| Cardiology Research, ISSN 1923-2829 print, 1923-2837 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cardiol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 16, Number 6, December 2025, pages 518-524

Preliminary Observations on Discordance Between Coronary Artery Calcium Score of Zero and Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography Findings in Asymptomatic Adults

Farhan Ashrafa, b , Mohammad Raza Qureshia, Masoud Alama, Sushma Umroaa, Shafaath Husaina, Faiz Ul Amina, Munir Khana

aLife Core Private Clinic, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

bCorresponding Author: Farhan Ashraf, Life Core Private Clinic, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Manuscript submitted October 15, 2025, accepted November 21, 2025, published online December 20, 2025

Short title: Unmasking Non-Calcified Plaque: CAC vs. CCTA

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cr2151

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring is widely used to screen for coronary artery disease (CAD) in asymptomatic individuals. However, it detects calcified plaques and may miss non-calcified or soft plaques. This study compared the diagnostic accuracy of CAC scoring with coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) for detecting CAD in asymptomatic individuals with risk factors.

Methods: Eighteen asymptomatic adults with a CAC score of 0 underwent CCTA to evaluate for subclinical CAD. Clinical, biochemical, and lifestyle risk factors were assessed. Diagnostic agreement between CAC and CCTA was analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Results: The cohort had a mean age of 51.4 ± 10.6 years, 88.8% were male, and mean body mass index (BMI) was 27.7 ± 3.6 kg/m2. Smoking (70.5%) and family history of CAD (56.25%) were prevalent. Biochemical analyses showed preserved renal function and non-diabetic glycemic profiles. Despite the absence of calcification on CAC, CCTA revealed CAD in 72.2% (13/18) of participants, detecting non-calcified plaques missed by CAC scoring. Elevated cardiac and inflammatory markers, including high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T, apolipoprotein B (apoB), and lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)), were observed in those with positive CCTA findings. The Wilcoxon signed rank test indicated a significant difference between the modalities (Z = -3.606, P < 0.001).

Conclusions: CCTA detected non-calcified atherosclerosis missed by CAC and demonstrated superior sensitivity for early CAD detection in asymptomatic individuals.

Keywords: Coronary artery disease; Coronary artery calcium scoring; Coronary computed tomography angiography; Wilcoxon signed rank test; Specificity; Sensitivity

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Ischemic heart disease is well known to be the most common cause of death worldwide [1]. Screening strategies for coronary artery disease (CAD) have included electrocardiography (ECG) stress test, single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), dobutamine stress echo, which reveal reversible stress-induced ischemia, but not necessarily the direct assessment of extent of CAD. The introduction of coronary computed tomography (CT) calcium score (coronary artery calcium (CAC)) did indirectly introduce a way to quantify extent of CAD in asymptomatic individuals [2]. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) trail identified CAC scoring as a major cardiovascular risk stratification tool, showing patients with elevated CAC score had adverse outcomes independent of traditional risk factors. A 2015 study also showed power of calcium score of 0 in predicting 15-year mortality rate [3]. However, CAC is unable to pick up on non-calcified/soft plaques. Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) can pick up non-calcified disease but currently is being used only in symptomatic individuals based on guidelines [4]. We propose that in asymptomatic individuals deemed medium to high risk for CAD, screening with CCTA instead of calcium score could potentially be beneficial, both for early detection of disease, and to tailor treatment strategy based on severity of disease [5]. We examined the relationship between CAC scores of 0 and CCTA findings in asymptomatic adults with cardiovascular risk factors. The aim of this study was to describe the extent of discordance between the two imaging modalities in detecting CAD.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design and population

This study was designed as an exploratory analysis. The study was carried out at the Department of Cardiology, at an outpatient facility in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. This was a retrospective, cross-sectional, clinic-based study. Patients visited the facility for primary prevention/secondary prevention/wellness checks. All patients underwent CAC score and CCTA. Only asymptomatic patients with CAC score of 0 were selected for this study.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with calcium score of 0, and two or more traditional risk factors for CAD (smoking, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, age, family history) were included.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with previous coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, previous coronary stent placement, dialysis-dependent renal failure, and incomplete demographic and laboratory data were excluded.

All the patients meeting the inclusion criteria undergoing both CCTA and CAC between October 2022 and October 2024 were included in the study. A total of 18 patients met the above criteria. Scans for the procedures had been acquired on a computerized tomography scanner using cardiac gating. Renal function was checked before and after the scan. Patients were monitored for any acute allergic reaction. All scans were interpreted by a level 3 cardiac CT-trained cardiologist, and the results were documented.

Data collection and variables

Each participant underwent a detailed clinical assessment, including collection of demographic data (age, gender) and lifestyle factors, such as smoking status, alcohol consumption, sleep apnea diagnosis, and obesity status (defined by body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2). Demographic information, medical history, and health-related behaviors were recorded using a self-administered questionnaire with the help of a trained employee. Demographic and blood pressure data were also recorded by a trained nurse.

Additionally, comprehensive laboratory tests were performed, including but not limited to: lipid profile: low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), triglycerides, apolipoprotein B (apoB), lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)); renal function markers: creatinine, urea, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR); inflammatory and cardiac markers: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; endocrine/metabolic markers: glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO), uric acid; immunological markers: CD25, CD28; hematological marker: red blood cell distribution width-coefficient of variation (RDW-CV); homocysteine.

Diagnostic imaging

All participants first underwent CAC scoring using a non-contrast CT scan. Scores were calculated using the Agatston method. Subsequently, CCTA was performed using a dual source multidetector CT scanner following administration of iodinated contrast. Images were analyzed for the presence and severity of coronary artery stenosis. The patients with an initial heart rate greater than 80 beats per minute (bpm) received an intravenous (IV) dose of beta-blocker (5 mg metoprolol), approximately 10 min before imaging. An ECG-gated multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) scan was performed using a 384-slice scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Forchheim, Germany) without IV contrast injection to quantify CAC. Then, CCTA was performed by IV contrast agent injection (using 65 mL of 400 mg I/mL contrast material infused at 4 mL/s followed by a 50-mL saline flush). Before the scan, 0.4 mg of nitroglycerin spray was administered. On average, patients received a radiation dose of 4 mSv. None of the patients experienced any adverse events from contrast administration. CCTA images were interpreted by a level 3 cardiac CT-trained cardiologist. CAC was calculated using the method described before and was divided into the five following stages: no calcification (0), minimal calcification (1 - 10), mild calcification (11 - 99), moderate calcification (101 - 300), and extensive calcification (> 300) [6]. Moreover, the severity of coronary artery atherosclerosis was classified into four categories, namely minimal stenosis (< 25% diameter reduction), mild stenosis (25-49% diameter reduction), moderate stenosis (50-69% diameter reduction), and severe stenosis (> 70% diameter reduction) [7].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated to evaluate the diagnostic performance of CAC score (0) in predicting stenosis detected by CCTA. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed to compare paired diagnostic results (CAC = 0 vs. CCTA findings). All statistical analyses were performed using Excel and SPSS software. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee and adhered to relevant ethical guidelines.

| Results | ▴Top |

Demographic characteristics

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Median age was 51.4 ± 10.6 years, and most participants were male.

Click to view | Table 1. Basic Demographic Information of the Participants |

Lifestyle factors and medical history

Common risk factors included smoking and a family history of CAD (Table 2). About 47.05% of the patients had a history of sleep apnea, and 41.17% reported hypertension. No participants reported history of kidney or autoimmune disease (Table 3). Participants had a median body fat percentage of 32.9%, with an interquartile range of 23.8-39.2%.

Click to view | Table 2. Lifestyle Factors Information of the Participants |

Click to view | Table 3. Medical History of the Participants |

Biochemical and clinical characteristics

The biochemical profile of the study participants is summarized in Table 4. The mean serum creatinine was 1.16 ± 0.5 mg/dL, while the mean urea level was 9.36 ± 2.70 mmol/L. The eGFR averaged 115 ± 14.34 mL/min, indicating preserved renal function across the cohort.

Click to view | Table 4. Biochemical Markers |

Coronary CT findings

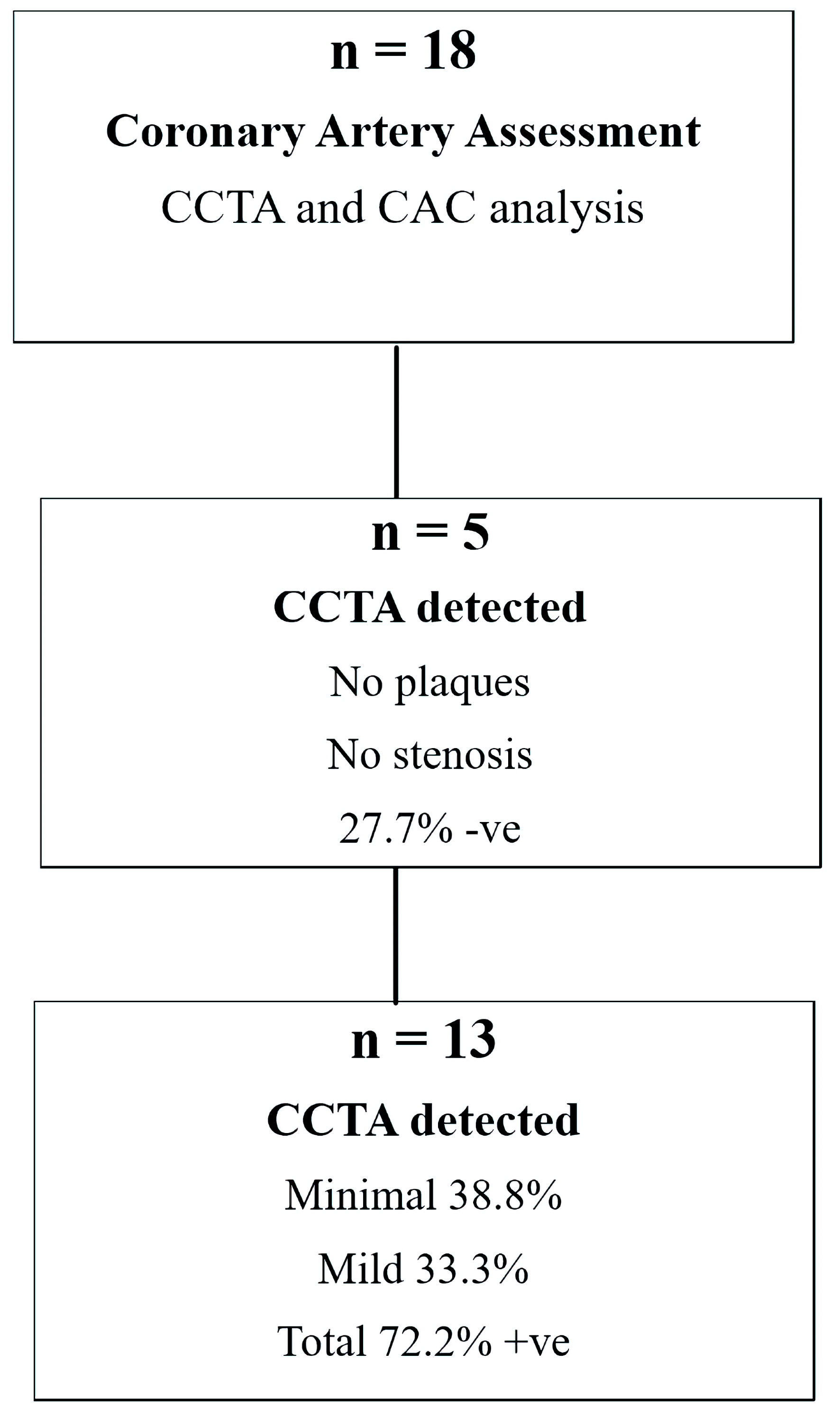

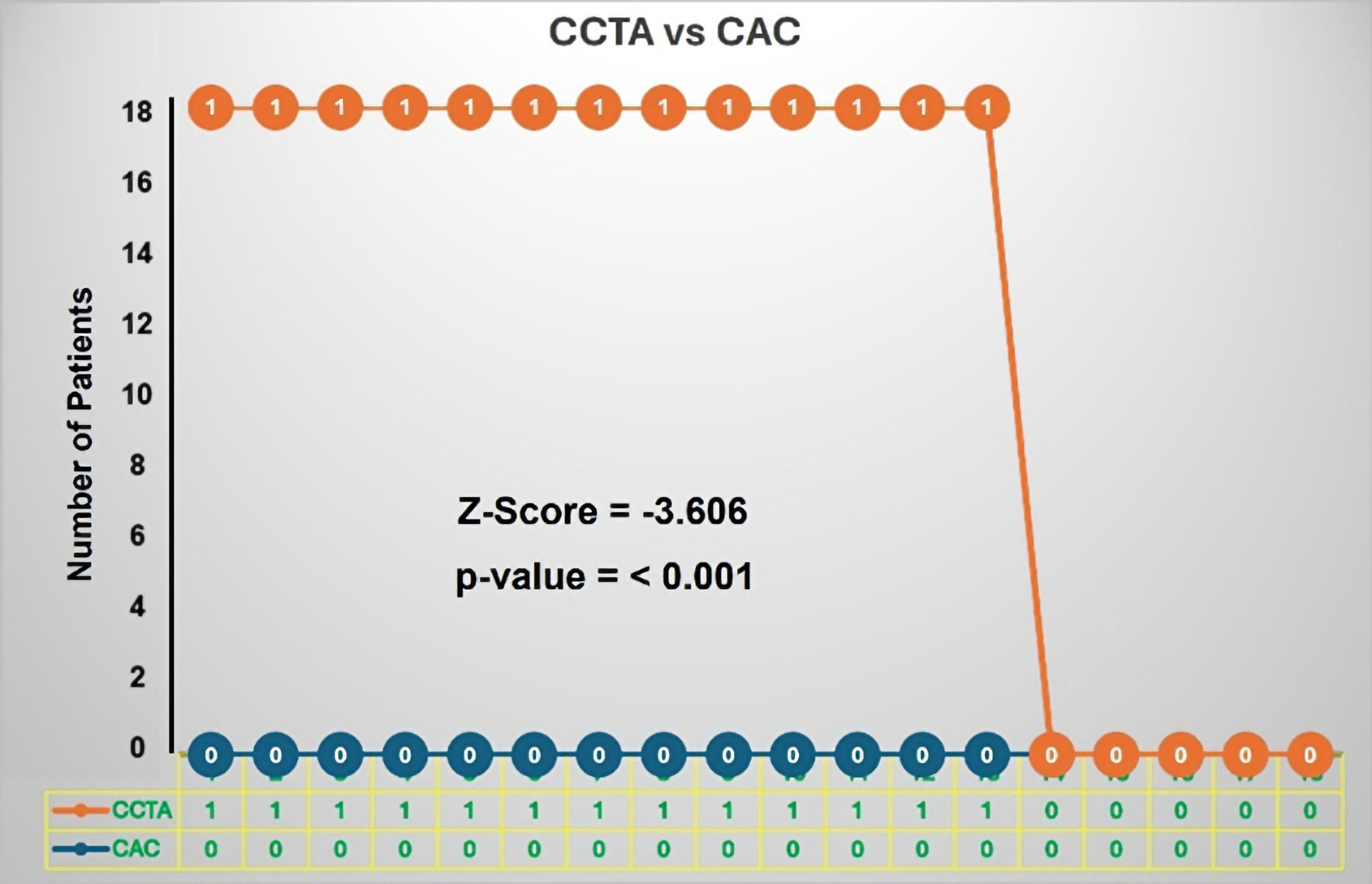

All 18 participants had a CAC score of 0, suggesting absence of calcified coronary plaques. CCTA identified non-calcified plaques indicative of CAD in 13 of these 18 participants (72.2%), classifying them as false negatives (FNs) by CAC (Fig. 1). A Wilcoxon signed rank test confirmed a statistically significant difference between CAC scoring and CCTA findings (Z = -3.606, P < 0.001), highlighting that CCTA consistently identified more cases of CAD that were missed by CAC scoring (Fig. 2). No adverse reactions to contrast were observed. There were no allergic responses or cases of contrast-induced nephropathy, and renal function remained stable after the scan.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Coronary artery assessment based on CCTA findings in the study population (n = 18). Positive CCTA results were observed in 13 patients (72.2%), including minimal stenosis in 38.8% and mild stenosis in 33.3%. Negative findings were present in five patients (27.7%), with no plaques or stenosis detected. CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography; +ve: positive; -ve: negative. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. The diagnostic comparison between CAC scoring and CCTA in 18 asymptomatic individuals. All patients had a CAC score of 0, suggesting no coronary artery disease. However, subsequent CCTA revealed that 13 out of 18 individuals had significant coronary artery disease. A Wilcoxon signed rank test demonstrated statistically significant difference between the two diagnostic modalities (Z = -3.606, P < 0.001). CAC: coronary artery calcium; CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography. |

Diagnostic performance of CAC

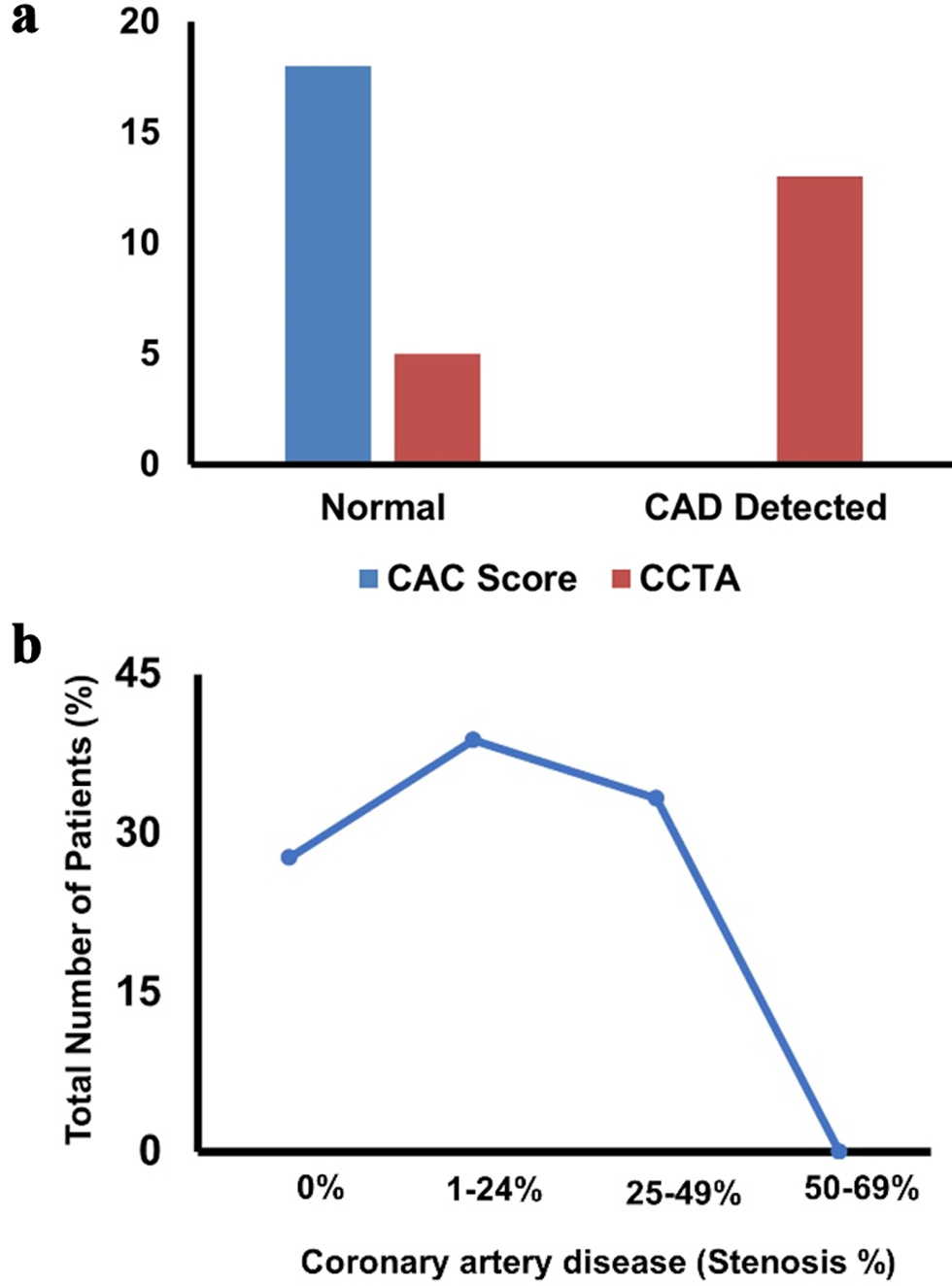

When compared to the reference standard CCTA, five patients were confirmed to have no CAD (true negatives (TN)), 13 patients were found to have non-calcified plaques that were missed by CAC (FNs).

Extent of CAD is shown in Table 5 and Figure 3b. The PPV and NPV for CAC score in identifying CAD were calculated. CAC score showed poor concordance with CCTA findings, with a high rate of false-negative results (72.2%), highlighting its limitations in detecting non-calcified CAD. The details are given in Figure 3a.

Click to view | Table 5. Distribution of Different Coronary Artery Disease (Stenosis %) Subgroups in Relation to the Total Number of Patients % |

Click for large image | Figure 3. (a) Bar chart showing the comparison of CAC score and CCTA in detecting CAD. (b) Curve showing the percentage of patients with stenosis. CAC: coronary artery calcium; CAD: coronary artery disease; CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography. |

Wilcoxon signed rank test

The Wilcoxon signed rank test revealed a statistically significant difference between CAC score and CCTA findings in detecting CAD, with a Z-score of -3.606 and an associated P value of < 0.001. Specifically, 1) Z-score = -3.606 - A large negative Z-value suggests that CCTA detects significantly more cases than the CAC score. The negative sign reflects the ranking direction but does not affect the interpretation; 2) P value (asymptotic significance, two-tailed) < 0.001 - Since P < 0.05, the difference between CCTA and CAC Score is statistically significant. This confirms that CCTA results are systematically higher than CAC score results rather than differing by chance).

Post hoc power analysis

A post hoc power analysis was conducted to assess the statistical power of the Wilcoxon signed rank test comparing CAC scoring and CCTA results. Using the observed test statistic (Z = -3.606) from a sample of 18 participants, the effect size (r) was calculated as:

This corresponds to an estimated Cohen’s d of approximately 1.70, indicating a large effect. Using this effect size, a two-tailed paired sample power analysis at α = 0.05 revealed a statistical power of > 99.9% (power = 0.9999). This post hoc power estimation suggested that the observed difference would likely be detectable in a larger sample, supporting the reliability of the observed effect.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines have recommended CAC for CAD screening in intermediate risk individuals [3]. While this allows detection of calcified disease, it is unable to detect non-calcified disease, or soft plaques. Considering the burden of CAD and the fact that ischemic heart disease is the number one cause of death worldwide, missing out on soft plaque can be detrimental. A previous study in 2008 where asymptomatic individual underwent CCTA showed only 4% of people had non-calcified plaque [8]. In our study, 72% of the population had soft plaque, indicating CAD that would be missed by using CAC alone. This exploratory study highlights a discrepancy between CAC scoring and CCTA findings in asymptomatic adults with cardiovascular risk factors, with CCTA identifying non-calcified plaque in majority of the participants. This study included only 18 participants, which restricts generalizability. The observed 72% prevalence of non-calcified plaque should be interpreted cautiously, as smaller samples are more prone to random variation.

Despite the small sample size, the observed diagnostic discrepancy between CAC scoring and CCTA reached statistical significance (Wilcoxon signed rank test, Z = -3.606, P < 0.001). To assess the robustness of this finding, a post hoc power analysis was performed, revealing an effect size (Cohen’s d) of 1.70 and a power exceeding 99.9% (α = 0.05). These results suggest a statistically robust difference between CAC and CCTA findings, although the small sample and exploratory nature of the study warrant cautious interpretation.

Previous studies have mentioned soft plaque being detected in individuals with CAC of 0. An Austrian study revealed that in individual with calcium score of 0, 32% had soft plaque on CCTA [9]. Our study further highlights the importance of CCTA for detection of non-calcified plaque, and the degree of stenosis in coronaries. This not only helps in truly detecting CAD but also helps in managing patient care with reference to appropriate LDL targets [5]. In our study, 65% of participants were Caucasian/Middle Eastern, while about 30% of the study participants were South Asian, possibly suggesting high risk of developing soft plaque in this population, and warrants further study.

Individuals in our study with soft plaque had mild or minimal CAD, indicating need of medical therapy initiation. Using CAC by itself would have failed to identify these individuals for appropriate medical therapy. After identification of CAD, these patients were started on antiplatelet and statin therapy, with a focus on reaching target LDL based on guidelines and degree of stenosis. Using CCTA for CAD screening also aligns with the ongoing discussion of using CCTA-derived plaque volume for CAD staging and treatment [10, 11]. CCTA also has the potential to better risk-stratify patients with elevated CAC scores, as the same principle of missing soft plaque applies.

Screening for CAD should be more aggressive, and accurate, since it is the number one cause of mortality worldwide. CAC will miss individuals with CAD that only have soft plaque. CCTA can provide this information accurately in people with risk factors. Although our study population is limited by small sample size, it highlights the potential value of CCTA in CAD screening in asymptomatic individuals with risk factors. Larger study pools, like the ongoing SCOT-HEART 2 trial, are required to help push this point further in the future [12].

While our study focused on individuals with a CAC score of 0, the broader limitations of CAC scoring are worth noting. Even in patients with mild or moderate calcification, the calcium score does not reflect overall plaque burden or the degree of luminal narrowing. Some individuals with low or moderate calcium scores may still have significant stenosis, which can be identified by CCTA but not by CAC scoring. This is increasingly recognized in clinical practice and has contributed to a shift toward more comprehensive CT-based evaluation. Advances in CCTA, including CT-derived fractional flow reserve and developments in plaque characterization, further widen the gap between CAC and CCTA. These techniques provide both functional and structural information, which improves risk assessment and helps guide management. Although our study did not use these advanced tools, acknowledging their role helps place our findings in the context of current imaging capabilities.

Larger studies will also help understand the cost implications of using CCTA for CAD screening. While CCTA costs more than CAC score, detecting CAD at earlier stage can potentially cut down future costs related to advanced CAD management and its complications, such as myocardial infarction and ischemic heart failure. Advances in CT technology, including dose-reduction algorithms, prospective ECG gating, and iterative reconstruction, have significantly lowered radiation exposure associated with CCTA. These developments improve the feasibility and safety of incorporating CCTA into screening or preventive cardiology strategies in the future.

Limitations

This is a single-center study. Our study was conducted at an outpatient facility, where the volume is lower than a typical in-patient facility. To meet the inclusion criteria, most scans performed at our facility could not be used, since these scans had a calcium score greater than 0. This led to small patient population for this study. Most patients in our study were male, the low female population in our study does introduce potential bias. The data were obtained retrospectively; unmeasured confounders could not be fully excluded. Future studies with larger, prospectively designed cohorts and balanced gender representation are warranted to validate and expand upon these observations.

Conclusions

In individuals who have risk factors for CAD, CAC can miss CAD in the form of soft plaque. CCTA appears to be a more comprehensive option for CAD screening in such individuals; however, larger patient pools are required for further validation.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

This is a retrospective study using deidentified data; therefore, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) did not require consent from the patients.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Dr. Faiz Ul Amin and Dr. Farhan Ashraf. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Dr. Farhan Ashraf and Dr. Faiz Ul Amin. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript, read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; BMI: body mass index; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; HOMA-IR: homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance; CAC: coronary artery calcium; CAD: coronary artery disease; CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography; apoB: apolipoprotein B; Lp(a): lipoprotein(a); eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; CD: cluster of differentiation; anti-TPO: anti-thyroid peroxidase; RDW-CV: red blood cell distribution width-coefficient of variation; VO2 max: maximal oxygen consumption

| References | ▴Top |

- Wang Y, Li Q, Bi L, Wang B, Lv T, Zhang P. Global trends in the burden of ischemic heart disease based on the global burden of disease study 2021: the role of metabolic risk factors. BMC Public Health. 2025;25(1):310.

doi pubmed - Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(10):1376-1414.

doi pubmed - Valenti V, B OH, Heo R, Cho I, Schulman-Marcus J, Gransar H, Truong QA, et al. A 15-year warranty period for asymptomatic individuals without coronary artery calcium: a prospective follow-up of 9,715 individuals. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(8):900-909.

doi pubmed - Writing Committee M, Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, Amsterdam E, Bhatt DL, Birtcher KK, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(22):e187-e285.

doi pubmed - Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, Chapman MJ, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(1):111-188.

doi pubmed - Hecht HS, Cronin P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, Kazerooni EA, Narula J, Yankelevitz D, et al. 2016 SCCT/STR guidelines for coronary artery calcium scoring of noncontrast noncardiac chest CT scans: A report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and Society of Thoracic Radiology. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2017;11(1):74-84.

doi pubmed - Cury RC, Leipsic J, Abbara S, Achenbach S, Berman D, Bittencourt M, Budoff M, et al. CAD-RADS 2.0 - 2022 Coronary Artery Disease - Reporting and Data System An Expert Consensus Document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American College of Radiology (ACR) and the North America Society of Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI). Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2022;4(5):e220183.

doi pubmed - Choi EK, Choi SI, Rivera JJ, Nasir K, Chang SA, Chun EJ, Kim HK, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography as a screening tool for the detection of occult coronary artery disease in asymptomatic individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(5):357-365.

doi pubmed - Plank F, Friedrich G, Dichtl W, Klauser A, Jaschke W, Franz WM, Feuchtner G. The diagnostic and prognostic value of coronary CT angiography in asymptomatic high-risk patients: a cohort study. Open Heart. 2014;1(1):e000096.

doi pubmed - Min JK, Chang HJ, Andreini D, Pontone G, Guglielmo M, Bax JJ, Knaapen P, et al. Coronary CTA plaque volume severity stages according to invasive coronary angiography and FFR. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2022;16(5):415-422.

doi pubmed - Freeman AM, Raman SV, Aggarwal M, Maron DJ, Bhatt DL, Parwani P, Osborne J, et al. Integrating coronary atherosclerosis burden and progression with coronary artery disease risk factors to guide therapeutic decision making. Am J Med. 2023;136(3):260-269.e267.

doi pubmed - McDermott M, Meah MN, Khaing P, Wang KL, Ramsay J, Scott G, Rickman H, et al. Rationale and design of SCOT-HEART 2 trial: CT angiography for the prevention of myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2024;17(9):1101-1112.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cardiology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.