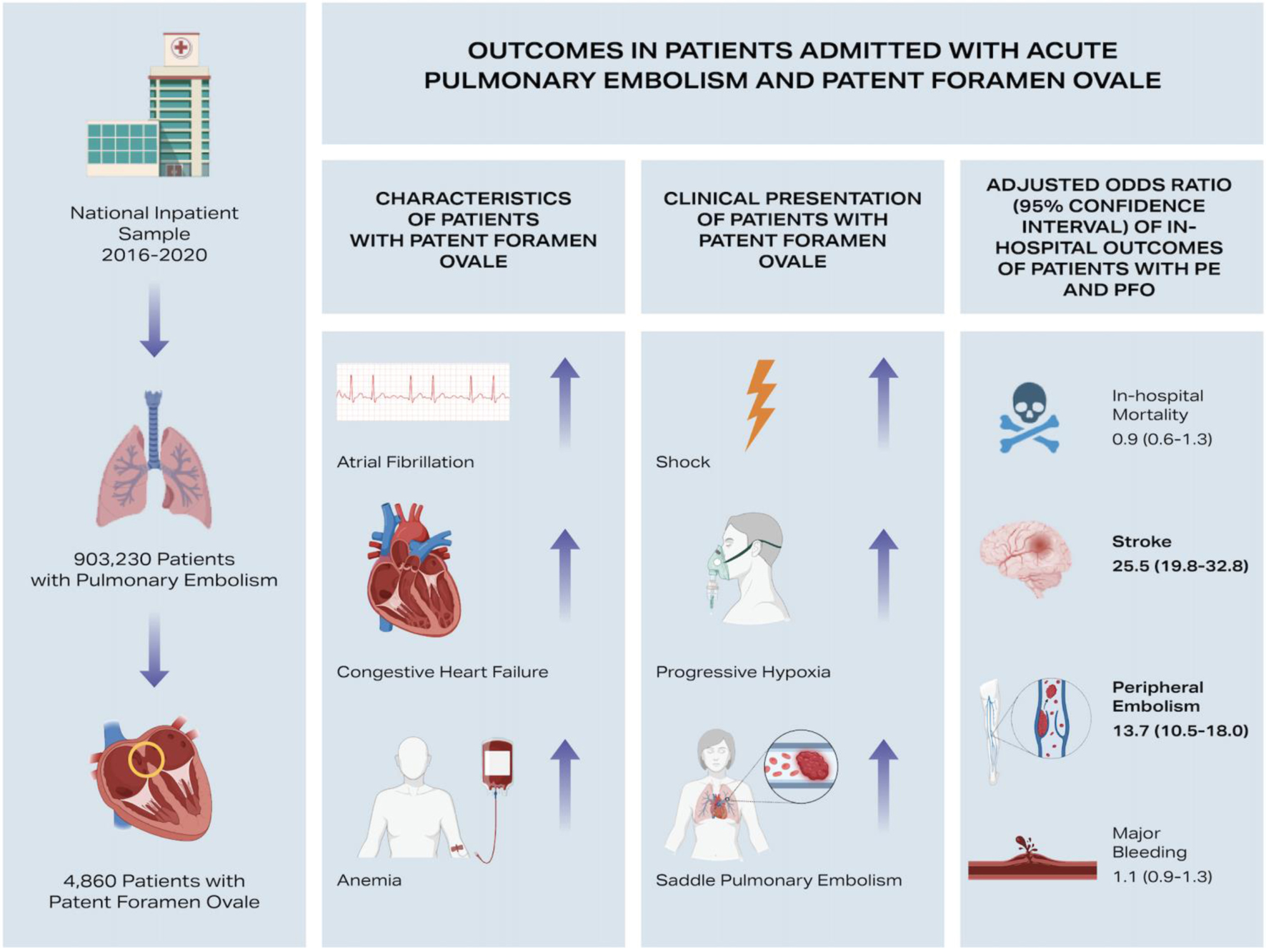

Results: We identified 903,230 adult patients hospitalized with acute PE, among whom 4,860 (0.54%) had a PFO. Patients with concomitant PE and PFO were younger (59.4 ± 15.9 vs. 63 ± 16.5 years, P < 0.001) and presented with more severe clinical features, including higher rates of saddle PE (17.7% vs. 9%, P < 0.001) and cor pulmonale (17.9% vs. 8.3%, P < 0.001). They required significantly more frequent interventions, such as catheter-directed thrombolysis (7.4% vs. 3.8%, P < 0.001). After multivariable adjustment, PFO presence was associated with significantly increased odds of stroke (aOR 25.5, 95% CI 19.8 - 32.8; P < 0.001) and peripheral embolism (aOR 13.7, 95% CI 10.5 - 18.0; P < 0.001) but not increased in-hospital mortality (aOR 0.9, 95% CI 0.6 - 1.3; P = 0.702).

Conclusion: In this nationwide study, PFO in patients with acute PE was linked to greater clinical severity and more frequent advanced interventions. Prospective studies are needed to define optimal screening strategies.

Keywords: Pulmonary embolism; Patent foramen ovale; Stroke; Paradoxical embolism

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a significant cardiovascular condition associated with high morbidity, mortality, and substantial healthcare utilization [1, 2]. It represents the third most common cause of cardiovascular-related deaths, affecting hundreds of thousands of patients annually in the United States [1]. In addition to acute complications such as hemodynamic instability and death, PE can lead to long-term consequences, including chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) and recurrent thromboembolic events [3, 4]. Notably, a patent foramen ovale (PFO) - a persistent, congenital opening between the right and left atria - can complicate the clinical course of PE through the phenomenon of paradoxical embolism [5]. The elevated right-sided heart pressures during acute PE may facilitate right-to-left shunting through a PFO, resulting in paradoxical arterial emboli, including ischemic strokes, systemic embolization, and worsened hypoxemia [6].

Several retrospective, prospective, and meta-analytic studies have highlighted the clinical implications of a PFO in patients presenting with acute PE [7-10]. The presence of a PFO has consistently been associated with a significantly increased risk of stroke, systemic embolization, and higher short-term mortality. However, the literature remains heterogeneous, particularly regarding the actual prevalence of PFO in large, nationally representative populations and detailed characterization of clinical features, management strategies, and associated outcomes in patients admitted with PE and concomitant PFO. Importantly, existing large-scale studies predominantly focus on PFO prevalence in stroke patients [10, 11], therapeutic interventions for PE alone [12, 13], and therapeutic interventions for PFO alone [14], and thus fail to adequately address the intersection between PE and PFO at a population level.

To address this gap in the literature, we utilized the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) to perform a comprehensive analysis of adult patients admitted with acute PE. Specifically, we aimed to assess the incidence and clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed with PE who also had documented PFO. Additionally, our study evaluates contemporary management strategies utilized in this unique patient population, including thrombolytic therapy. Given the significant clinical implications of concomitant PE and PFO, clarifying the epidemiology and treatment patterns at the national level can provide valuable insights for clinicians and policymakers. It is, however, important to acknowledge that the lack of systematic screening inherently limits the identification of PFOs in administrative datasets.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Data source

We identified patients from the 2016 to 2020 NIS. The NIS, part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), which is managed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, is a collaborative project involving federal, state, and private sector entities. Each year, the NIS compiles administrative claims data from approximately 7 million hospitalizations from 47 states and the District of Columbia, covering 97% of the US population. The NIS’s annual data aggregation enables longitudinal analysis of disease patterns using trend weights developed by HCUP [15]. This study involved the analysis of de-identified data and was exempt from the institutional review board’s approval. This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible institution on human subjects as well as with the Helsinki Declaration.

Study population

ICD-10 codes were used to identify hospital encounters of patients admitted with acute PE. Patients were stratified according to whether a concomitant diagnosis of PFO was present. A list of ICD-10 diagnosis and procedure codes for identifying the study population is provided in Supplementary Material 1 (cr.elmerpub.com). Baseline patient-level characteristics included demographics (age, sex, primary expected payer, median household income for patient’s zip code) and relevant comorbidities (smoking, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure (CHF), renal failure, obesity, coagulopathy, anemia, and metastatic cancer). Hospital-level characteristics included bed size. We identified comorbidities using the ICD-10 codes as shown in Supplementary Material 2 (cr.elmerpub.com).

PE management therapies were defined as systemic thrombolysis (ST), catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT), catheter-directed embolectomy (CDE), and surgical embolectomy (SE). ICD-10 codes used to identify the comorbidities and advanced PE therapies are included in Supplementary Material 3 (cr.elmerpub.com).

Outcomes

The outcomes assessed included all-cause mortality, stroke, peripheral embolism, and bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, hematuria, respiratory bleeding, and the need for blood transfusion. The ICD-10 codes used to define these outcomes are listed in Supplementary Material 4 (cr.elmerpub.com).

Statistical analysis

Weighted values of patient-level observations were used to produce nationally representative estimates of the entire US population of hospitalized patients. Continuous variables were expressed as weighted mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were compared using the unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Chi-square or Fisher exact testing was used to compare categorical variables as appropriate. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression was employed to estimate the odds of in-hospital outcomes. Regression models were adjusted for demographics and all comorbidities listed in Supplementary Material 5 (cr.elmerpub.com). Results of regression models were reported using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Stata version 18 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) was utilized for all statistical analyses.

| Results | ▴Top |

Overall, we identified 903,230 patients admitted with acute PE. As shown in Supplementary Material 5 (cr.elmerpub.com), patients admitted with PE and PFO were significantly younger (59.4 ± 15.9 years vs. 63 ± 16.5 years; P < 0.001) compared to those with PE alone, although the proportion of females was similar between groups (50.7% vs. 51.8%, P = 0.510). Statistically significant differences were also noted in several comorbidities: patients with PE and PFO had higher rates of atrial fibrillation (18.7% vs. 16.2%, P = 0.030), CHF (28.8% vs. 18.5%, P < 0.001), and anemia (9% vs. 6.4%, P = 0.001). Conversely, the prevalence of renal failure (11% vs. 13.3%, P = 0.035) and metastatic cancer (4.5% vs. 7.8%, P < 0.001) was significantly lower in patients with PE and concomitant PFO.

Patients admitted with PE and PFO presented with significantly sicker clinical profiles compared to those with PE alone. Specifically, patients with PFO had substantially higher rates of saddle PE (17.7% vs. 9%, P < 0.001), cor pulmonale (17.9% vs. 8.3%, P < 0.001), progressive hypoxia (14.4% vs. 5.8%, P < 0.001), and requirement for pressors (3.5% vs. 0.8%, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Clinical Presentation in PE Patients With and Without PFO |

Similarly, patients with concomitant PE and PFO required significantly higher utilization of advanced therapeutic interventions compared to those with PE alone (Table 2). Specifically, the use of ST (3.7% vs. 2.5%, P = 0.010), SE (7.5% vs. 0.2%, P < 0.001), CDT (7.4% vs. 3.8%, P < 0.001), and CDE (4.3% vs. 1.3%, P < 0.001) were all significantly greater in the PE with PFO group, emphasizing the increased severity and complexity of management in these patients.

Click to view | Table 2. Advanced Therapies in PE Patients With and Without PFO |

After adjusting for demographics and comorbidities, patients with concomitant PE and PFO demonstrated significantly increased odds of stroke (adjusted OR 25.5, 95% CI 19.8 - 32.8, P < 0.001) and peripheral embolism (adjusted OR 13.7, 95% CI 10.5 - 18.0, P < 0.001) compared to patients with PE alone. There was no significant difference in adjusted odds for in-hospital mortality (adjusted OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.6 - 1.3, P = 0.702) (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 3. In-Hospital Outcomes in PE Patients With and Without PFO |

Patients with PE and concomitant PFO had significantly greater healthcare resource utilization, with higher adjusted hospitalization costs ($30,723 ± $57,305 vs. $12,008 ± $15,116, P < 0.001) compared to those without PFO (Table 4).

Click to view | Table 4. Resources Utilization |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In this large nationwide analysis of 903,230 patients hospitalized with acute PE, patients with concomitant PFO were significantly younger and exhibited distinct clinical characteristics, including higher rates of atrial fibrillation and CHF. Patients with PE and PFO presented with notably more severe clinical manifestations, such as higher rates of cor pulmonale and increased requirement for pressors. Correspondingly, these patients required significantly greater use of advanced therapeutic interventions, including ST and CDT. After adjusting for demographics and comorbidities, patients with concomitant PE and PFO had significantly increased odds of stroke and peripheral embolism, though there was no significant difference in adjusted odds of in-hospital mortality (Fig. 1). The greater use of advanced therapeutic interventions and higher healthcare resource utilization observed in PFO carriers with PE are plausibly explained by the compounding effect of systemic embolic complications on top of the hemodynamic burden of acute PE.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Clinical characteristics, severity of presentation, and in-hospital outcomes of patients admitted with acute pulmonary embolism (PE) and concomitant patent foramen ovale (PFO). |

Konstantinides et al performed a retrospective analysis involving 139 patients admitted with acute PE, detecting PFO in 35% of cases and demonstrating increased mortality and systemic embolization in those with PFO [1]. While our study similarly identified significantly increased risks of stroke and peripheral embolism, we did not find significantly increased adjusted in-hospital mortality among PE patients with PFO, highlighting differences likely due to advancements in acute PE management over the past two decades. Le Moigne et al conducted a prospective cohort study involving 361 patients hospitalized with acute PE, systematically evaluated for PFO. The study reported a PFO prevalence of 13% and identified significantly higher stroke rates in PE patients with PFO compared to those without [9]. Similarly, Lucas et al conducted a meta-analysis of eight studies totaling 1,197 PE patients, reporting a pooled PFO prevalence of approximately 20-25% and a significantly elevated risk of stroke among those with PFO [7]. Our findings strongly align with these two, confirming increased stroke risk. Moreover, in our study, the degree of underdiagnosis was notable, with only 0.5% of patients coded as having a PFO, implying that roughly one in four patients in the comparison group likely harbored an undiagnosed PFO. As a result, the presence of these “blind passengers” in the non-PFO cohort would have diluted the differences in outcomes between groups. It follows that, if PFOs were more accurately identified, the adverse impact of PFO on embolic complications - particularly ischemic stroke - would likely have appeared even more pronounced.

Our study, however, identified a notably lower prevalence of PFO among patients with acute PE. This discrepancy may reflect real-world clinical practice captured by the NIS, where systematic evaluation for PFO is uncommon among patients admitted with PE. Indeed, data from large registries, such as the Registro Informatizado de la Enfermedad TromboEmbolica (RIETE) registry, have shown that most patients with acute PE do not routinely undergo dedicated screening for PFO, with only a minority receiving targeted echocardiographic evaluation [16]. Consequently, our observed lower prevalence of PFO may underscore the selective and often clinically driven approach to PFO assessment in routine clinical care, as opposed to systematic screening protocols employed in prior studies. It is important to acknowledge, however, that our reported prevalence of PFO may be underestimated due to potential underdiagnosis or underreporting in the NIS database, which is a known limitation associated with administrative data sources [17, 18]. A critical consideration when interpreting our findings is the potential underdiagnosis of PFOs among patients with PE in the comparison group. In our analysis, only 0.5% of PE hospitalizations were coded as having PFO, a markedly lower prevalence than expected in the general population. This discrepancy suggests that a substantial proportion of PFO carriers were misclassified as not having PFO, thereby diluting the apparent differences in clinical outcomes between the two groups.

Beyond its role in paradoxical embolism, a PFO may also have broader implications for patients at risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) [19]. A PFO constitutes a potential conduit for paradoxical embolization in the event of a PE - an inherently unpredictable event. Therefore, identifying and closing a PFO in individuals with known risk factors for VTE could, in theory, serve as a primary preventive measure to mitigate catastrophic embolic complications should a PE occur [19]. While this concept remains speculative and lacks randomized data, it underscores the importance of considering proactive PFO detection in select high-risk populations.

Routine screening for PFO among all patients presenting with acute PE remains controversial, largely due to a lack of clear evidence that universal screening improves clinical outcomes. Current guidelines, including the European Society of Cardiology, recommend a selective and symptom-driven approach [20, 21]. Although major US societies, including American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and the American Thoracic Society, provide detailed guidance on the management of acute PE, none specifically address whether or how to screen for or manage a concomitant PFO in PE patients, thereby underscoring the paucity of directed recommendations in this scenario and the need for individualized multidisciplinary decision-making. Our study identified a significant association between the presence of PFO and more severe clinical presentations among patients with acute PE; however, the precise nature of this relationship remains uncertain. It is unclear whether the presence of a PFO inherently places patients with PE at a higher clinical risk, possibly due to mechanisms such as paradoxical embolism and right-to-left shunting [22, 23], or whether this association was detected primarily because sicker patients were more likely to undergo comprehensive diagnostic evaluations, including echocardiography. Furthermore, pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale plausibly amplify the clinical impact of a PFO in acute PE by increasing right-to-left shunting duration and magnitude; however, these states are manifestations of PE severity rather than consequences of a PFO, and prior studies demonstrate a consistent increase in ischemic stroke with PFO but do not show a reproducible increase in hemodynamic severity per se [22, 24, 25]. Apparent associations between PFO and cor pulmonale/saddle PE in large administrative cohorts, such as in this study, may reflect ascertainment bias (sicker patients undergo echocardiography and PFO screening), underdetection of PFO in comparators, and residual confounding rather than a direct causal link. Therefore, our findings should be considered hypothesis-generating, and further prospective studies are needed to better delineate this relationship and inform optimal screening and management strategies.

Study limitations

This study has several important limitations. First, due to the administrative nature of the NIS, our findings rely on diagnostic and procedural codes, which are susceptible to coding errors, misclassification, and inaccuracies at the data collection sites, without the ability for independent adjudication or verification. Second, because the NIS records diagnoses at hospital discharge rather than upon admission, we cannot definitively determine whether PE was present on admission or developed subsequently during hospitalization. Third, the NIS lacks granular procedural details, such as the duration of catheter-directed interventions, the thrombolytic doses administered, the specific devices utilized, and the discharge medication regimens. Additionally, certain associations - such as the higher frequency of saddle pulmonary emboli and the lower prevalence of renal insufficiency or metastatic disease among PFO carriers - lack clear mechanistic explanations and likely reflect unmeasured confounding, a limitation inherent to administrative datasets that preclude detailed physiologic or imaging correlation. The observed co-occurrence of PFO with cor pulmonale/saddle PE should be interpreted cautiously, given verification bias (PFO sought in sicker patients), under-ascertainment of PFO in controls, and the absence of physiologic/imaging detail in administrative data needed to disentangle causality from severity confounding. Fourth, we were unable to assess long-term clinical outcomes, as the NIS database only includes inpatient hospitalization data. Fourth, the absence of detailed diagnostic imaging results and cardiac biomarkers in the NIS prevented us from accurately stratifying our patient population into the traditionally defined intermediate and high-risk PE categories. Finally, our study is limited by potential misclassification bias due to underdiagnosis of PFO in the NIS. Only 0.5% of patients hospitalized with PE were identified as having PFO, whereas the true prevalence in the general population approaches 25%. Consequently, many patients in the comparator group probably harbored an unrecognized PFO, which may have attenuated the differences in outcomes observed between groups. Similarly, among patients with a documented PFO, 95 had procedural codes indicating PFO closure; however, because of the NIS dataset’s structure, it is not possible to determine whether these closures occurred during the index hospitalization or before admission, which limits the ability to distinguish active from previously treated PFO cases.

Conclusion

In this large, nationwide analysis utilizing the NIS, we found that patients admitted with acute PE and concomitant PFO present with more severe clinical profiles, require increased utilization of advanced therapeutic interventions, and incur significantly greater healthcare resource utilization. While the presence of PFO was strongly associated with increased odds of stroke and peripheral embolism, there was no significant difference in adjusted in-hospital mortality. These findings highlight the importance of clinical vigilance for potential paradoxical embolic events in this patient subgroup. However, given the limitations inherent in administrative datasets, further prospective studies are necessary to confirm these associations and determine optimal screening and management strategies in patients with acute PE and suspected PFO.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. International Classification of Diseases Tenth Edition Codes (ICD-10) used to identify patients with acute PE and severity of illness.

Suppl 2. International Classification of Diseases Tenth Edition Codes (ICD-10) used to identify comorbidities.

Suppl 3. International Classification of Diseases Tenth Edition Codes (ICD-10) used to identify therapy for acute PE.

Suppl 4. International Classification of Diseases Tenth Edition Codes (ICD-10) used to identify outcomes.

Suppl 5. Baseline characteristics in PE patients with and without PFO.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

No relevant disclosures are reported by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Writing - original draft: AJ, SK, and MZ. Writing - reviewing and editing: MFN, RF, BON, PV, PEG, TF, HAD, MA, GG, HK, AA, and VA. Conceptualization and methodology: AJ, PV, PEG, TF, and VA. Data curation and formal analysis: AJ, SK, and AM. Resources and supervision: GG, HK, AA, and VA. Validation: PEG, TF, and HAD.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Konstantinides S, Geibel A, Kasper W, Olschewski M, Blumel L, Just H. Patent foramen ovale is an important predictor of adverse outcome in patients with major pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 1998;97(19):1946-1951.

doi pubmed - Ismayl M, Ismayl A, Hamadi D, Aboeata A, Goldsweig AM. Catheter-directed thrombolysis versus thrombectomy for submassive and massive pulmonary embolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2024;60:43-52.

doi pubmed - Vardar U, Attanasio S, Jolly N, Malhotra S, Doukky R, Vij A. Trends and disparities in patients with acute pulmonary embolism with and without cor pulmonale undergoing percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a national inpatient sample database study. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2023;53:S67.

doi - Ismayl M, Goldsweig AM. Editorial: Like a kid in a candy shop: Choosing the sweetest therapy for submassive pulmonary embolism. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2024;62:82-84.

doi pubmed - Rigatelli G, Dell'Avvocata F, Cardaioli P, Giordan M, Bernasconi M, Palu M. Shut that door: a man with contemporaneous multisite paradoxical embolization. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2009;10(2):125-127.

doi pubmed - Freund Y, Cohen-Aubart F, Bloom B. Acute pulmonary embolism: a review. JAMA. 2022;328(13):1336-1345.

doi pubmed - Lucas TO, Schaustz EB, Dos Reis IJR, Lopes CG, Mendoca VS, Salluh JIF, Zukowski CN, et al. Risk of ischemic stroke in patients with pulmonary embolism and patent foramen ovale: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2025;34(1):108157.

doi pubmed - Roy S, Le H, Balogun A, Caskey E, Tessitore T, Kota R, Hejirika J, et al. Risk of stroke in patients with patent foramen ovale who had pulmonary embolism. J Clin Med Res. 2020;12(3):190-199.

doi pubmed - Le Moigne E, Timsit S, Ben Salem D, Didier R, Jobic Y, Paleiron N, Le Mao R, et al. Patent foramen ovale and ischemic stroke in patients with pulmonary embolism: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):756-763.

doi pubmed - Sitwala P, Khalid MF, Khattak F, Bagai J, Bhogal S, Ladia V, Mukherjee D, et al. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale in patients with cryptogenic stroke - an updated comprehensive meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2019;20(8):687-694.

doi pubmed - Kwok CS, Alisiddiq Z, Will M, Schwarz K, Khoo C, Large A, Butler R, et al. The modified risk of paradoxical embolism score is associated with patent foramen ovale in patients with ischemic stroke: a nationwide US analysis. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2024;11(7).

doi pubmed - Zhang RS, Yuriditsky E, Zhang P, Truong HP, Xia Y, Maqsood MH, Greco AA, et al. Anticoagulation alone versus large-bore mechanical thrombectomy in acute intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2025;78:47-54.

doi pubmed - Raghupathy S, Barigidad AP, Doorgen R, Adak S, Malik RR, Parulekar G, Patel JJ, et al. Prevalence, trends, and outcomes of pulmonary embolism treated with mechanical and surgical thrombectomy from a nationwide inpatient sample. Clin Pract. 2022;12(2):204-214.

doi pubmed - Patel KN, Majmundar V, Majmundar M, Zala H, Doshi R, Patel V, Dani SS, et al. National trends, in-hospital mortality, and outcomes of atrial septal defect/patent foramen ovale closure procedure: an analysis from the national inpatient sample. Struct Heart. 2024;8(6):100323.

doi pubmed - HCUP-US NIS overview. Accessed July 9, 2025. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp.

- Lacut K, Le Moigne E, Couturaud F, Font C, Vazquez FJ, Canas I, Diaz-Peromingo JA, et al. Outcomes in patients with acute pulmonary embolism and patent foramen ovale: Findings from the RIETE registry. Thromb Res. 2021;202:59-66.

doi pubmed - Khera R, Angraal S, Couch T, Welsh JW, Nallamothu BK, Girotra S, Chan PS, et al. Adherence to methodological standards in research using the national inpatient sample. JAMA. 2017;318(20):2011-2018.

doi pubmed - Zghouzi M, Jabri A, Kumar S, Maligireddy A, Bista R, Paul TK, Nasser MF, et al. Association between frailty, use of advanced therapies, in-hospital outcomes, and 30-day readmission in elderly patients admitted with acute pulmonary embolism. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2025.

doi pubmed - Meier B. A cardiologist's perspective on patent foramen ovale-associated conditions. Cardiol Clin. 2024;42(4):547-557.

doi pubmed - Pristipino C, Germonpre P, Toni D, Sievert H, Meier B, D'Ascenzo F, Berti S, et al. European position paper on the management of patients with patent foramen ovale. Part II - Decompression sickness, migraine, arterial deoxygenation syndromes and select high-risk clinical conditions. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(16):1545-1553.

doi pubmed - Pristipino C, Sievert H, D'Ascenzo F, Louis Mas J, Meier B, Scacciatella P, Hildick-Smith D, et al. European position paper on the management of patients with patent foramen ovale. General approach and left circulation thromboembolism. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(38):3182-3195.

doi pubmed - Shah AH, Horlick EM, Kass M, Carroll JD, Krasuski RA. The pathophysiology of patent foramen ovale and its related complications. Am Heart J. 2024;277:76-92.

doi pubmed - Sharma VK, Teoh HL, Chan BP. Extracerebral paradoxical embolisms in patients with intracardiac shunts. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2008;9(3):190-191.

doi pubmed - Elgendy AY, Saver JL, Amin Z, Boudoulas KD, Carroll JD, Elgendy IY, Grunwald IQ, et al. Proposal for updated nomenclature and classification of potential causative mechanism in patent foramen ovale-associated stroke. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(7):878-886.

doi pubmed - Hirsh JD, Burt JN, Panchal RM, Endler GT, Devalla RN, Mitchell ME, Villalobos MA. Saddle pulmonary embolus and simultaneous common carotid and subclavian artery emboli. Am Surg. 2023;89(9):3908-3910.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cardiology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.